Public Interest Considerations

If the above weight of authority were not already an insurmountable

obstacle to the Respondents' applications to stay these proceedings,

the bar rises further still due to three important public interest

considerations:there is a substantial public interest in the proceedings,

including as private enforcement of Part IV of the CCA[1];that the public interest in Part IV enforcement is enhanced by

the proceedings being representative proceedings[2];the private, civil enforcement of Division 1 - Cartel Conduct of

Part IV of the CCA is a preliminary step in public enforcement

of the criminal prohibitions on cartel conduct (CCA ss 45AF and

45AG).

These proceedings also satisfy the public interest of aiding in the

development of the law generally[3]. In particular the proceedings

involve:the first application for a No Adverse Cost Order under s 84(2)

of the CCA;likely the first judicial examination of the new concerted

conduct provisions in s45(1(c) of the CCA[4];likely the first judicial consideration of the provisions

previously known as s4D exclusionary provisions since their move

into Division 1 - Cartel Conduct of Part IV of the CCA[5]; andthe first application of market based causation to

cryptocurrency markets[6].

The comments of Brennan J in Jago are apt to these proceedings due

to the above considerations.

"Moreover, although our system of litigation adopts the adversary

method in both the criminal and civil jurisdiction, interests other

than those of the litigants are involved in litigation, especially

criminal litigation. The community has an immediate interest in the

administration of criminal justice to guarantee peace and order in

society. The victims of crime, who are not ordinarily parties to

prosecutions on indictment and whose interests have generally gone

unacknowledged until recent times, must be able to see that justice is

done if they are not to be driven to self-help to rectify their

grievances. ...And it is likely to engender a festering sense of injustice on the

part of the community and the victim. The reasons for granting stay

orders, which are as good as certificates of immunity, would be

difficult of explanation for they would be largely discretionary. If

permanent stay orders were to become commonplace, it would not be long

before courts would forfeit public confidence. The granting of orders

for permanent stays would inspire cynicism, if not suspicion, in the

public mind."[7]

In Epic, the Full Court examined in detail the public policy

reasons for refusing to grant a stay of proceedings, which, as in

these proceedings:involve alleged breaches of Part IV of the the CCA[8];

which "has, and is continuing to, adversely affect the state of

competition in markets in Australia and very large numbers of

Australians"[9];which presents important opportunities for clarifying the

law[10], as noted above;which involves the Second Respondent, both as intervener in that

appeal and as the respondent in very similar Part IV proceedings

by Epic Games, Inc.[11]

In Epic those reasons were strong enough to over-ride "a

contractual agreement with Apple to litigate in the Northern

District of California"[12] and where there were proceedings in

that jurisdiction which had already been heard[13] and thus there

was no risk of stultification of proceedings.In Epic the Full Court concluded that "having regard to the issues

in this proceeding, and the impact a determination by this Court

will have on consumers in Australia, this is a very strong policy

consideration that favours denying a stay of this proceeding."[14]The Applicant submits that the public policy considerations in these

proceedings are as strong or even stronger than in Epic.The level of harm to Australian consumers caused by the alleged

breaches is arguably greater in these proceedings than in Epic.

Not being able to download apps to your iPhone from non-Apple

sources and indirectly paying the cost of the 30% commission Apple

charges developers[15] is a substantial detriment to consumers.But not even hearing about, or not being able to obtain critical

information about a new industry using new technology

(blockchain/cryptocurrency) that seeks to revolutionise both finance

and the internet and provide great consumer benefit is even worse.

The delay in the development of the cryptocurrency industry caused

by the Respondents' ad ban also prevented consumers receiving these

benefits earlier.Moreover the direct financial harm to the value of investments in

cryptocurrency of millions of Australian consumers[16] is arguably

orders of magnitude larger than the pass through costs to millions

of Australian consumers of allegedly excessively high app store

commissions on small retail transactions via apps. The size of an

individual consumer actual or potential investment in cryptocurrency

is typically many orders of magnitude larger ($100s to $millions)

than spending on apps and in-app purchases (tens or hundreds of

dollars).Cartel conduct is also the most serious and damaging type of

anti-competitive conduct prohibited by Part IV and this is

recognised by the criminal sanctions in ss 45AF and 45AG. Thus the

public interest is even greater than in enforcement of non-criminal

Part IV provisions such as in Epic.These proceedings involve more opportunities to clarify the

operation of the law (as outlined above) than Epic.Finally, as a class action, if successful, these proceedings will

provide direct financial compensation to millions of consumers

harmed by the Respondents conduct, whereas in Epic the broad

consumer benefit is both indirect and forward looking. It will not

compensate consumers for damage suffered in the past.Moreover, unlike Epic, if the Respondents' applications to stay

proceedings, either permanently, or until further order, were

granted it would lead to a stultification of these important public

interest proceedings enforcing Part IV of the CCA.There are no other viable mechanisms for enforcing Part IV of the

CCA against the Respondents.The ACCC has not commenced or even foreshadowed enforcement or

investigatory action, despite numerous notifications by the

Applicant[17], the ACCC[']{dir="rtl"}s ongoing enquiries into the

application of Part IV to the Respondents[18] and the establishment

of a prima facie case in these proceedings.Traditional litigation funding firms have been unwilling to fund

these proceedings[19], despite it having a very high value book

build[20] and the establishment of a prima facie case.The considerations of Brennan J above are particularly relevant

given the characteristics of the Respondents which:are among the most powerful and wealthy companies in the

world[21];control crucial channels of communications and information flows

relied upon by the public, businesses and governments

alike[22];have exercised their power to influence political, legislative

and regulatory processes in their favour, de-platform entire

industries and become the arbiters of acceptable speech.

These combination of factors represent power, wealth and influence

on a scale never before held by corporations and surpassing that of

many nation states. Moreover the processes by which they wield this

power lacks any of the checks and balances by which sovereign

democratic governments and judicial systems operate. In particular

there is a complete lack of natural justice, procedural fairness,

freedom of political discourse and other essential elements of rule

of law in the manner in which they exercise their power[23].This is well illustrated by the following examples.

