Hi Everyone,

Welcome to the tenth and final post in my conference and journal paper post series. This series contains conference and journal papers from my time working in the Queensland Government. In my post, My Peer Reviewed Conference and Journal Papers, I explain the purpose of this series.

How Assumptions Influence the Results of a Cost Benefit Analysis was the only paper I wrote while working for Building Queensland. I presented this paper at the 2016 ARRB Conference. The paper was more closely linked to my previous job at Transport and Main Roads. Therefore, I funded the research and presentation for the conference myself.

This was arguably my most controversial paper. I explored the many assumptions that can be applied to a cost benefit analysis and how they can influence the results. Economists can tinker with assumptions to give them the results that the Government wants. This paper looks at assumptions around the base case, transport and traffic modelling, demand forecasts, road user behaviour, and several others. The paper uses data from actual projects and compares the results under different assumptions. For some projects, the variation in results is astonishing. It is possible to make any project look good with the ‘right’ assumptions.

The paper was well received by other attendees. They appreciated that I had revealed a much deeper problem in how the Government and consultants approach and use cost benefit analysis. I was not approached by anyone from Transport and Main Roads.

In 2017, I left Building Queensland. This meant I was out of the Government. I still did work for the Government as a private consultant, but I no longer had access to data and information that I could use to write compelling papers. In 2019, I left Australia to return to the UK. I have not worked with the Queensland Government since.

HOW ASSUMPTIONS INFLUENCE THE RESULTS OF A COST BENEFIT ANALYSIS

ABSTRACT

The national guidelines for transport systems management (NGTSM) provides guidance for how cost benefit analysis (CBA) should be conducted for transport and road projects. These guidelines are supplemented by material provided by the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE), Austroads and the state road authorities. This paper attempts to investigate if following the guidelines alone is always sufficient to achieve both transparency and consistency for CBAs.

In this paper, a number of real life case studies from Queensland have been included. These case studies include road interchange upgrades, bridge upgrades, flood immunity improvements, and public transport projects. The CBAs of the case studies follow the guidelines provided (consistent unit values and formulae) but the results of the CBAs fluctuate for reasons outside of the material provided in the guidelines. These reasons largely relate to the adoption of assumptions. The assumptions considered in this paper relate to the base case, the use of transport models, treatment of incomplete information and data, road user behaviour, and forecast demand.

The paper proposes evaluating projects as part of a program as an approach to mitigate or resolve inconsistencies between CBAs that might use different assumptions if evaluated as individual projects. The problems identified in the case studies are revisited and discussed in the context of a program approach. The paper discusses how the application of a program approach enhances the value of CBA outputs to decision-makers.

1. INTRODUCTION

The national guidelines for transport systems management (NGTSM) provides guidance for how cost benefit analysis (CBA) should be conducted for transport and road projects. These guidelines are supplemented by material provided by the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE), Austroads and the state road authorities. These guidance materials provide the economic concepts, formulae and unit values for analysts to apply to transport and road CBAs. One of the aims of the guidelines and supporting material is to ensure that CBAs for transport and road projects are transparent and consistent (NGTSM 2016). This paper attempts to investigate if following the guidelines alone is always sufficient to achieve both transparency and consistency for CBAs.

For transport and road project CBAs, costs and benefits are typically required to be forecast over an evaluation period of about 30 years. The length of the evaluation period adds a high degree of uncertainty. Assumptions are often required to deal with the uncertainty. To ascertain the effect assumptions could have on the results of CBAs, this paper investigates a number of transport and road project case studies from Queensland. The case studies include projects such as road interchange upgrades, bridge upgrades, flood immunity improvements, and public transport projects. The assumptions considered in this paper relate to the base case, the use of transport models, treatment of incomplete information and data, road user behaviour, and forecast demand.

The paper proposes that all highlighted problems can be either resolved or mitigated by adopting a program approach for delivering transport solutions. Projects are typically evaluated in isolation to each other. This approach is susceptible to producing inconsistent assumptions between projects. This inconsistency might hinder the effectiveness of CBA as an approach to compare projects that are competing for funds from the same funding source; this is evident in the case studies discussed in this paper. The adoption of a program approach has the advantage of enabling a more consistent approach to project assumptions for all projects within a program. Improved consistency of the treatment of project assumptions resolves or mitigates almost all the problems identified in the case studies. A program approach also has a number of other advantages that are briefly discussed in this paper.

2. BASE CASE ASSUMPTIONS

Defining the base case is one of the most important steps in conducting a CBA. The base case is the reference point that all project options are compared with (Department of Treasury and Finance 2013). It is also one of the steps that is typically not dealt with in sufficient detail (Tveter 2013). Assumptions applied to the base case can vary depending on the analysts and project teams involved. The base case can be defined as a ‘do nothing’ or a ‘do minimum’ option. A ‘do nothing’ option is sometimes taken literally, as ‘do nothing’ but instead, it should be assumed as a business as usual option (Civil Aviation Safety Authority 2007). A ‘do minimum’ option requires intervention to maintain the serviceability of the current assets but this intervention is less costly than the proposed options (Australian Transport Council 2006).

