El hombre se paró frente a la tienda. Tenía que estar allí antes de que los demás llegaran aunque suponía también que los empleados lo corrieran. Llevaba sus cajas de cartón, una cobija roída y maloliente y la ropa en una bolsa. Miraba a todos lados, esperando a que cerraran la tienda para instalarse.

Dio un suspiro. Los vendedores lo miraban con reojo y las personas se tapaban la nariz al pasar a su lado. Algunos le daban algún billete de poco valor. Esta vez no le dijeron nada, y cuando cerraron pudo ir acomodando sus cosas poco a poco.

Lo hacía con una calma desesperada, pues sabía que en cualquier momento llegarían los demás y todo se convertiría, como sucedía con mucha frecuencia, en un campo de batalla.Tomó sus cosas y se sentó sobre los cartones. Ya la tarde iba cayendo y veía a la gente caminar, algunos desesperados por llegar a casa, otros caminando despacio, parejas tomadas de la mano, madres con sus niños pequeños vestidos con sus uniformes escolares arrastrados por ese caminar rápido mientras ellos iban rezongando debido al sueño y el cansancio.

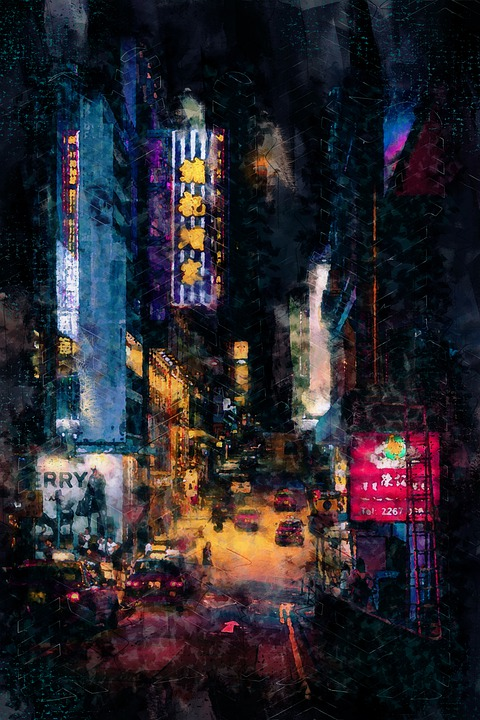

Miraba, siempre miraba. Hablaba muy poco. Del manojo de cosas que tenía sacó un lápiz y un cuaderno. Cuando podía, cuando no lo molestaban los demás, hacía dibujos y escribía. Dibujaba a esas personas que veía transitar en la noche. Borrachos, prostitutas, indigentes, como él, buscando en la basura, mirando el cielo o refugiándose de la lluvia. También dibujaba a los jóvenes universitarios que salían de las discotecas y los bares, y una que otra vez, dibujaba, desde el recuerdo remoto, destellos de su infancia.

De todos los retratos, tenía uno muy especial. Era el de aquella muchacha que se aparecía de vez en cuando, junto con otras personas, para llevarles algo de comer. Él, como era su costumbre, se mantenía alejado del grupo. Entonces esta joven se acercaba, con una sonrisa, un envase y una taza de chocolate caliente.

Todos los jueves llegaba el grupo de jóvenes con las viandas, y él esperaba en su lugar, sin moverse, sin abandonar sus pocas pertenencias. Entonces se acercaba ella. Una de esas noches le preguntó por su nombre. Él entonces comenzó a contar su historia, una más que a lo mejor ella habrá escuchado. Mientras hablaba ella escuchaba con interés, le hacía preguntas, y él volvía atrás, más atrás, a su infancia, a sus días de felicidad, a los años de formación y a los de perdición; le contó de sus novias y de su esposa, de las borracheras y el consumo de drogas, del fracaso en la universidad y como padre, del alcoholismo y de los días sin dormir, de los viajes psicodélicos y de los reales, sin saber distinguir entre la realidad y la alucinación.

Le contó, en pocas palabras, su vida. Entonces le dio el retrato que le había hecho, y la joven sonrío agradecida. A partir de ese día las conversaciones fueron constantes, él encontró un refugio en su propia voz. Había pasado mucho tiempo sin escucharse a sí mismo, y encontró un ángel en la presencia de aquella joven.

Fue entonces cuando ella le pidió más retratos, más dibujos, y él se los fue dando. Fue entonces cuando ella lo invitó a una galería, lugar en el que él no podía entrar, no porque no quisiera sino porque no lo dejarían entrar. Sin embargo, la joven se las ingenió para que él pudiera asistir.

A medida que iba viendo la galería, los cuadros, las hojas de cuaderno, se dio cuenta de que aquello era suyo. Todos los dibujos que le había dado a aquella chica estaban ahí. Veía a las personas maravillarse de aquellos retratos, de las vidas nocturnas que por mucho tiempo él logró plasmar desde la miseria en la que se encontraba.

English version

The man stood in front of the store. He had to be there before the others arrived even though he also assumed the employees would run him off. He was carrying his cardboard boxes, a gnawed and smelly blanket and clothes in a bag. He looked around, waiting for them to close the store so he could settle in.

He gave a sigh. Vendors looked at him sidelong and people held their noses as they passed him. Some gave him a few small bills. This time they didn't say anything to him, and when they closed he was able to slowly arrange his things.

He did so with a desperate calm, for he knew that at any moment the others would arrive and everything would become, as it so often did, a battlefield. He took his things and sat down on the cardboard. Already the afternoon was falling and he saw people walking, some desperate to get home, others walking slowly, couples holding hands, mothers with their small children dressed in their school uniforms dragged by that fast walking while they were grumbling due to sleep and tiredness.

He watched, always watched. He spoke very little. From the bundle of things he had pulled out a pencil and a notebook. When he could, when he was not disturbed by others, he drew pictures and wrote. He drew those people he saw passing by at night. Drunks, prostitutes, homeless people, like him, searching through the garbage, looking at the sky or taking shelter from the rain. He also drew the young university students coming out of the discos and bars, and once in a while, he would draw, from a distant memory, flashes of his childhood.

Of all the portraits, he had a very special one. It was the one of that girl who appeared from time to time, along with other people, to bring them something to eat. He, as was his custom, stayed away from the group. Then this young woman would approach, with a smile, a container and a cup of hot chocolate.

Every Thursday the group of young people arrived with the food, and he waited in his place, without moving, without leaving his few belongings. Then she would approach. One of those nights she asked him for his name. He then began to tell his story, one more that she might have heard. As he spoke she listened with interest, asked him questions, and he went back, further back, to his childhood, to his days of happiness, to the formative years and those of perdition; he told her of his girlfriends and his wife, of drunkenness and drug use, of failure in college and as a father, of alcoholism and sleepless days, of psychedelic trips and real ones, not knowing how to distinguish between reality and hallucination.

He told her, in a nutshell, about his life. Then he gave her the portrait he had made for her, and the young woman smiled gratefully. From that day on the conversations were constant, he found a refuge in his own voice. He had gone a long time without listening to himself, and he found an angel in the presence of that young woman.

It was then that she asked him for more portraits, more drawings, and he gave them to her. It was then that she invited him to a gallery, a place he could not enter, not because he did not want to, but because they would not let him in. However, the young woman managed to get him to attend.

As he saw the gallery, the paintings, the notebook pages, he realized that this was his. All the drawings he had given to that girl were there. He saw people marveling at those portraits, at the nocturnal lives that for a long time he had managed to capture from the misery in which he found himself.