The suspension of the Israellycool Facebook page by the First

Respondent as set out in the 20 November 2022 affidavit of David

Lange.The Respondents' admissions that in the first half of 2021 they

both suspended former US President Donald Trump from their

platforms[24].The First Respondents' admission that in February 2021 it

blocked news domains and pages from its Facebook platform in

Australia. This occurred when the Australian Parliament was

considering potential legislation making the First Respondent

pay publishers for content. There is also evidence that it also

took down pages of Australian hospitals, emergency services and

charities as part of a deliberately over-broad definition of

news.[25]The banning of the advertising of the entire cryptocurrency

industry, the subject matter of these proceedings, of which the

core legal documents and public announcements of the ban have

been admitted as authentic by the First Respondent.The use of automated tools to completely cut off the online life

of a parent trying to get medical help for his child and the

failure to rectify the clear injustice or provide proper

procedural fairness as illustrated by the story of Mark as told

by The New York Times.[26]

In circumstances where a prima facie case and public interest has

been established, refusal by this Court to exercise its jurisdiction

over companies which have such power, wealth and influence and have

wielded it in the manner outlined above against the sovereign nation

of Australia itself, the President of the United States and

arbitrarily and capriciously against both individuals and whole

industries would lead any reasonable member of the public to

conclude that these companies were above the law.This would bring the system of justice into disrepute and undermine

rule of law in Australia.

Mitigation and management of any harms using other Court powers

If the Court were to find that the concerns raised by the

Respondents have any real validity, it must first examine whether

such concerns can be managed or mitigated using other tools

available to the Court before exercising the most exceptional and

highly unusual power to stay these proceedings.[27]"The limited scope of the power to grant a permanent stay

necessarily directs an enquiry whether there are other means by

which the defect attending proceedings can be eliminated or

remedied."[28]The Court has extensive powers and many tools, including under Part

IVA of the FCAA, to manage proceedings, practitioners, costs and

approve settlements.Given the strong public interest considerations in these proceedings

outlined above, the very strong arguments against staying

proceedings and the real question as to whether the Court can now

refuse to exercise jurisdiction having previously actively decided

to exercise it on prima facie case and public interest grounds,

the use of other tools available to the Court must be preferred to

the extreme step of staying important public interest proceedings.If, despite the Applicant's arguments regarding lack of conflict of

interest above, the Court still has concerns about possible

conflicts of interest arising from the Applicant's discretion to

issue SUFB Tokens, then future issuances or sales of SUFB Tokens

could be made subject to Court approval. The applicant is willing to

make undertakings to this effect if the Court considers this

necessary.If, despite the benefits of self representation outlined above and

the Applicant's extensive legal skills and experience outlined

below, the Court still has concerns about the self-represented

Applicant's ability or resources to handle the complexities of a

large competition law class action or his obligations to group

members, an option exists for the Court to enable the appointment of

a top-tier law firm as solicitor on the record for the Applicant and

senior counsel or to provide legal support and guidance for the

self-represented applicant.In Okanagan, an important public interest case in Canada[29],

"the Supreme Court of Canada went one step further by holding that,

in very exceptional circumstances, the costs orders that may be made

in favour of those bringing public interest litigation include

ordering, early in the litigation, the defendant to provide advance

financing to the plaintiff to enable them to proceed with the

litigation."[30] [emphasis in original]The Canadian Supreme Court found that three requirements must be

satisfied for such an order to be made:the litigation would be unable to proceed if the order were not

made;the claim advanced by the plaintiff is prima facie meritorious;

andthe issues raised go beyond the individual interests of the

plaintiff, are of public importance, and have not been resolved

in previous cases.[31]

These proceedings clearly meet all three requirements as outlined in

these submissions and in prior submissions and evidence filed by the

Applicant[32].As noted, in Public Interest Cost Orders, an order requiring the

Respondents to provide advance financing or even fully fund the cost

of providing the Applicant with suitable big firm and senior

representation, or legal support is not foreign to the Australian

legal landscape.[33] Moreover, the Respondents' financial resources

are so great that such funding would place no financial burden on

them whatsoever.Moreover, while this would be an exceptional step, if the Court

considers exceptional steps are necessary to deal with the

Respondents' concerns, it is open to the Court to make such orders

and, on the basis of the above authority, this Court is obligated to

adopt these in preference to staying proceedings.

Legal Basis for Declassing Proceedings

In Perera, the Full Federal Court found that the power of the

Court under s 33N of the FCAA to order that proceedings no longer

continue as representative proceedings is quite limited in scope and

"requires consideration of the comparator of whether it is in the

interests of justice that proceedings be determined in numerous

individual non-representative proceedings."[34]This comparison requires each of the criteria at s 33N(1)(a) - (d)

to be assessed for both the current proceedings and numerous

individual non-representative proceedings.[35]"Section 33N(1) does not involve a comparison between the

representative proceedings and another identical or hypothetical set

of representative proceedings."[36]"The inquiry is not whether the common issues might be more

efficiently resolved by way of some other representative

proceedings."[37]In assessing each of the s 33N(1) criteria it is readily apparent

that the interests of justice are clearly in favour of the

proceedings remaining as representative proceedings.s 33N(1)(a): In these proceedings there are tens if not hundreds of

millions of group members. The costs of millions of individual

non-representative proceedings would obviously dwarf that of these

representative proceedings.s 33N(1)(b): These proceedings include damages claims on numerous

different bases and in relation to numerous different sub-classes

for millions of people. No non-representative proceedings could

obtain damages for persons other than the applicant in that

proceeding.s 33N(1)(c): While these proceedings involve millions of group

members, it is not until the damages stage that the particular

circumstances of group members will need to be considered. The

Applicant's claims in relation to Part IV breaches rely entirely

upon the conduct of the Respondents and not the particular conduct

of the Applicant or any group members. Thus liability can be

established in a very efficient and effective way by representative

proceedings whereas individual proceedings would involve massive

duplication of resources.s 33N(1)(d): The Respondents allegations of conflict of interest

arising from the litigation funding arrangements do not fall within

the terms of s 33N(1)(d). The litigation funding arrangements are

not relevant to the appropriateness of representative proceedings

themselves compared to non representative proceedings.Moreover, there are many other reasons why these representative

proceedings are more appropriate method to pursue the group members

claims than numerous non-representative proceedings. These include:because many group members's claims are too small to be

economically pursued individually, especially against the

economic might of the Respondents;because many group members rely upon the services of the

Respondents for their personal and business communications they

will naturally be reluctant to bring proceedings against the

Respondents because of the risk of their accounts being

suspended or being de-platformed;because Part IV competition law breaches in general and

unlawful cartels in particular are broad economic wrongs they

inherently have a large number of victims that may not even

realise they have been harmed by the unlawful conduct.