2.1. Maroochydore Road Interchange

The Maroochydore Road Interchange Upgrade is an example of a project where lack of base case definition and modelling greatly influenced the results of the CBA. The Maroochydore Road Interchange is located west of Maroochydore at the intersection of the Bruce Highway, Maroochydore Road, and Nambour Connection Road. In the options analysis, three project options and a base case were considered. The base case was a ‘do nothing’ option and one of the project options was a ‘do minimum’ option. Maroochydore Road Interchange is almost at capacity; given the forecast traffic growth, the interchange is expected to reach capacity before any project option can be constructed. In the base case, it has been assumed, the existing interchange will be gridlocked during peak hours for the whole 30-year evaluation period. The ‘do minimum’ option proposed low cost interventions to improve the flow of traffic. The ‘do minimum’ option had an initial capital outlay of approximately $11 million. The other two project options (project options 6 and 6A) had capital costs of approximately $200 million (Aurecon 2015).

In the 2015 CBA report, at a discount rate of 7%, the benefit cost ratios (BCR)s of the ‘do minimum’, 6, and 6A were reported as 15.7, 4.8, and 4.6 respectively and the net present values were reported as $113.2 million, $407.2 million and $396.5 million respectively. If the ‘do minimum’ option had been reported as the base case, the BCRs of project options 6 and 6A would have been 4 and 3.8 respectively and the NPVs would have been $294 million and $283.3 million respectively. The BCRs of the project options would have fallen by about 0.8 and the benefits would have fallen by over $110 million. This does not affect the economic viability of the project options. Maroochydore Road Interchange Upgrade is revisited later in this paper in the context of economic modelling and the treatment of incomplete information.

2.2. Arnot Bridge

The Arnot Bridge Upgrade project, which was located just north of Townsville along the Bruce Highway, was a proposal to replace the existing structurally unsound bridge. The bridge was expected to be subject to load restrictions within the next five years and was expected to be closed to all vehicles within the next 10 years (TMR 2015a). It was assumed in the base case that a sidetrack would be put in place. The sidetrack was expected to be flooded for four months of the year. During those four months, vehicles have been assumed to divert and travel an additional 330km. Another project, the Ingham to Cardwell deviation, is expected to become part of the Bruce Highway, hence heavy vehicles will no longer need to cross the Arnot Bridge. The timing of the Ingham to Cardwell deviation was unknown at the time of the Arnot Bridge CBA but an assumption that the deviation will be complete in 15 years was used in the CBA.

In the 2015 CBA report, at a discount rate of 7%, the BCR of the Arnot Bridge Upgrade was 98.26. Changes to the timing of the bridge closure and the opening of the deviation were included in the sensitivity analysis. If the deviation is completed before load restrictions or road closures are required, the BCR of the project falls to just 0.75 (TMR 2015a).

3. THE USE OF DIFFERENT MODELS (TRANSPORT AND ECONOMIC)

There is a range of different transport models available. These models can be broadly categorised as macroscopic, mesoscopic, and microscopic models. These types of models differ in terms of detail and breadth of analysis. Macroscopic models cover a large portion of the transport network and generally do not produce detailed outputs. Mesoscopic models isolate part of the transport network and offer more detailed analysis than the macroscopic models. Microscopic models isolate small discrete sections of the network such as individual intersections; these models produce results at the individual vehicle level (Transport, Roads and Maritime Services 2013). Typically, either mesoscopic or microscopic outputs are applied to the CBA. The results produced by different transport models within the same category can vary significantly depending on the capability of the model and the assumptions applied to the model.

3.1. Northern and Eastern Transitways

The Northern Transitway and the Eastern Transitway projects were analysed using two different transport models. The Northern Transitway was proposed to be located north of the Brisbane CBD along Gympie Road between Kedron and Chermside. The Northern Transitway project proposed to utilise existing infrastructure to provide the new bus lanes (TMR 2014a). The Eastern Transitway was proposed to be located along Old Cleveland Road between Coorparoo and Carindale. The Eastern Transitway project also proposed to use existing infrastructure as well as upgrade a number of intersections to facilitate the new bus lanes (TMR 2014b).

Transport modelling for the Northern Transitway was conducted using the VISSIM model. Transport modelling for the Eastern Transitway was conducted using the AIMSUN model. Both VISSIM and AIMSUN can be described as hybrid mesoscopic and microscopic transport models. For the two CBAs, both models produced outputs of passenger kilometres travelled (PKT), passenger hours travelled (PHT), vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT), and vehicle hours travelled (VHT). The transport modelling outputs for the two transitway projects were both analysed using the same Transport and Main Roads’ economic model. The proposed Northern Transitway is 3km. The analysis conducted using VISSIM covered an average distance travelled of approximately 18km per vehicle (TMR 2014a)1 . The proposed Eastern Transitway covered a 5km section but the upgraded section of road is approximately 2km. The analysis conducted using AIMSUN covered an average distance travelled of approximately 2km per vehicle (TMR 2014b). It was not transparent in the reports if the scope of the analysis was related to the selection of models or the assumptions applied by the project teams to the models.

