Originally a term which was applied to a division of the French military, the avant-garde was a group of specially trained soldiers who performed reconnaissance operations; and advanced prior to the main party of the attacking force.

Within the context of modern art, the avant-garde, as described by the Oxford Dictionary of 20th Century Art (Chilvers,1998, p.42) is used as a relatively broad term:

‘…applied to any group, particularly of artists that considers itself innovative and ahead of the majority; as an adjective, the word is applied to work characteristic of such groups.’

However, the term avant-garde is not one which is only used to describe artists, works of art and art movements; it can also describe political beliefs which have similar properties or indeed any thought or reasoning within a specific field which falls under the definition given by Chilvers earlier in the text.

Of the many avant-garde movements throughout history, it is Futurism which will here be analysed in terms of its classification as an avant-garde movement. The influence which it gave artists such as Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla will also be briefly discussed. A connection between Futurist ideologies and contemporary modern science will also be attempted. First however, the origins of Futurism must be briefly outlined.

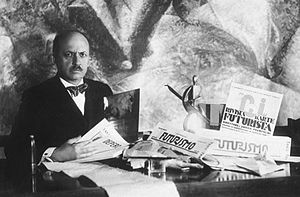

Marienetti

In his text, The Shock of the New, Robert Hughes establishes that Futurism was founded and officially launched as a movement on the 20th of February 1909 in the Paris newspaper Le Figaro (Hughes, 1991, p.43) by Fillipo Tommaso Marinetti. This text, which appeared on the front page of the newspaper, nonetheless; was the first Futurist Manifesto.

Despite being published in the French language, it launched the Italian political and literary movement of Futurism. Reasoning for Marinetti’s choice to launch the movement in Paris is given by Jane Rye in her text Futurism (1972, p.14); ‘…a movement launched there would inevitably attract attention everywhere it was wanted.’

Rye (1972, p.11) also outlines the fundamental beliefs which were contained within the Futurist Manifesto as

‘… the exaltation of speed, youth and action; of violence and conflict; rebellion against the past and disgust with the stagnation of Italian culture; a passionate enthusiasm for the beauties of the industrial age.’

The spread of these futurist ideas is reinforced by Hughes (1991, p.40) where he cites Marinetti as ‘… the first international agent-provocateur of modern art.’ Hughes goes on to remark that the Marinetti’s ideas were a significant influence on avant-garde movements throughout Europe, influencing groups as wide as the Constructivists in Russia.

Support for the fact that Futurist ideals were avant-garde in their very nature is reinforced shortly thereafter by Hughes (1991, p.42) in which he claims ‘Marinetti’s enemy was the past. He attacked history and memory…’ This argument falls straight into the definition of the avant-garde given by Chilvers (1998, p.42). Marinetti’s writings; as reproduced in Futurist Manifestoes, (1973, (trans) Brain R., et al., (ed) Apollonio, U., p.21) ordered a destruction of the past in order to embrace the new technologies of the time:

‘… Why should we look back, … Time and space died yesterday. … we have created eternal omnipresent speed. … We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, we will fight moralism…’

Hughes (1991, p.43) raises concern for the Artists whom agreed with Marinetti’s ideals with regards of ‘… how to translate this kind of vision into paint.’ Hughes then goes on to provide different techniques in which this could have been done; he first suggests stippling which was employed by Umberto Boccioni in pieces such as The City Rises. (1910, Oil on Canvas, 6ft 6.5ins x 9ft 10.5 inches, The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