Indeed these proceedings amply fulfil the three internationally

recognised objectives of class action devices:

"First, by aggregating similar individual actions, class actions serve

judicial economy by avoiding unnecessary duplication in fact-finding

and legal analysis. Second, by distributing fixed litigation costs

amongst a large number of class members, class actions improve access

to justice by making economical the prosecution of claims that any one

class member would find too costly to prosecute on his or her own.

Third, class actions serve efficiency and justice by ensuring that

actual and potential wrongdoers modify their behaviour to take full

account of the harm they are causing, or might cause, to the

public."[38]

First Respondent's Contingency Fee Argument

The First Respondent asserts at [51 - 64] that the Applicant is

obtaining prohibited contingency fees by receipt of SUFB Tokens for

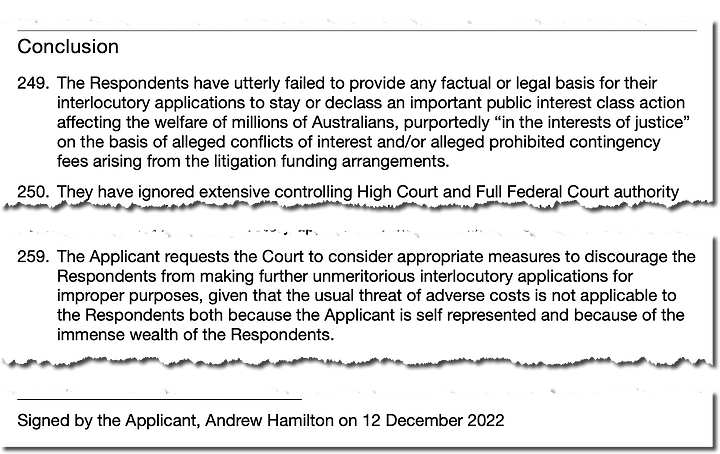

non-financial contributions to the prosecution of proceedings.An examination of the actual terms of prohibition on contingency

fees in s 183 of the Legal Profession Uniform Law (NSW), which

the First Respondent conspicuously fails to cite, reveals that it

clearly has no applicability to the Applicant's receipt of SUFB

Token for non-financial contributions.

"(1) A law practice must not enter into a costs agreement under which

the amount payable to the law practice, or any part of that amount, is

calculated by reference to the amount of any award or settlement or

the value of any property that may be recovered in any proceedings to

which the agreement relates."

In these proceedings the Applicant is not a law practice and there

is no costs agreement. The First Respondent has accepted that the

Applicant is not a law practice[39] and has not alleged that there

is a costs agreement.The First Respondent then cites and (mis)quotes[40] the 62 year old

case of Clyne v NSW Bar Association (1960) 104 CLR ("Clyne")

which, again, is clearly inapplicable on its own terms.In considering the applicability of maintenance and champerty (which

were then still illegal) to solicitors, the High Court said that a

solicitor "must not bargain with his client for an interest in the

subject matter of litigation, or (what is in substance the same

thing) for remuneration proportionate to the amount that may be

recovered by his client in a proceeding..."[41]In these proceedings there is no solicitor, no client and no bargain

between them. The First Respondent has accepted the first two facts

and implicitly the third.[42]Clyne was decided 33 years before the Maintenance, Champerty and

Barratry Abolition Act 1993 (NSW) and 46 years before Fostif

decided that the policy of the law had changed: "[t]he law now

looks favourably on funding arrangements that offer access to

justice so long as any tendency to abuse of process is

controlled."[43]In light of the above ratio decidendi in Fostif it is

questionable whether Clyne is still good law, at least in Federal

Courts, on the contingency fee issue. The statements regarding

contingency fees in Clyne are obiter dicta, as the Court there

was not called upon to determine whether there were unlawful

contingency fees.The First Respondent cites Bolitho v Banksia Securities Ltd (No 4)

[2014] VSC (Bolitho No 4) as authority for Clyne still

being good law on the contingency fee issue, but that case

inexplicably fails to consider the High Court authority of Fostif.

Fostif is binding on this Court while Bolitho No 4, being a

first instance Victorian case considering Victorian rather than

uniform national legislation, is not[44].In any case, the issue in Clyne that led to the High Court's

comments regarding contingency fees arose from a consideration of

the application of the then law of maintenance and champerty to

solicitors acting for a client. The effect of these comments is that

maintenance of proceedings is permitted to solicitors (that is their

legitimate business), but champerty is not.The abolition of the crimes and torts of maintenance and champerty

made both permissible to all, subject to remaining public policy

considerations. Fostif then reformulated these public policy

considerations in relation to litigation funding.It can thus be seen that residual public policy concerns about

maintenance in general and champerty in particular are the source

for all the First Respondent's cited legal authority in relation to

contingency fees.[45]These cases and resulting concerns about contingency fees are

completely inapplicable because the litigation funding arrangements

in the current proceedings do not involve maintenance at all, and

thus cannot involve champerty.Maintenance is variously described as:

the "assistance or encouragement of a party to an action in

which the maintainer had no interest"[46] (emphasis added)"the act of assisting the plaintiff in any legal proceedings in

which the person giving the assistance has no valuable

interest, or in which he acts from any improper motive.[47]

(emphasis added)

Thus it is completely impossible for the applicant in any

proceedings to be engaged in maintenance.In these proceedings not only does the Applicant have an interest in

the subject matter of proceedings independent of any litigation

funding arrangement, but so too does JPB Liberty and all Token

Holders, who hold Listed Cryptocurrencies and thus are group members

in the proceedings.In addition, because these are proceedings under Part IV of the CCA,

seeking an injunction under s 80 of the CCA, they are proceedings

which can be brought by anyone and where everyone has an interest -

that interest being the public interest.[48]There can be no champerty without maintenance as champerty is a

sub-species of maintenance[49].Thus, when analysed from first principles using binding High Court

authority, it is a complete absurdity to accuse the Applicant (or

any applicant) of obtaining prohibited contingency fees.