In the 2014 CBA reports, at a discount rate of 7%, the Northern Transitway had a BCR of 3.6 and the Eastern Transitway had a BCR of 1.43. Considering the similarities in the project scopes and location, the use of different transport models did not appear warranted. It is impossible to determine how accountable the different transport models are for the differences in BCRs. Hence, it would be misleading to make direct comparisons between these two projects.

In the initial CBAs conducted in 2012, the BCRs for the Northern and Eastern Transitways were 1.8 and 1.6 respectively (Office of the Infrastructure Coordinator 2013). The assessment did not disclose the discount rate or the models used to evaluate the projects. The project scopes outlined in 2014 did not appear substantially different from the project scopes outlined in 2012. Therefore, the BCRs in the updated CBA reports should not be expected to change substantially for either project.

3.2. Coomera Interchange

The Coomera Interchange Upgrade was initially analysed using SIDRA and then later with AIMSUN. The Coomera interchange is located at the Pacific Motorway Exit 54 off-ramp. The interchange connects the off-ramp with Abrahams Road and Days Road. In an attempt to reduce queuing on the off-ramp, a new link road connecting to Abrahams Road was proposed (TMR 2008a).

The close proximity of other intersections to the Coomera interchange rendered the initial results produced in SIDRA inaccurate. For the 2018 PM peak period, the SIDRA analysis produced delays in excess of 30 minutes in the base case and in excess of 13 minutes in the project case. In the August 2008 CBA report, at a discount rate of 7%, the calculated BCR using this data was 2.1 (Main Roads 2008a). The AIMSUN analysis produced significantly lower delays in both the base case and the project case. For the 2018 PM peak period, AIMSUN produced delays of 5 ½ minutes in the base case and just under 5 ½ minutes in the project case. In the November 2008 CBA report, the BCR fell to just 0.1 (Main Roads 2008b).

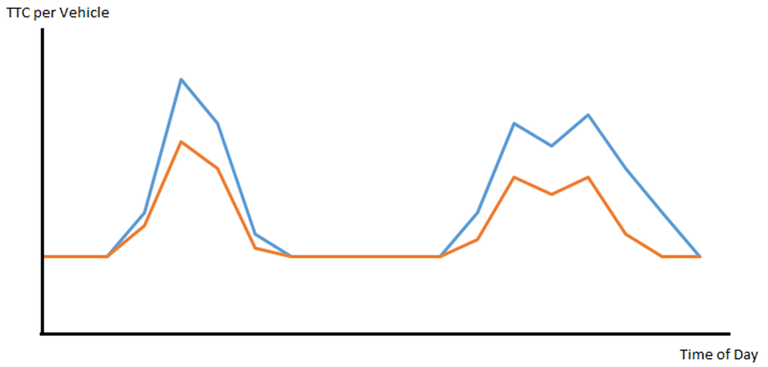

The low BCR prompted a rerun of the AIMSUN analysis for the project case. The updated analysis revealed delays in the project case had dropped to 5 minutes. A different team of analysts updated the CBA. This CBA included off-peak benefits. In the absence of off-peak traffic analysis, it was assumed that the peak period accounted for only 11% of daily costs (SKM 2009); this figure was extrapolated from the Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics (BTRE), Working Paper 71, (BTRE 2007). An expansion factor of 100/11 was applied to the peak period costs to determine the total daily costs. This assumption resulted in 89% of the project benefits being accounted for during the off-peak period. In the 2009 CBA report, at a discount rate of 7%, the BCR rose back to 2.1. Based on the data available, assuming such a high percentage of off-peak benefits is very optimistic. This optimism most likely greatly over-estimated the results of the CBA. Given the data provided, Figure 1 shows an alternative and more conservative representation of the base case and project case costs if it is assumed that delays do not exist in the base case.

Figure 1: Likely Cost Distribution per Vehicle

Figure 1 shows the reduction in peak hour costs derived from the data available. The off-peak costs are assumed close to unchanged when traffic is free flowing in the base case. Eventually the peak periods are likely to spread as congestion grows. Ideally, modelling should be conducted to support any hypothesis put forward.

3.3. Economic Models (Maroochydore Road Revisited)

The use of different economic models can also pose problems in the consistency of a CBA. For CBAs conducted in-house, TMR generally uses the same set of economic models for the same project types (TMR 2011a). The use of the same models improves the consistency of the analysis and continued usage reduces errors in the models.

