“Whether a particular human being or god "actually" existed and "actually" experienced all the symbolic events of a myth is of no consequence for the mythically operative consciousness of people living at the vitalistic stage of culture.” (Dane Rudhyar in The Magic of Tone and the Art of Music)

Looking at The Da Vinci Code phenomenon as a whole in retrospect, it may seem like a business plan of exceptional brilliance: do some Googling, collect conspiracy theories and outrageous ideas, which you know would make religious folk protest; write a book. If you succeed in getting enough attention, your novel might become a movie. Almost twenty years after it was first published, the novel has sold over 80 million copies, and the film has long been the highest grossing movie for its director Ron Howard, who had previously directed blockbusters Apollo 13 and A Beautiful Mind. Earlier this year Tom Hanks, who portrays a Harward University professor named Robert Langdon – art and symbology expert in all the films based on Dan Brown’s books, apparently had pointed out to The New York Times that at the time The Da Vinci Code was a “good commerce”. Meaning lots of money. But was it an easy money?

I don’t have Dan Brown here to ask about how easy it was to write The Da Vinci Code, but what I do know is that the Internet was still very young at the time (barely into the age of Web 2.0, and it was all before the era of social networks) thus in order to do the research and come up with a coherent chain of little known speculations regarding the roots of Christianity, one would have had to pay visits to more than one or two libraries and archives, and have to turn to hard to find friends, who’d have keen and scholarly interest in the matter.

When I went to see the film’s premiere at the local movie theatre, the religious people handing out leaflets with explanations about what is not right with The Da Vinci Code’s story only further confirmed my beliefs that the material in it was consequential; explosive even. I hadn’t read the novel at the time, and some promotional info about the film prior to its release made me feel like it’s nothing I’ve ever seen or heard before. As much as any clergyman would have likely told me that there’s nothing in the story that’s not been known and available to everyone for centuries, I am still of opinion that an average person in a predominantly Christian country, and beyond it, wasn’t aware of any of what both, the novel and the film tell us regarding religion. The Da Vinci Code opened door to a whole different side of Christianity. It had a revolutionary effect for an average mind at the time. It was a proof that there’s still a lot we don’t know about things we thought were all known and clear, boosting the spirit of questioning and searching in anyone, who wouldn’t be content with approach to knowledge in line with some doctrinal faith. I think there indeed was a good reason, why the film got banned in so many countries upon and after its release.