Professional Experience

The Respondents have unwisely[50] chosen to take issue with the

Applicant's professional experience, making incorrect and

misleading claims. This is despite it being clear from the evidence

and other documents filed in these proceedings that the Applicant

is a very experienced and senior solicitor with substantial

competition law, advocacy and class action experience[51].Both Respondents incorrectly and misleadingly allege that the

Applicant is "inexperienced with conducting class action

litigation" and that "there is no evidence to suggest that Mr

Hamilton has any substantial experience in conducting class actions

in Australia."[52]These submissions are misleading because the majority of legal

representatives conducting class action litigation in Australia

have no prior experience in doing so.

"Since 2005, between 51% and 70% of legal representatives acting for

class representatives had not previously acted on a class action. The

highest number, but lowest proportion, of inexperienced plaintiff

lawyers was shown to be from 2014 to 2017, when 51% (22) of legal

representatives in class action proceedings had no prior experience in

running class actions."[53]

These statements are incorrect because the Applicant does indeed

have experience in conducting class action litigation, which is

substantial by the standards set out above, and the evidence of

this has been on the Court record in these proceedings for over two

years.In particular, the case of Shurat HaDin, Israel Law Centre v Lynch

No. 2 [2014] FCA 413 (Shurat HaDin No 2), a representative

proceedings in which the Applicant acted as solicitor on the record

and advocate and obtained the second cost-capping order granted in

Federal representative proceedings[54] is cited in three documents

previously filed in these proceedings.[55]There are four reported judgements in those representative

proceedings in which the Applicant acted as solicitor on the record

and advocate, all of which are easily discoverable by a simple

search for "APS Hamilton" on www.austlii.edu.au.[56]This case has had substantial value as precedent[57] and Shurat

HaDin No 2 is cited a number of times in an important recent law

review article on the topic of public interest costs orders in

federal class actions[58], which is clearly relevant to these

proceedings, especially the Applicant's No Adverse Cost Order

application.Moreover, in baselessly impugning the Applicant's ability to manage

his fiduciary obligations to group members and the complexity and

technicality of cartel conduct representative proceedings, the

Respondents ignore the Applicant's legal seniority, experience,

skills and achievements as set out in his 2009 CV.In particular, the Applicant's role and achievements in the

landmark judgements in LK v Director-General, Department of

Community Services [2009] HCA 9 (11 March 2009) (LK)[59]

and Australian Communications Network Pty Ltd v Australian

Competition and Consumer Commission [2005] FCAFC 221 (25

October 2005) (ACN)[60] (ACCC application for special leave

to the High Court refused) represent career pinnacles which few

solicitors ever achieve. The renown legal practitioners with whom

the Applicant worked and successfully opposed both directly in

Court, and via legal arguments in these cases are a matter of

public record.Thus not only does the Applicant have substantial experience in all

areas of the law which are relevant to these proceedings, the

Applicant has made substantial contributions to the development of

the law over his legal career.Something also must be said about two additional matters:

the lack of respect for the Applicant's legal seniority to each

of the legal practitioners representing the Respondents in

these proceedings - the Court can take judicial notice of the

admission dates of all practitioners before it; andthe lack of competition law experience of most of the legal

representatives of the Respondents. The Court can take judicial

notice of the biographies of solicitors on the record and

counsel on their respective websites[61]. Only counsel for the

Second Respondent lists competition law experience in his

biography.

This is in sharp contrast to the extensive competition law

experience of the Applicant as set out in the 2009 CV, particularly

in the period 1994 to 2008. Telecommunications regulatory law

involves a significant competition law component, especially when

working for a former monopolist.It is ironic that in proceedings which substantially revolve around

the alleged unlawful cartel and anti-competitive concerted conduct

of the Respondents, the Respondents and their legal representatives

are engaging in cartel-like concerted conduct by advocating for

self-represented applicants to be excluded from bringing

representative proceedings.The Respondents' legal representatives are competitors in relation

to the provision of legal services to clients and advocacy services

in Court and the Respondents are competitors in relation to the

acquisition of these services. Their joint advocacy of excluding

self-represented applicants may be considered an arrangement or

understanding with the purpose or effect of providing for the the

controlling or maintaining of the price for legal and advocacy

services by excluding competition from self-represented

applicants[62]. It may also be considered concerted conduct with

the purpose or effect of substantially lessening competition in the

market for provision of class action legal and advocacy

services[63].Self-representation competes with the legal services offered by

solicitors and barristers and concerted conduct to exclude a class

of actual or potential competitors is problematic from both a

competition law and access to justice perspective.Perhaps if the Respondents' legal representatives had more

experience in competition law, the core subject matter of these

proceedings, rather than just litigation generally, they would see

how inappropriate it is to attempt to exclude self-represented

applicants from bringing representative proceedings.

Professional Conduct

The First Respondent has also unwisely chosen to raise the case

management history of these proceedings in an attempt to impugn the

Applicant's professional conduct and suitability to be a

representative applicant.A simple review of the correspondence preceding the 25 October 2022

case management hearing and the concessions by counsel for the

First Respondent in oral argument, reveals that hearing was

necessitated in part by the Respondents' failure to accept the

Applicant's repeated offer from 22 September 2022 onwards to create

and provide a document containing information regarding his related

parties, but only to the Respondents' external legal

representatives[64]. This offer was only finally accepted in oral

submissions at the 25 October 2022 case management hearing.[65]The hearing was further necessitated by the terms of the document

production orders drafted by the Respondents not being apposite to

the nature of the location of the relevant material (the Hive

blockchain) and genuine concerns to protect the identity and

private information of group members (including Token Holders), in

relation to which the Applicant was successful in obtaining

suitable protections.This is an example of the Applicant being perfectly capable of

protecting the interests of the group members and managing his

obligations to the Court.These proceedings have been on foot since August 2020 with very

extensive pleadings, evidence and submissions filed by the

Applicant. The Applicant has met every Court ordered timeline for

filing of material and has successfully navigated at least seven

case management and interlocutory hearings before two Judges, prior

to being granted leave to serve. Courts are naturally, initially

skeptical of a self-represented applicant bringing a class action

against the largest companies in the world for billions of dollars

in damages. The Applicant overcame that initial skepticism and has

successfully established a prima facie case and public interest

in these proceedings.In contrast, both Respondents failed to file their submissions on

this interlocutory application by the deadline set out in order 7

of the 27 October 2022 Orders, despite having months to prepare

them and two weeks to finalise them after the serving of the

Applicant's evidence.The First Respondent failed to file its interlocutory application