TMR also hires consultants to conduct CBAs. The economic models produced by consultants are often customised to the project. Customised models are good at isolating benefits and costs not included in the generic models but they also create the problem of consistency with existing models and often contain errors because of lack of testing. This was evident with the Maroochydore Road Interchange Upgrade. After corrections had been made to the Excel-based model, the BCR of project option 6 fell from 4 to 2.1 and the BCR of project option 6A fell from 3.8 to 1.5 (TMR 2015b). The use of customised models usually reduces the transparency of the CBA, as there is less available documentation to verify how the model operates.

4. INCOMPLETE INFORMATION AND DATA

Perfect information is never available for any project. Assumptions are nearly always required to the fill the gaps in data. These gaps can be filled using a variety of approaches many of these approaches are defensible but even defensible approaches can potentially produce quite different results.

4.1. Maroochydore Road Interchange Revisited Again

The Maroochydore Road Interchange Upgrade discussed earlier in this paper is revisited in respect to the treatment of incomplete information and data. Traffic modelling for the project provided data for 2021 and 2031 (Aurecon 2015). Project options 6 and 6A were assumed to be commissioned in 2024. Benefits were calculated for 2021 and 2031 using the traffic data provided. From 2024 to 2030, benefits were interpolated using the 2021 and 2031 data. For project options 6 and 6A, benefits were extrapolated from 2031 to 2054, and were assumed to decrease by 20% per year from the previous year. For the ‘do minimum’ option, benefits were not calculated beyond 2031.

For the final three quarters of the evaluation period, benefits were calculated based on an assumption that could not be supported by traffic modelling. A conservative approach would have been to include benefits up until 2031 and calculate a residual value (for example, using the linear depreciation method) for the remaining 23 years of asset life; this approach would have reduced the BCRs of project options 6 and 6A to 0.9 and 0.8 respectively (TMR 2015b). Another approach would have been to assume the benefits remained constant for the remaining 23 years; this would have improved the BCRs of project options 6 and 6A to 4.1 and 3.8 respectively. An additional year of traffic modelling, for example in 2041, would have greatly improved the accuracy of the CBA.

5. USER BEHAVIOUR

The impact a project has on user behaviour is difficult to predict, yet it can be critical to the success of a project. For example, a new rail line that attracts a large number of new users will be considered more successful than one that does not. Attracting new users may not necessarily always be a good thing. For road projects, that reduce congestion by increasing capacity, new users (induced demand) may cause the road to reach saturation quickly with minimal improvement to traffic flows. Davies (2015) demonstrated mathematically that a road project that creates a 25% increase in traffic volume in the first year of operation could produce as little as 25% of the benefits had the project not induced any additional traffic.

Events that cause disruptions to the transport network will also alter user behaviour. User behaviour altered by events should be easier to forecast as historical data can be used to make predictions. Historical data regarding user behaviour are less likely to be available for a project than an event, as changes in user behaviour for an event is observable in the base case. In Queensland, flood events are very common and often disrupt the network causing changes in road user behaviour. During a flood event, road users are assumed to wait, divert, or not travel (TMR 2011). For projects located in rural Queensland, data regarding road user behaviour during closures are generally not readily available. Analysts are required to make assumptions regarding road user behaviour during flood related road closure events.

5.1. Haughton River Floodplain

The Haughton River Floodplain Upgrade is an example of a project for which the CBA result depended heavily on the assumed behaviour of road users during a flood event. Haughton River is located between Bowen and Townsville along the Bruce Highway (TMR 2015c). The flooding of the Haughton River results in short but frequent closures of the Bruce Highway. As part of the CBA, road user behaviour during flood events needed to be predicted. When the CBA was conducted, there was no guidance to how such assumptions should be made. Davies (2011) recommended assuming road users will select the least costly course of action for each flood event2 . This approach was adopted in the CBA. The different closure times during each flood event triggered different road user behaviour.

In the 2015 CBA report, at a discount rate of 7%, the BCR for the Haughton River Floodplain Upgrade was 0.15. If the Davies approach had not been adopted, road user behaviour per an average flood event would have been considered instead of road user behaviour for each type of flood event. The average duration of closure (ADC) at the project site was 28 hours. To avoid the closure, vehicles would be required to divert and travel an additional 399km. A simple but reasonable assumption would be to assume that road users would rather travel the 399km rather than wait more than a day to travel. If these assumptions were applied, at a discount rate of 7%, the BCR for the Haughton River Floodplain Upgrade would have been 0.33. The value of the benefits calculated using this simplified approach are more than twice the value of the benefits presented in the CBA report.