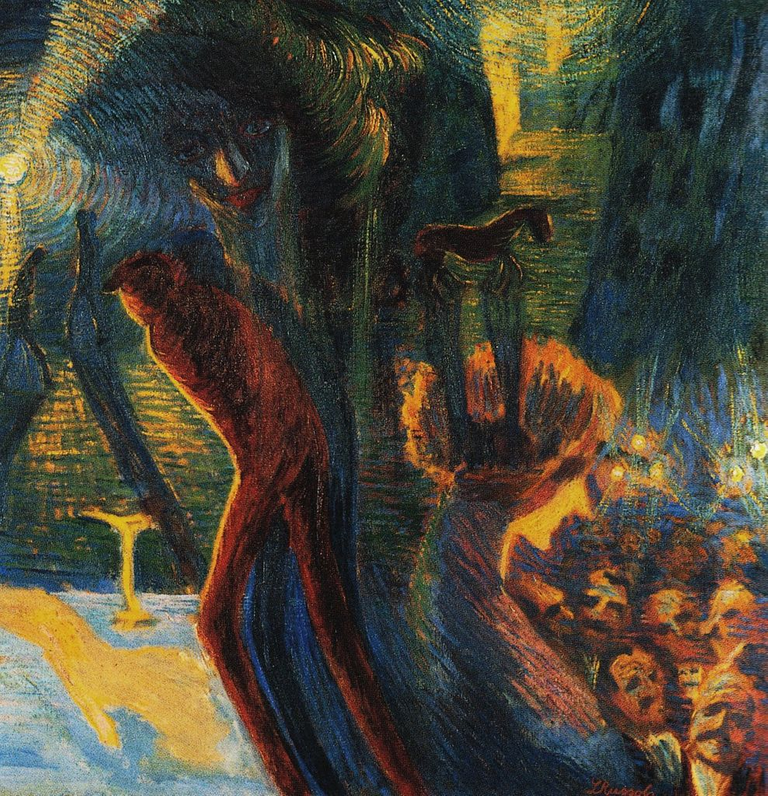

Stippling is also used in other works by key futurist artists. As stippling is a result of neo-impressionism, (Hughes, 1991, p.43) Work created in this style therefore caries a somewhat impressionistic residue, as can be seen in Luigi Russolo’s work Memories of a Night (1911, Oil on Canvas, 39.75 x 39.75 inches, Private Collection, New York)

Luigi Russolo’s work Memories of a Night (1911, Oil on Canvas, 39.75 x 39.75 inches, Private Collection, New York)

Luigi Russolo’s work Memories of a Night (1911, Oil on Canvas, 39.75 x 39.75 inches, Private Collection, New York) Other techniques or methods which Hughes suggests as being an influence on artists whom attempted to express Marinetti’s vision are those of Chronophotography as executed by Eadweard Muybridge in the 1880s; and also the newly discovered x-ray; with a combination of this and cubist style paintings, Giacomo Balla created works which Hughes (1991, p.44) claims are ‘… literal transcriptions of these photographs.’

This can be seen in Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912, Oil on Canvas, 35.5 x 43.5 inches, Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo) In which a dog and its owner are depicted, the ground a blur, with multiple impressions of the dog, its leash, and its owner in various states of movement and opacity are presented to the viewer.

This creates a somewhat fluid and blurred image; however it is one which fulfils most of the objectives of the Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto, (Boccioni, U., et al. 1910) reproduced in Futurist Manifestoes (1972, p.30), most notably the declaration; ‘That movement and light destroy the materiality of bodies.’

However, it can be argued that this piece is in contradiction with another of the main declarations of the same technical manifesto, which states that ‘… all forms of imitation must be despised…’ This can be seen as a drawback to this particular piece by Balla, however in every other way it fulfils the definition of a Futurist painting as laid out by the technical manifesto.

A source of influence for the Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto could be seen to be something as possibly far-fetched from the world of art as the world of science. During the modernist era, science was also going through a revolution of sorts. Albert Einstein’s discovery of relativity and the development of Quantum Mechanics changed human understanding of the nature of the universe.

Quantum Mechanics is a branch of Physics which deals with the measurement of energy at an atomic level; and the seemingly random nature of photons, electrons and other sub-atomic particles under certain conditions. Quantum mechanics deals with the discovery of the fourth dimension within perceivable space, time.

The Quantum takes into account all possible variables, and as in the entry on Quantum Mechanics in The Grolier Family Encyclopaedia (1995) it is stated that ‘… only predictions of the probability of various behaviours can be made.’

This can be seen in Futurist paintings, however, it is arguable that they are only able to display a finite number of these possibilities; otherwise an infinitely large canvas with infinite volumes of paint would be required in order to represent every possibility. However; from a subjective point of view, it can be argued that Futurist works such as Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash represent all that is needed for human comprehension of such a complex scientific theorem.

Within such a short text, it is impossible to address this issue any further or in any exhaustive depth: however before leaving this idea, it must be noted that this connection between the theories of contemporary physics of the time; and Futurist painting is made by Sigfried Giedion; as acknowledged by Arthur P. Molella in his article in the journal Technology and Culture, entitled: Science Moderne: Sigfried Giedion's Space: Time and Architecture and Mechanization Takes Command (2002, p. 383). Molella argues: ‘the futurist movement nevertheless guided Giedion’s thinking about the complementarities of modern physics and abstract art.’ Support for this can be seen once more in Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, despits it not being completely abstract in a literal sense.

The Futurists were avant-garde in every context of the word; their influence could have possibly been derived from contemporary physics and science. Marinetti’s ideologies were avant-garde, and the artists whom surrounded him; such as Russolo, Balla and Boccioni attempted to translate his vision into works of art; with influence taken from neo-impressionism, chronophotography and contemporary physics and scientific theories.

Their love of the machine and of an advanced future is heavily reinforced by their many writings. The Futurists believed that art would be able to, aspire to certain greatness; by disregarding all that was done before in the field; not dissimilar to the replacement by science of Newtonian mechanics with that of the quantum.