by the deadline set out in order 2 of the 21 September 2022 Orders,

despite it only being 4 sentences long and already in draft form at

the first case management hearing on 21 September 2022[66]. There

was no real basis for this failure arising from the disputes

regarding document production. This is evident from the First

Respondent's filed interlocutory application being substantially

the same as foreshadowed at the first case management hearing and

by the fact that the Second Respondent filed on time and later

sought a small amendment to match the First Respondent's

application.The First Respondent has conspicuously mis-named the Applicant as

"Paul Stuart Alexander Hamilton" in the 8 November 2022 affidavit

of Mark Anthony Wilks, thus also misnaming these proceedings. This

was brought to the attention of the First Respondent on 24 November

2022 and there has been no response from the First Respondent.These are relatively minor issues, but are nonetheless

unprofessional and undermine the implicit assumption underlying the

Respondent's attacks on self-represented applicants, that only a

big firm of solicitors can effectively conduct representative

proceedings.A far more serious issue is the First Respondent's conduct in

relation to David Hans Lange and Israellycool Israel Advocacy, as

set out in the 20 November 2022 affidavit of David Hans Lange and

the 21 November affidavit of Andrew Paul Stuart Hamilton at [10 -

13].The First Respondent's legal representatives have either allowed or

failed to prevent their client from suspending, arbitrarily and

without legitimate cause, the Facebook account of the only Token

Holder (a group member in these proceedings) whose Facebook page

was readily identifiable from the documents produced or listed by

the Applicant in response to document production orders. This is

despite a number of specific warnings about such conduct by the

Applicant prior to the relevant documents being produced.The First Respondent failed to respond to the Applicant's

correspondence of 17 November 2022[67] raising its concerns about

such conduct for almost 4 weeks. A letter containing a bare denial

was received by the Applicant less than 24 hours before these

submissions were due to be filed and served.It is clear that the administration of justice will be undermined

if respondents in representative proceedings are permitted to

suspend or withdraw services to those persons who join or fund

representative proceedings against them.No litigation funder would fund and no group member would be part

of proceedings against banks, telecommunications and utility

companies or big tech companies if there was even the perception or

possibility that doing so could lead to the withdrawal of these

services which are essential to modern life and business.This would substantially undermine Part IVA of the FCAA, bring the

administration of justice into disrepute and could potentially be

considered a perversion of the course of justice, especially when

the representative proceedings involve public interest in enforcing

Part IV of the CCA and may lead to criminal cartel prosecutions.

Cases cited by Respondents

[Wilkinson v Wilson Security Pty Ltd]{.underline}

As will already by evident from the examination of the Full Court

authority regarding the correct interpretation of s33N of the FCAA

in Perera above, the observations regarding s33N by Colvin J in

Wilkinson v Wilson Security Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 756

(Wilkinson) are, with respect, plainly wrong.Wilkinson failed to either recognise or apply the binding

authority of Perera.In addition Wilkinson has no precedential value or applicability

to the present proceedings because:the representative applicant did not contest the s33N

application;it was decided on the papers without the benefit of a hearing;

respondent counsel clearly failed in their obligation to bring

the binding authority of Perera, and other relevant authority

regarding fundamental rights to be heard by the Courts, to the

attention of the Court[68];the self-represented applicant had no legal experience and was

a security guard by profession - none of the concerns Colvin J

raised about that applicant[']{dir="rtl"}s capability to

prosecute proceedings or meet their fiduciary obligations are

applicable here;Colvin J, with respect, made an error of law in stating that

"Part IVA is silent on the question whether a representative

applicant can conduct representative proceedings without being

legally represented." In fact Part IVA makes no mention of

lawyers at all and the right of an an applicant to bring

representative proceedings is structurally an extension of

existing fundamental rights to be heard before the Courts.Colvin J cites a recommendation from Australia Law Reform

Commission (ALRC) Report No 46[69] published in 1988, that

representative applicants be legally represented[70] without

noting:the date of ALRC 46, 34 years ago;

the fact that Parliament declined to implement this

recommendation, while drafting Part IVA of the FCAA on the

basis of other recommendations of ALRC 46; andthat the subsequent report on representative proceedings in

2018, ALRC 134, did not made a similar recommendation;

the Fair Work jurisdiction is a very different one from Part IV

of the CCA. In particular it lacks the public interest

dimension referred to in Hamilton at [40].

The First Respondent attempts to justify both Respondents' heavily

reliance upon Wilkinson by incorrectly claiming that this Court is

bound to apply Colvin J's reasoning unless it is plainly

wrong.[71]But Farah does not stand for this proposition at all. Instead it

states at [135]:

"Intermediate appellate courts and trial judges in Australia should

not depart from decisions in intermediate appellate courts in another

jurisdiction on the interpretation of Commonwealth legislation or

uniform national legislation unless they are convinced that the

interpretation is plainly wrong." [emphasis added]

- Farah at [135] cites Australian Securities Commission v

Marlborough Gold Mines Ltd [1993] HCA 15; (1993) 112 ALR 627

which states at [4]:

"Although the considerations applying are somewhat different from

those applying in the case of Commonwealth legislation, uniformity of

decision in the interpretation of uniform national legislation such as

the Law is a sufficiently important consideration to require that an

intermediate appellate court - and all the more so a single judge -

should not depart from an interpretation placed on such legislation

by another Australian intermediate appellate court unless convinced

that that interpretation is plainly wrong". [emphasis added]

Wilkinson is not a decision of an "intermediate appellate court".

It is a trial judge decision made without a contradictor on the

papers and the "reasoning" cited by the Respondents is obiter

dictum, not the ratio decidendi of the case.I note that in addition to mis-stating the legal effect of Farah,

Respondent counsel in these proceedings have also failed to bring

the binding authority of Perera to the attention of the Court in

relation to the interpretation of s33N despite citing it elsewhere

in submissions.In such circumstances where respondent counsel fail in their duty to

the Court to disclose binding authority, it is perhaps not

surprising that a self represented applicant with no legal

experience, may be unable to effectively prosecute their case.

However the remedy for this is to enforce opposing counsel's

obligations, not to attempt to extinguish fundamental rights to be

heard by the Courts.

[Magic Menu Systems Pty Ltd v AFA Facilitation Pty Ltd]{.underline}

The First Respondent cites Magic Menu at [23] and [52] as

support for the following propositions:'that a stay may be justified "... where there may be real

potential for an abuse of the Courts' processes"';that the ability of the Courts to treat agreements for

maintenance as contrary to public policy, and therefore illegal,

remains unaffected by the statutory provisions (abolishing the

torts and crimes of maintenance and champerty).