6. FORECAST DEMAND (TRAFFIC GROWTH RATES)

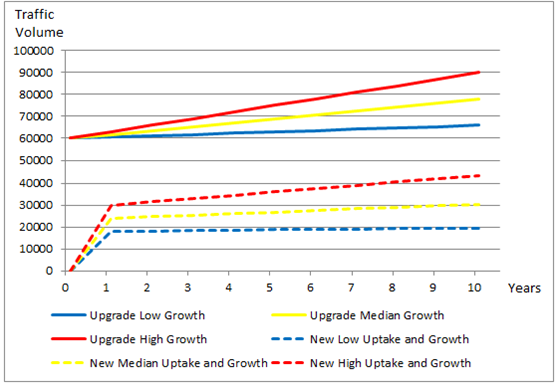

In the context of transport and road projects, traffic growth rates determine the forecast demand for projects. Traffic growth rates tend to fluctuate annually making any forecasts unlikely to be reliable. Sensitivity analysis is typically used to address this problem. CBAs are conducted using the expected traffic growth rate as well as a forecast low growth rate and a forecast high growth rate. For most upgrade projects, the results of the CBA do not vary greatly with the demand forecasts, because, at least at high discount rates (e.g. 7%) the discounting effect reduces the impact of higher or lower demand later in the analysis. The use of sensitivity analysis becomes less effective for new infrastructure or projects relating to new infrastructure. For upgraded infrastructure, there is existing data; therefore, future demand does not depend purely on forecast growth. For new infrastructure, there is no existing data; future demand relies on diverted or induced traffic and forecast traffic growth rates derived from the diverted or induced traffic. Figure 2 illustrates, using a hypothetical example, the effect that high and low forecast demand could have on upgraded and new infrastructure.

Figure 2: Forecasting Project Demand using Traffic Growth Rates

In Figure 2, for both new and upgraded infrastructure, low traffic growth is 1% linear per year, medium traffic growth is 3% linear per year, and high traffic growth is 5% linear per year. For the new infrastructure, low traffic uptake has been assumed 30%, medium traffic uptake has been assumed 40%, and high traffic uptake has been assumed 50% of the traffic volume on the existing infrastructure. In Year 10, for the upgraded infrastructure, the traffic volume that has experienced high growth is 36% higher than the traffic volume that has experienced low growth. In Year 10, for the new infrastructure, the traffic volume that has experienced high growth is 121% higher than the traffic volume that has experienced low growth. The variation in future traffic volumes for new infrastructure is likely to cause wide fluctuations in projected benefits.

6.1. Gracemere Overpass

Gracemere Overpass is an example of new infrastructure designed to cater for traffic demand to the proposed Gracemere industrial estate as well as provide vehicles with safer access to Gracemere (TMR 2011b). Gracemere is located west of Rockhampton. The Gracemere Overpass CBA relied very heavily on traffic forecasts. At the time of the CBA, only a few hundred vehicles accessed the industrial precinct. In the following 10 years, traffic volumes were forecast to exceed 4,000 vehicles and in 20 years, traffic volumes were forecast to exceed 11,000 vehicles.

In the 2011 CBA report, at a discount rate of 6%, the BCR was 1.08. According to the sensitivity analysis, if the traffic growth were half of the forecast value, at a discount rate of 6%, the BCR would have been 0.54. The Gracemere Overpass was opened in 2013 (Gracemere Industry 2013). An ex-post evaluation of the project should be conducted in 2023 to assess the accuracy of the 2011 projections.

6.2. Cooroy to Curra Upgrade (Section B) Ex-post CBA

The BITRE and TMR conducted an ex-post evaluation of the Cooroy to Curra Upgrade (Section B) located on the Bruce Highway, south of Gympie. The Cooroy to Curra Upgrade (Section B) is the first stage of the four stages of upgrading the Bruce Highway between Cooroy and Curra. The project involved realigning and duplicating the Bruce Highway. The extra capacity was intended to reduce congestion on the Bruce Highway. The realignment and the dual carriageway were intended to improve safety (BITRE 2016). The ex-post CBA corrected errors in the ex-ante CBA as well as compared the data available at the time of the CBA to the actual data available at the time of the ex-post CBA. The updated traffic forecasts indicated the following changes:

• a reduction in the initial traffic volume from 16,000 vehicles per day to 14,736 vehicles per day

• a reduction in the assumed growth rate from 3% to 2.17% per annum (linear)

• an increase in the share of commercial vehicles from 15% to 27%

• a reduction in the bus share from 3% to 1%.

Prior to the updated forecasts, at a discount of 4%, the BCR was 2.67. After the forecasts were updated, at a discount of 4%, the BCR was 1.58. Net benefits dropped by almost $300 million, even though the ex-post traffic volume was only 8% lower in Year 1 and the ex-post traffic growth rate was only 0.83 percentage points less. The slightly lower traffic volume and growth rate prevented the volume capacity ratio (VCR) reaching one3 in the earlier years; therefore, in the ex-post CBA, the high costs of congestion were reduced. The ex-post CBA revealed that even apparently minor changes in inputs might significantly alter the results of a CBA under certain circumstances.

7. SUMMARY OF PROJECTS

This paper has investigated a number of transport and road infrastructure projects. These projects include bridge upgrades, intersection upgrades, flood immunity projects, transitway projects, and safety projects. The BCRs of these projects fluctuate depending on the assumptions applied to the CBA. Table 1 summarises the results and the assumptions considered for each project.

