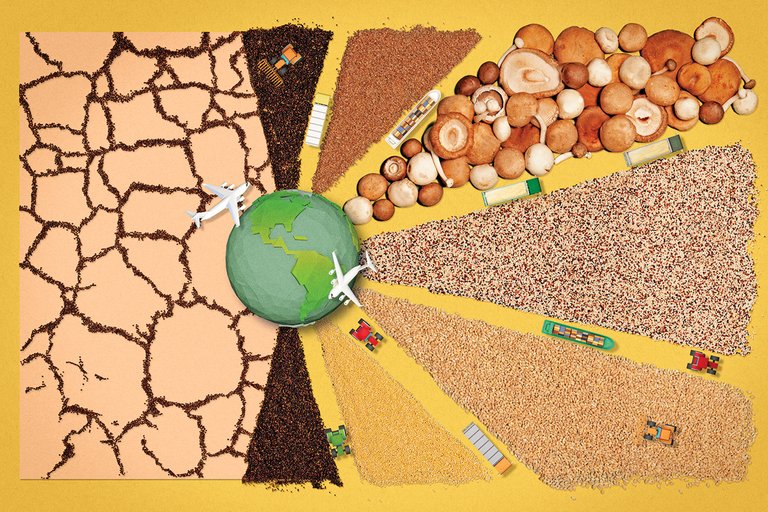

The war in Ukraine has brought about an alarming global increase in government controls over food exports. It is critical that policy makers halt this trend, which increases the likelihood of a global food crisis.

Undoubtedly, food crises are bad for everyone, but they are devastating for the poorest and neediest. This is due to two reasons: First, the poorest countries in the world are usually food importers. Second, food accounts for at least half of all household expenditures in low-income countries. For example, the food crisis in 2008 caused a significant increase in malnutrition cases, particularly among children. Many families had to mortgage their valuables in order to buy food. Some studies showed that school dropout rates reach 50% among the children of the poorest families. This kind of social and economic damage cannot easily be reversed.

In just a few weeks, the number of countries imposing food export restrictions increased by a whopping 25%, bringing the total number to 35. The most recent data showed an intervention of export restrictions, and 9 interventions included restrictions on wheat exports. And history shows that restrictions of this kind are counterproductive in the most tragic way. A decade ago, in particular, those restrictions exacerbated the global food crisis, causing the price of wheat to increase by a whopping 30%.

Currently, despite the speed with which export and import restrictions have been imposed, they are not as extensive as they were a decade or so ago. For example, export and import restrictions currently cover about 21% of world trade in wheat - far below the 75% at the height of the food crisis in 2008-2011. However, the conditions are ripe for a cycle of retaliation in which restrictions may increase rapidly.

Trade measures are already having a clear impact on food prices. Russia imposed restrictions on wheat exports to countries outside the Eurasian Economic Union. In addition to Russia, smaller exporters such as Serbia and North Macedonia have restricted exports. Food importers such as Egypt - which imports 80 percent of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine and is concerned about re-exports - have followed suit. These measures alone cover 16% of world trade volume and were the cause of a seven percentage point increase in world wheat prices. This percentage is equivalent to about one-sixth of the total increase in prices.

Commercial Interventions

The sharp increase in trade interventions in March may be a clue to future supply disruptions. Food export restrictions imposed in March were almost double the number imposed in the previous two months. Measures restricting exports reduce global supply, leading to higher prices. This causes new export restrictions to contain domestic price pressures, which leads to a "multiplier effect" on world prices. Should any of the five largest wheat exporters ban exports, the cumulative effect of these measures would be to increase world prices by at least 13%—and much more if the other exporters reacted.

So, it is time to defuse the danger. A global food crisis is by no means an inevitable destiny. Despite the extraordinary recent rise in food prices, global stocks of the three main commodities - rice, wheat and maize - remain large by historical standards. The G7 recently took the important step of pledging not to impose bans on food exports and to use "all tools and financing mechanisms" to enhance global food security. This group already includes many of the largest commodity exporters - including the United States, Canada and the European Union. Major food exporters such as Australia, Argentina and Brazil should join this commitment.

Finally, maintaining global food flows, especially at a time of heightened economic and geopolitical pressures, should be a minimum required of policymakers everywhere, the equivalent of a do no harm rule. The uninterrupted provision of food aid benefits the citizens of all countries. It would also give national policymakers a much better chance of overcoming all the other shocks from the war in Ukraine.