On both propositions, Magic Menu has been superseded by the

decision of the High Court in Fostif, which the Respondents

conspicuously fail to bring the to the Court's attention.[72]Moreover the First Respondent's partial quote from Magic Menu at

[23] of its submissions is misleading, both as to what the Court

actual said and the fact that it was obiter dicta, not a holding

of the Court.The full text of the relevant paragraph is set out below:

"The New South Wales Law Reform Commission concluded, in its

Discussion Paper, with the observation that further consideration as

to the remedies which might be provided to the other party with

respect to interference in litigation, was necessary. These will

concern costs but may extend to other aspects of compliance with

procedures. Where more is involved, and where there may be the real

potential for an abuse of the Courts' processes it seems to us that a

stay might, in some cases, be justified. Whilst it had been said in

Martell v Consett Iron(388-9) (referred to in this respect in Hodges v

New South Wales [988] HCA 9; (988) 62 ALJR 90, 93) that it would not

be right to stay a maintained action, that was with respect to an

action brought on the tort and which had not been determined. It could

not then have been concluded that there was unlawful conduct and the

stay was, for that reason, premature. But that is different from the

position where an abuse of process has occurred, or is likely to. The

question whether a stay ought then be imposed was left open by Atkin

LJ in Wild v Simpson [99] 2 KB 544, 564. It is noteworthy however

that here a stay of the proceedings has never been sought. That

approach is consistent with there having been no allegation of an

abuse of process pleaded. We shall refer to this again later in these

reasons."[73] (emphasis added)

It is simply not good law to state that "a stay may be justified

where there may be real potential for an abuse of the Courts'

processes". The correct legal test and considerations are set out

under the heading "Legal Basis for Staying Proceedings" above.The second proposition for which the First Respondent relies upon

Magic Menu is again substantially narrowed and constrained, at

least in the context of litigation funding, by the High Court's

decision in Fostif[74].

[Bolitho v Banksia Securities Limited (No 4)]{.underline}

The inapplicability of Bolitho No 4, to these proceedings has

already been examined briefly above under the heading "First

Respondent[']{dir="rtl"}s Contingency Fee Argument."Bolitho No 4 concerns a solicitor and senior counsel, acting for a

representative applicant (Mr Bolitho) where the solicitor and

counsel (and their related parties) held a 90% interest in the

litigation funder funding the proceedings, which was charging a 30%

success fee.The Victorian Supreme Court's concerns about the above arrangement

arose primarily from concerns that it skirted the prohibition on

solicitors charging contingency fees.[75] It was not suggested

that the legislative prohibition on contingency fees was directly

applicable on its terms.Instead the Court relied upon the obiter in Clyne[76]

analysing the application of the then prohibitions on maintenance

and champerty, which concluded that a solicitor charging contingency

fees was a form of champerty and was thus prohibited.However as noted above, these concerns can never arise in relation

to the applicant in any proceedings because the applicant, by

definition, can never engage in maintenance of his own case and thus

cannot engage in champerty of his own case.While relying heavily upon Clyne, Bolitho No 4 failed to

consider either the abolition of the torts and crimes of maintenance

and champerty or the far more recent and binding decision of

Fostif which stated that the policy of the law had changed.It thus, with respect, cannot be considered good law on the issue of

solicitors charging contingency fees, even at the time it was made.Since the decision in Bolitho No 4, the Victorian Parliament has

passed legislative changes permitting solicitors to obtain

contingency fees in class actions[77] and ALRC 138 recommends that

contingency fees be permitted nationally[78] This substantially

changes the fundamental basis on which this case was decided.[79]

The views of a fair-minded, reasonable informed member of the public

(the Observer as defined in that case) about these matters have

changed substantially since 2014.Thus is it certainly not good law today on the issue of solicitors

charging contingency fees.In any case, the case is directed completely at the roles of

solicitor on the record and senior counsel, and the Court's

supervision of them, not the role of applicant. It is thus

completely inapplicable to these proceedings where there is neither

a solicitor on the record nor senior counsel appearing.Ordering a practitioner not to act is also a very different (and far

less serious) remedy than permanently staying proceedings that have

been regularly brought.This is further reinforced by the fact that the Court in Bolitho No

4 refused Mr Godfrey's application to restrain Mr Bolitho from

continuing to retain the solicitor and senior counsel, instead

ordering the solicitor and senior counsel to cease acting for Mr

Bolitho. The Court noted that its inherent jurisdiction is not about

restraining litigants from retaining lawyers of their choice.[80]The Court's statement that its inherent jurisdiction does not allow

it to interfere with a litigant's choice as to how he is represented

in Court, applies not just to choice of lawyers but also the choice

to act for oneself.As a first instance judgement from another Australian jurisdiction

in relation to Victorian state law (the powers of the Victorian

Supreme Court) rather than Federal or national uniform law it is

doubly not binding on this Court, and should not be considered

persuasive for the reasons set out above.Finally, one of the factors considered by the Court in Bolitho No 4

was that there was little risk of stultification of

proceedings.[81] In contrast, in these proceedings the risk of

stultification is great. Further, the risk of stultification of an

important public interest case affecting millions of Australians

cannot be compared to a small number of bond holders who had other

representation options to pursue their claims.

[Bolitho v Banksia Securities Limited (No 18) (Bolitho No

18)]{.underline}

The First Respondent cites Bolitho No 18[82] as support for the

proposition that the Applicant "is in substance acting as a

solicitor in the present proceedings, providing legal services to

himself as lead applicant"[83].Bolitho No 18 provides no support for this highly dubious

proposition whatsoever. It is not a case dealing with a self

represented applicant who is also a solicitor. It deals with the

control exercised by a solicitor (Mark Elliot) who was not the

solicitor on the record in the relevant proceedings.All the analysis of this issue in Bolitho No 18 is based on their

being a solicitor-client relationship, where the solicitor in that

relationship was not the real solicitor in control of the

proceedings.In these proceedings there is no solicitor-client relationship. The

suggestion that the Applicant is providing legal services to himself

is an entirely artificial attempt to create a solicitor - client

relationship inside the Applicant's head.The suggestion that a self represented applicant should be

considered to be providing legal services to himself is entirely

contrary to the Legal Profession Uniform Law (NSW) 2014

("LPUL").It would have the consequence that every self represented applicant

who was not a qualified entity was in breach of s 10 of the LPUL -

prohibition on unqualified entities engaging in legal

practice.[84]