Table 1: Summary of BCRs

Projects| Reviewed Assumptions | Low BCR | High BCR

| Arnot Creek Bridge | Base case interventions | 0.75 | 98.26

| Coomera Interchange | Transport modelling | 0.10 | 2.10

| Cooroy to Curra (Section B) | Demand forecasts | 1.58 | 2.67

| Gracemere Overpass | Demand forecasts | 0.54 | 1.08

| Haughton Floodplain | Road user behaviour | 0.15 | 0.33

| Maroochydore Road Interchange | Base case definition | 4.00 | 4.80

| Economic modelling | 2.10 | 4.00

| Incomplete information | 0.90 | 4.80

| Transitways (Eastern & Northern)4 | Transport models | 1.43 | 3.60 |

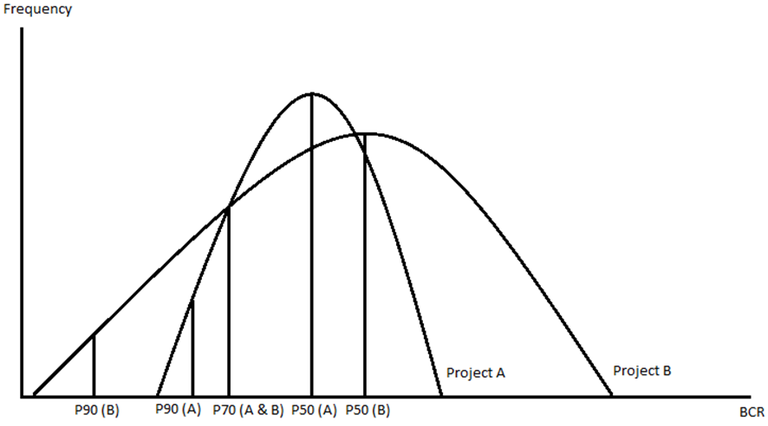

If the projects in Table 1 were competing with each other for funding and prioritisation was determined based on the BCR, the outcome of the prioritisation process would change dramatically depending on the assumptions applied to the CBA. Arnot Creek Bridge Upgrade could rank highest or second lowest. Coomera Interchange Upgrade could rank highest or lowest. Cooroy to Curra Upgrade (Section B) could rank highest or third lowest. Maroochydore Road Interchange Upgrade could rank highest or second lowest. These case studies demonstrate the weakness of prioritising projects using CBA when the application of assumptions is not consistent across projects. 8. SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS AND MONTE CARLO SIMULATIONSensitivity analysis has been applied to most of the case studies discussed in this paper. Sensitivity analysis is useful for determining the range of results for a CBA. Sensitivity analysis is less valuable to decision-makers when there is a wide distribution of results. Monte Carlo simulation could appeal as a solution to the problems described in the case studies and was initially considered a viable approach for this paper. Monte Carlo simulation takes sensitivity analysis a step further with the assignment of probabilities to assumptions to produce distributions of results. The application of Monte Carlo simulation would better inform decision-makers regarding risks involved with realising estimated benefits. The application of Monte Carlo simulation requires analysts to put more rigour into the selection of assumptions to be applied to a CBA. Many of the problems raised in the case studies are not likely to be addressed using Monte Carlo simulation. A consistent application of Monte Carlo simulation is still required if projects are to be compared. The approach to assigning probabilities to assumptions needs to be consistent across projects for valid comparisons to be made. Incorporating Monte Carlo simulation into CBA might not provide a clear-cut approach to ranking projects. Should projects be ranked at the P50 (median) BCR, the P70 BCR, or even the P90 BCR? 5 Figure 3 elaborates on this dilemma. Figure 3: Forecasting Project Demand using Traffic Growth Rates