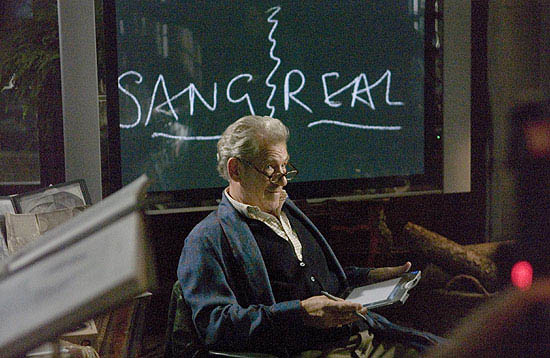

Ian McKellen in The Da Vinci Code movie. Source

Today the novelty of all of the above in my consciousness has long since worn off, and lets me watch the film with a lot less bias than what it was for me back in the noughties, when it was one of my favourite movies for its theme alone. Yet, while the feeling of watching something previously censored is not there anymore, it is still a thrilling watch every now and then, and that’s because it is designed to be a quest and a head spinning roller coaster ride through Paris, London and Roslin village in Scotland. The promise of so many wondrous things, hidden by centuries old buildings, that can be seen only if you know where to look has still got that exhilarating effect on me, same as it was more than fifteen years ago. This is probably the reason why I don’t mind the role Tom Hanks plays in it being not among his more impressive ones. While he obviously gets a lot of screen time as an actor playing one of the lead characters, he is however supposed to be an academic, who keeps it cool and relies on logic and reason at all times. Yet it is still, in my opinion, very well played if we consider that the man, who has spent most of his time studying and researching, had suddenly been thrown into a far more dangerous and life threatening research than anything he’d been used to up to that point. There is nearly nothing about Langdon as a person in The Da Vinci Code except his professional persona. Almost as if Robert Langdon never had a life other than the professional one. What little other aspects of his character are shown to the viewer during his interaction with Ian McKellen’s Sir Leigh Teabing – a historian and expert in everything that has to do with the Holy Grail, is barely noticeable; such as the love for intelligent argument being turned into a sports discipline (still a lot of an academic in that one). This characteristic is probably why Sir Teabing subjects Langdon to a quiz before letting the latter, along with his companion, pass through the former’s house gate. That quiz is indeed one of the most memorable scenes for me in The Da Vinci Code, which basically introduces McKellen’s character in a brilliant way while shimmering with a light of intelligent humour; also, the cup of tea shouldn't be left without a mention here.

Ian McKellen brings to his role a notable spirit of enthusiasm (which at times takes delightfully darker form), which Tom Hanks seems to rarely be allowed to match because, once again, he never ceases to be an academic. This aspect however helps another of the lead characters – police cryptographer Sophie Neveu. With her grandfather Jacques Saunière, a Louvre Museum curator, having been murdered in most mysterious and cryptic circumstances, Sophie has a lot going on, which, as the film ramps up its pace, puts a lot of stress of quick decision making on her. The actress Audrey Tautou cuts through all of it with dynamism, with her background and personality shining through in every single scene. The interplay between the two – Hanks and Tautou, is, in my view, one of the strongest parts of the film, which, I’d say, very much depended on this particular aspect.

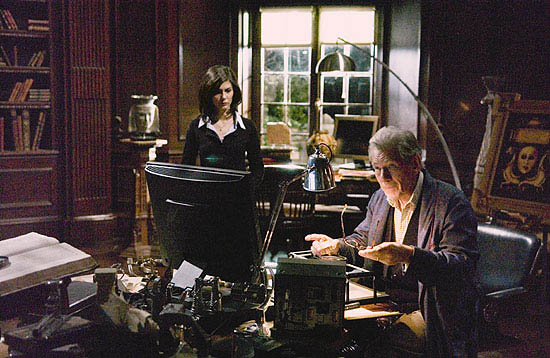

Tom Hanks and Audrey Tautou in the promotional still of The Da Vinci Code movie. Source

An interesting pinnacle in the movie, in my opinion, is the scene in Leigh Teabing’s private plane, where Sophie finally gets to confront one of the story’s antagonists (the story deals with the concept of antagonist in an unusual and interesting fashion) named Silas, who is a self-flagellating Catholic monk. Essentially it is a moment of clash between doctrinal faith (Silas) and its challenger (Neveu, who’s part in the story at that point has gone way beyond being a cryptographer), and is played out as such. Silas is embodied by Paul Bettany, who delivers spectacular performance of a psychologically and physically extremely tortured person. Silas looks like someone who’s found in his lifestyle the last resort of making sense of his very existence. All this had been brought to life by Bettany, Howard and make-up artists in a very convincing manner; the character is one of the most memorable adversaries I’ve ever seen in a film.

Audrey Tautou and Ian McKellen in The Da Vinci Code movie. Source

The elephant in the room had always been the fact that right from the beginning of Christianity it had been a boys club. Works like The Da Vinci Code point right at the obvious lack of gender representation, when it comes to core tenets of the religion in question: the gender of apostles, the gender of the authors of all the canonical Bible books; bishops, patriarchs. It can be argued that at times it all had resulted in persecution on the basis of gender. In light of all that The Da Vinci Code, in my view, makes for an important test as to how okay it is to question beliefs at the foundation of those tenets.

Read my review of a movie Under the Silver Lake, featuring a different kind of quest here.

Read my review of Deadwax tv series, which deals with another quest here.