[Clairs Keeley (a Firm) v Treaty (2004) 29 WAR 479 (Clairs

Keeley)]{.underline}

The first and obvious point to be made about Clairs Keeley is that

it is clearly no longer good law, having been overriden by

Fostif[85], which deals with the same subject matter and issues

and rules that the policy of the law with regard to litigation

funding has changed.The second point is that Clairs Keeley deals with maintenance and

champerty, whose inapplicability to these proceedings has been

analysed in detail above. In addition Western Australia has not yet

abolished the torts of maintenance and champerty[86] unlike NSW,

where the applicant is a solicitor and JPB Liberty is registered.The third point is that the main concern of the Court in Clairs

Keeley is the degree of control that the third party litigation

funder would exercise over the conduct of proceedings[87]. The

Court is concerned that the proceedings would be controlled

primarily by the funder rather than the applicant.This concern is obviously not applicable to these proceedings

because the Applicant controls JPB Liberty and thus the proceedings

are controlled exclusively by the Applicant. Companies are

controlled by their directors and shareholders, not the other way

around.In any case, the basis of Courts' concern regarding a funder

controlling a class action rather than the applicant is that the

funder is not in front of the Court or directly subject to its

control.This is not the case here. The person controlling these proceedings

is the Applicant who is most certainly in front of the Court.

Footnotes / Endnotes

Hamilton at [40] ↩

ibid. ↩

See Epic at [105] and [107] and Public Interest Cost

Orders at page 663 citing Australian Law Reform Commission, Costs

Shifting: Who Pays for Litigation (Report No 75, 1995) (ALRC

75) 147 recommendation 45. ↩See ConSub at [125 - 131]. ↩

See ConSub at [32 - 34]. ↩

See ConSub at [133 - 151]. ↩

Jago per Brennan J at [28]. See also Mason CJ at [20] ↩

Epic at [2]. Epic involves alleged breaches of ss 46, 47

and 45 (a) & (b) of the CCA while these proceedings involve alleged

breaches of ss 45AK, 45AJ, 45 (a) & (b) and 45 (c) of the CCA. ↩Epic at [97] ↩

Epic at [105] and [107]. ↩

Epic at [18]. ↩

Epic at [6]. ↩

Epic at [8 - 9]. ↩

Epic at [108]. ↩

Epic at [4]. ↩

The value of Australian consumer cryptocurrency holdings in early

2018 can be roughly estimated from the sample of the values of

funded group members cryptocurrency holdings of can be seen at MAW -

2 pages 196 -211, noting that over 25% of funded group members are

Australian and estimates of the number of Australian cryptocurrency

holders - See [9 - 10] and Annex B of Andrew Hamilton 23 October

2022 Affidavit. ↩See [36 -37] & [44] of 27 August 2020 affidavit of Andrew

Hamilton and [5] of 20 November 2022 affidavit of Andrew Hamilton. ↩See ACCC Digital Platforms Inquiry - Final Report ("ACCC

Report") at Annex L to 10 December 2020 affidavit of Andrew

Hamilton, particularly Recommendations 4, 5 on page 31and ongoing

investigations on page 38. The Court may also take judicial notice

under s 144 of the Evidence Act 1995 of the subsequent ACCC

inquiries and reports regarding Digital Platforms. ↩See [39 - 43] of 27 August 2020 affidavit of Andrew Hamilton

and [7] of 20 November 2022 affidavit of Andrew Hamilton. ↩See MAW - 2 page 453 ↩

See the Respondents' 2019 Annual Reports at Annexes C and D of 27

August 2020 affidavit of Andrew Hamilton, particularly their revenue

and cash reserves and the ACCC Report, particularly at page 4."A large part of this Inquiry has focussed on Google and Facebook.

This reflects their influence, sizeand significance. Google and Facebook are the two largest digital

platforms in Australia and theamount of time Australian consumers spend on Google and Facebook

dwarfs other rival applications and websites."The Court may also take judicial notice of the power and wealth of

the Respondents under s 144 of the Evidence Act 1995. ↩See ACCC Report page1 "The ubiquity of the Google and Facebook

platforms has placed them in a privileged position. They act as

gateways to reaching Australian consumers and they are, in many

cases, critical and unavoidable partners for many Australian

businesses, including news media businesses." ↩See examples and the ACCC Digital platform services inquiry

Interim Report No. 5 - Regulatory reform, September 2022 at section

4.2.3 on page 90 ,where the ACCC expresses concerns about digital

platforms unqualified discretion to suspend or terminate users

accounts and block content and section 4.3 on pages 98 - 102, where

the ACCC criticises the Respondents internal dispute resolution

processes for "lack of transparency", "lack of independence and

oversight over how digital platforms' terms, conditions and policies

are applied or enforced and how appeals are assessed." at section

4.3.1 on page 98. ↩See also pages 5-7 of Annex A to Andrew Hamilton 23 October 2022

affidavit. ↩id. at pages 9 -14. ↩

id. at pages 15 - 19. ↩

Fostif per Fostif Majority at [93] and [95]. ↩

Jago per Gaudron J at [16], See also Mason J at [15 - 18],

Brenan J at [17 - 20] and [23]; Deane J at [10 - 11] and

Toohey J at [24 - 29] all making the same point. ↩British Columbia (Minister of Forests) v Okanagan Indian Band

[2003] 3 SCR 371, 398 [38](LeBel J for McLachlin CJ, Gonthier, Binnie, Arbour, LeBel and

Deschamps JJ) (Okanagan). ↩Public Interest Cost Orders at 665, citing Okanagan at 400

[41]. ↩Okanagan at 399--400 [40]. ↩

See ConSub and the Applicant's submissions to the 11 September

2020 interlocutory hearing at [28 - 64] (regarding the Applicant's

application for a No Adverse Costs Order). ↩Public Interest Cost Orders at footnote 82, citing the