In Figure 3, Project B has the higher P50 BCR, Project A has the higher P90 BCR, and both projects have the same P70 BCR. Which project should be prioritised? Given the above-mentioned difficulties with Monte Carlo simulation, another approach has been recommended in this paper. 9. PROPOSED SOLUTIONThe identified problems of applying assumptions to projects in this paper appear diverse and difficult to remedy. The existing guidelines do a good job of outlining the key concepts required to conduct a robust CBA. However, these guidelines cannot cover every possible nuance of every project. Hence, assumptions will always be required. A simple solution that would address most of the problems identified in the case studies presented in this paper would be to evaluate projects as part of a program. ‘A program is a group of projects managed in a coordinated way to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually’ (Duncan 1996). Programs allow for greater consistency between projects within the program. A well-documented and reported program evaluation can improve transparency around project selection. Programs consisting of projects in close proximity are most likely to be more effective at addressing the problems outlined in this paper. For example, population growth forecasts and base case assumptions can be consistently applied to the CBAs of projects within the same program. 9.1. The Use of Different ModelsThe appropriate models to be applied across all projects can be determined at the program level rather than at the individual project level. This will reduce bias created by different modelling techniques. Projects can be more easily compared if the models and assumptions used in the analysis are consistent. Including the Eastern and Northern Transitways in the same program would have resolved the problem of inconsistent modelling scopes. Economic models developed for a program are also more likely to produce accurate results because of increased testing and usage. Even if the models still contain errors, the errors will be consistent across projects. 9.2. Incomplete Information and DataIncomplete information and data is still likely to exist for projects within a program but general rules can be applied across all projects. These rules will improve the consistency of the approach to incomplete information. The high level of subjectivity regarding the treatment of the remaining 23 years for the Maroochydore Road Interchange Upgrade is less of a problem if the same approach to extrapolation of data is applied to other projects. 9.3. User BehaviourThe use of programs can help analysts understand the relationship between projects as well as gain a broader view of the influences on user behaviour. User behaviour should also be easier to explain if the projects can be linked using overlapping data sets. For example, a program that includes a railway upgrade and a nearby intersection upgrade that is expected to improve traffic access to the train station. The railway upgrade will attract more users. These users will also use the upgraded intersection to access the train station. Such information regarding user behaviour could be ignored if the intersection was not included in the same program as the railway upgrade. Even if changes in user behaviour do not occur across projects, consistency regarding the treatment of user behaviour will improve. 9.4. Forecast DemandDemand forecasts for projects in close proximity should be closely related. Therefore, consistent assumptions regarding demand will enable projects to be compared with each other even if the demand forecasts are not accurate. The Gracemere Overpass Upgrade could have been included in a program, which included the industrial development of Gracemere. The timing of the overpass could have been aligned more closely with the development of the proposed industrial precincts. 9.5. Base Case AssumptionsImproving base case assumptions is one of the most difficult and most important areas that need improving in cost benefit analysis. Incorporating projects into a program is not necessarily a quick fix for improving the accuracy of the base case. Considering projects within a program is likely to improve the thought process around outcomes that will occur if some of the projects are not included in the program. For example, if the Arnot Bridge Upgrade and the Ingham to Cardwell deviation were in the same program, the base case of Arnot Bridge Upgrade could have been defined with much greater certainty. 9.6. Other Advantages of Adopting a Program ApproachIn addition to offering solutions to the problems identified in this paper, the adoption of a program approach offers many other advantages. According to Davies (2012), the advantages of a program approach are as follows: • benefits and costs of interdependent projects can be easily identified, evaluated, and apportioned to projects 9.7. Limitations of Adopting a Program ApproachA program approach addresses many of the problems outlined in this paper and has numerous other advantages but the program approach is not always a practical solution. There are a number of factors, which make transitioning to a program approach unattractive to agencies. Programs are likely to require a high budget. Funding may not be available to start a program from scratch considering existing commitments. A possible approach could involve putting together existing projects into a program. This approach could introduce and magnify the problems highlighted in this paper, as the program places projects with BCRs calculated in inconsistent ways in direct comparison with each other. The Bruce Highway Action Plan (BHAP) included projects that had been evaluated prior to the formation of BHAP and these projects were proposed to be put in direct comparison with projects evaluated as part of BHAP. The economics team involved in that exercise drew attention to the dangers of making such comparisons (TMR 2013). To adopt a program approach involves a paradigm shift from the existing stand-alone project approach. Such a shift can be difficult. Departments may need reorganising to cater for program teams. Specialist staff will need to be hired. Heads of departments and Government will need to be in support of establishing programs. Greater communication between departments is also likely to be necessary. If these initial transition problems are overcome, programs might not be successful until the departments become sufficiently experienced in program management techniques. Fortunately, courses such as managing successful programs (MSP) can help departments acquire the necessary in-house skills to transition to a program approach. Not all projects are suitable for inclusion in a program. Projects that require immediate attention should not be included in a program, if it will delay implementation of the project. Projects that should stand-alone should not be placed in a program for the sake of an adopted program approach. Appropriate project inclusion should not be a problem if the program places more emphasis on achieving outcomes than project outputs. All projects included in a program should have a role in achieving the programs objectives. There should be some expectation that the portfolio will contain projects and programs rather than just one or the other. 10. CONCLUSIONAssumptions can play a pivotal role in influencing the results of a project. The case studies presented in this paper demonstrate that results can vary significantly even when the guidelines are followed and the assumptions made can be defended with the information available at the time. The variations in results pose the biggest problem when projects are compared with each other. Different project teams have different interpretations of the information available and therefore make different assumptions. In many of the case studies, the assumptions made were not erroneous but resulted from different thought processes and technical advice. The paper acknowledges that assumptions will always have to be made, as information and data will never be complete. The paper also acknowledges that harmonizing the approach applied to developing assumptions is rarely practical, hence comparing projects using CBA will never be ideal. The paper claims that current difficulties with inconsistencies can be remedied to a certain extent using a program approach instead of the current status quo of considering projects in isolation. The paper briefly outlines the advantages of evaluating projects in programs. The paper revisits the problems identified in the case studies and explains how a program approach would resolve or mitigate these problems. The biggest advantage a program offers to mitigate the negative effect of the identified problems is the opportunity to improve consistency in the treatment of assumptions. It is easier to achieve consistency between project CBAs using a program approach than if projects are initially considered in isolation and then compared later. Projects within a well-organised program contribute to supporting the objectives of the program, therefore assumptions should run throughout the program. Assumptions applied to a program are less likely to be spurious as they are given greater consideration through consistent application throughout the program. The approach of determining assumptions between programs is still likely to be different. This paper does not recommend that projects in different programs be directly compared with each other. Adopting a program approach will not require current guidelines to be modified to address the consistent use of assumptions. In fact, less guidance might be preferred, as too much guidance could stifle creativity and innovation (Srinivasan and Kurey 2014). END NOTES

REFERENCESAurecon, (2015), Bruce Highway Maroochydore Road Interchange Project (BHMIP) Economic Analysis – Final Report, Aurecon Australia Pty Ltd Australian Transport Council, (2006) National Guidelines for Transport Systems Management in Australia, 3: Appraisal of Initiatives, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Austroads (2005), Economic Evaluation of Road Investment Proposals: Harmonisation of Non-urban Road User Cost methods, Austroads, AP-R264/05 Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE), (2016), Ex-post Costs-Benefit Analysis of Road Projects Case Study 1: Bruce Highway Upgrade – Cooroy to Curra Section B, Unpublished Draft Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics (BTRE), (2007), Estimating urban traffic and congestion cost trends for Australian cities, Working paper 71, Canberra ACT. Civil Aviation Safety Authority, (2007), Cost Benefit Analysis Methodology Procedures Manual, Australian Government. Cooper Energy (2016), P50 (and P90, Mean, Expected and P10), Cooper Energy, available at: www.cooperenergy.com.au, accessed on: 25/04/2016. Duncan, W. R., (1996), A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Project Management Institute, USA. Davies, W., (2015), What Effect do Queensland’s Major Road Infrastructure have on Traffic Volumes and Growth Rates? Australasian Transport Research Forum 2015. Davies, W., (2012), Road Program Evaluation: Assessing the Bigger Picture, 25th ARRB Conference. Davies, W., (2011), Advance Methods of Evaluating benefits from Improved Flood Immunity in Queensland, Australasian Transport Research Forum 2011. Department of Treasury and Finance, (2013), Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines, Victorian Government, Melbourne. Gracemere Industry, (2013), Gracemere Overpass Open, Gracemere Industry, available at: https://gracemereindustry.com/2013/05/25/gracemere-overpass-open/, accessed on 11/04/2016. Main Roads, (2008a), Benefit Cost Analysis Coomera Exit 54 Pacific Motorway – Project No. 160/12A/20 (August), Queensland Government. Main Roads, (2008b), Benefit Cost Analysis Coomera Exit 54 Pacific Motorway – Project No. 160/12A/20 (November), Queensland Government. Office of the Infrastructure Coordinator, (2013), 2012-2013 Assessment Brief (Brisbane Transit Ways), available at: http://infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/projects/project-assessments.aspx, accessed on 12/04/2016 National Guidelines for Transport System Management (NGTSM), (2016), Cost Benefit Analysis, Transport and Infrastructure Council Sinclair Knights Merz (SKM), (2009), Cost-Benefit Analysis Coomera Interchange Exit 54 (Stage 1A) – CBA Report, Queensland Government. Srinivasan, A., and Kurey, B., (2014), Creating a Culture of Quality, Harvard Business Review, April 2014. Transport and Main Roads, (2015a), Cost Benefit Analysis Summary – Arnot Bridge Upgrade, Queensland Government. Transport and Main Roads, (2015b), Aurecon Economic Model Options All P90 V14 07 03 2015_WMD(2), Release Version – 244418 Aurecon Australia Pty Ltd Transport and Main Roads, (2015c), Cost Benefit Analysis Report – Options Analysis of Haughton River Floodplain, Queensland Government. Transport and Main Roads, (2014a), Cost Benefit Analysis Report – Northern Transitway, Queensland Government. Transport and Main Roads, (2014b), Cost Benefit Analysis Report – Eastern Transitway, Queensland Government. Transport and Main Roads, (2013), Bruce Highway Action Plan Economic Evaluation, Queensland Government. Transport and Main Roads, (2011a), Cost-benefit Analysis Manual – Road Projects, Queensland Government. Transport and Main Roads, (2011b), Benefit Cost Analysis – Gracemere Industrial Access Project, Queensland Government. Transport, Roads and Maritime Services, (2013), Traffic Modelling Guidelines, NSW Government. Tveter, E., (2013), Dealing with the base case in cost benefit analysis, European Transport Conference 2013. |

|---|