Australian Tax Office's Test Case Litigation Program. ↩Perera at [60]. ↩

id. at [60 - 61]. The Second Respondent cites Kikuyu v

Hazzard [2022] FCA 310 at [4] as authority for a different test

than established in Perera. However, with respect, this case is

not good law on the question because it failed to cite or consider

the binding authority of Perera. Lee J did not have the benefit of

a contradictor as the de-classing was unopposed and the judgement

was delivered ex tempore. ↩id. at [61]. ↩

ibid. ↩

Public Interest Cost Orders at page 659 citing Hollick v City of

Toronto [2001] 3 SCR 158, 170 [15] (McLachlin CJ for the

Court). ↩Meta submissions at [11]. ↩

The quote from Clyne at 203 set out on page 18 of Meta's

submissions is missing the words "since it is, in a sense, the

business of a solicitor" in the second line between "solicitor" and

"to maintain". ↩Clyne at 203. ↩

Meta Submissions at [11]. ↩

Fostif at [65] per Fostif Majority. ↩

Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (2007) 230 CLR 89

("Farah") at [135] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Callinan, Heydon

and Crennan JJ; Australian Securities Commission v Marlborough Gold

Mines Ltd [1993] HCA 15; (1993) 112 ALR 627 at [4]. ↩Magic Menu Systems Pty Ltd v AFA Facilitation Pty Ltd (Magic

Menu) (1997) 72 FCR 261; Clyne and Bolitho No 4; Bolitho v

Banksia Securities (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (in lie) No- [2021] VSC (Bolitho No 18)

Magic Menu at 268. ↩

Fostif at footnote 58 per Fostif Majority citing A Digest of

the Criminal Law (Crimes and Punishments), (1877) at 86. ↩Truth About Motorways Pty Limited v Macquarie Infrastructure

Investment Management Limited [2000] HCA 11 at [9, 13, 20] per

Gleeson CJ & McHugh J [26, 30] per Gaudron J [71, 73] per Gummow

J; Phelps v Western Mining Corporation Ltd (1978) 20 ALR 183 at

[189]; Epic at [23 - 24]; Hamilton at [40]. See also

discussion at ConSub at [158 - 176]. ↩Fostif at footnote 58 per Fostif Majority and Magic Menu at

The Applicant would have preferred to avoid the unseemly

comparison of the relevant professional experience of all the

experienced legal practitioners appearing before the Court in these

proceedings, but the Respondents unjustified attacks on the

Applicant's professional experience and conduct cannot go

unanswered. ↩See the Applicant's 2009 Curriculum Vitae at Annex F to the 27

August 2020 affidavit of Andrew Hamilton ("2009 CV") and class

action experience discussed below. ↩Meta submissions at [82 -84]; Google submissions at [67 (c)

and (d)] ↩See ALRC 134 at [3.42] citing Vince Morabito, [']{dir="rtl"}The

First Twenty-Five Years of Class Actions in Australia: An Empirical

Study of Australia[']{dir="rtl"}s Class Action Regimes, Fifth

Report[']{dir="rtl"} (July 2017). ↩See Petrovski, Bill; Li, Katrina; Morabito, Vince; Nichol, Matt

--- "Public Interest Costs Orders in Federal Class Actions: Time

for a New Approach" [2022] MelbULawRw 7; (2022) 45(2) Melbourne

University Law Review 651 (Public Interest Cost Orders) at

Part V. ↩See footnote 4 of the Applicant[']{dir="rtl"}s submissions filed

on 11 December 2020; List of authorities filed on 10 December 2020

and Complete List of Authorities filed on 1 March 2021. ↩Shurat HaDin, Israel Law Center v Lynch [2014] FCA 226;

Shurat HaDin No. 2; Shurat HaDin, Israel Law Center v Lynch (No

3) [2014] FCA 749; Shurat HaDin, Israel Law Center v Lynch (No

4) [2014] FCA 1216. ↩Shurat HaDin No. 2 has been cited in 20 cases and two law

journal articles. See

[https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/LawCite?cit=[2014]%20FCA%20413]{.underline} ↩Public Interest Cost Orders ↩

LK has been cited in 155 cases and four law journal articles.

See

[https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/LawCite?cit=[2009]%20HCA%209]{.underline} ↩ACN has been cited in 15 cases. See

[https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/LawCite?cit=[2005]%20FCAFC%20221]{.underline} ↩https://tenthfloor.org/barrister/matthew-darke-sc/;

https://www.banco.net.au/barristers/robert-yezerski;

https://www.corrs.com.au/people/mark-wilks;

https://www.herbertsmithfreehills.com/our-people/leon-chung ↩See CCA s45AD (2) (b). ↩

See CCA s 45(1)(c). Only a single member of a cartel or

participant in concerted conduct group needs to be a constitutional

corporation for these provisions to effectively apply to all

participants. ↩See MAW - 2 at page 78. ↩

See Transcript at MAW - 2 at page 163 lines 26-27 ↩

See Meta position paper at the first case management hearing. ↩

At page 1 of Exhibit APSH - 1 to 21 November 2022 Affidavit of

Andrew Hamilton. ↩LEGAL PROFESSION UNIFORM CONDUCT (BARRISTERS) RULES 2015 - REG

29 ("Barrister Reg 29") ↩Grouped Proceedings in the Federal Court [1988] ALRC 46

("ALRC 46") ↩Wilkinson at [13]. ↩

Meta Submissions at [71] citing Farah. ↩

In potential breach of Barrister Reg 29. ↩

Magic Menu per Lockhart, Cooper and Kiefel JJ at 268-269. ↩

Fostif at [63 -95] and particularly [63] & [93] per

Fostif Majority. ↩Bolitho No 4 at [50 - 51]. ↩

at 203. ↩

See s 33ZDA of Supreme Court Act 1986 (Vic). ↩

ALRC 138 Recommendation 138 at page 11. ↩

Bolitho No 4 at [50] ↩

Bolitho No 4 at [32] ↩

id. at [55]. ↩

Bolitho No 18 at [88] per Dixon J. ↩

Meta submissions at [57]. ↩

s 6 of the LPUL provides that "legal services means work done,

or business transacted, in the ordinary course of legal practice;" s

10 (1) of LPUL provides "An entity must not engage in legal practice

in this jurisdiction, unless it is a qualified entity." ↩As outlined in detail throughout the above submissions. ↩

The Law Reform Commission of Western Australia recommended their

abolition in "Maintenance and Champerty in Western Australia,

Project 110: Final Report", February 2020 at Recommendation 1. ↩See Clairs Keeley at [57 - 79] and [124], [126], [130]

and [132]. ↩