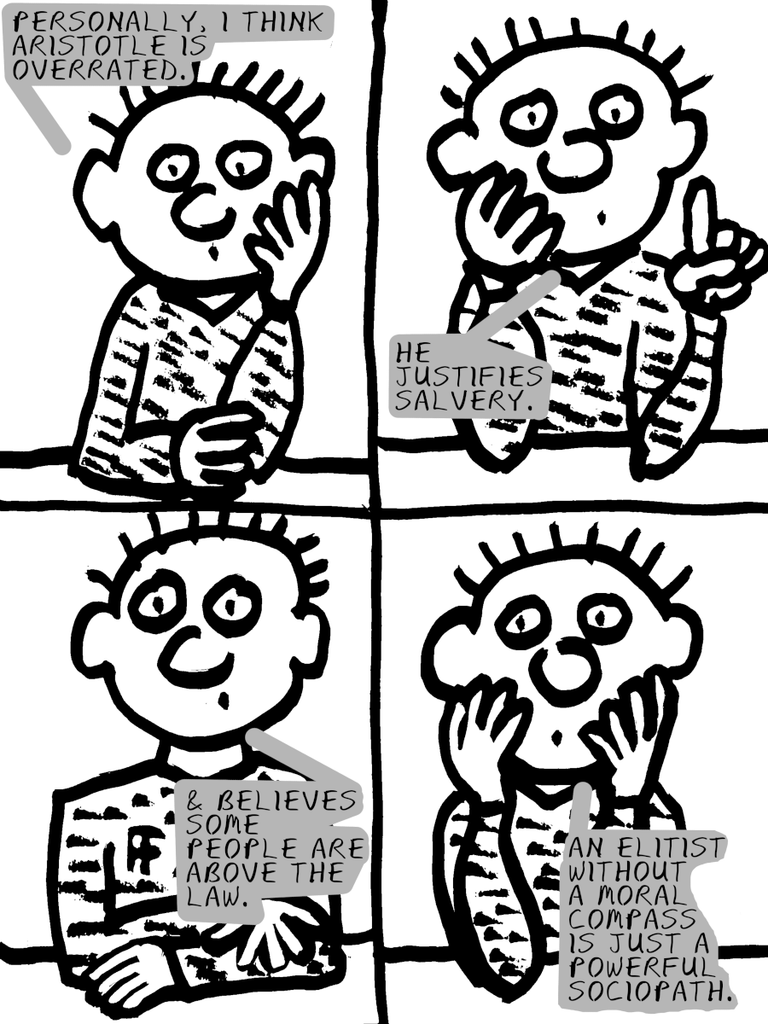

Aristotle on Slavery

In his work Politics, Aristotle justified slavery by arguing that some people are natural slaves, while others are slaves solely by law or convention.

According to Aristotle, a natural slave is someone who, while being human, is by nature not his own but of someone else, and he defines natural slavery in two phases: the natural slave's existence and characteristics, and the natural slave in society and in interaction with their master. Aristotle believed that natural slaves were slaves because their souls weren't complete, lacking certain qualities like the ability to think properly, and therefore needed to have masters to tell them what to do.

Aristotle's justification of slavery was used by antebellum proponents of slavery in the United States to give their own arguments more credibility. However, these proponents often distorted Aristotle's philosophy to fit their own worldview and racial biases.

Aristotle himself did not factor skin color into his discussion of slavery, although he did point to specific ethnic groups that he considered more likely to function as natural slaves.

Aristotle also argued that slavery was beneficial for both the masters and the slaves. He believed that slaves provided the leisure necessary for the welfare of the state and that being a slave allowed the enslaved person to share the virtues of the master and elevate themselves.

However, critics argue that Aristotle's classification of individuals on the basis of capacities is flawed, and his theory is prejudicial and contradictory to human dignity.

Aristotle's views on slavery have been widely discussed and criticized, with many scholars arguing that his justification of slavery is fundamentally flawed and prejudiced.

Aristotle's views on and the potential for some individuals to be above the law are nuanced. He generally advocated for the rule of law, emphasizing that laws should govern rather than any one individual. In his Politics, Aristotle wrote, "It is more proper that law should govern than any one of the citizens: upon the same principle, if it is advantageous to place the supreme power in some particular persons, they should be appointed to be only guardians, and the servants of the laws".

However, Aristotle did recognize certain exceptions. He acknowledged that in some cases, particularly those that are highly complex or unique, the application of general laws might be insufficient. In such instances, he believed that the judgment of particular individuals, who could apply equity (epieikeia), might be necessary. Aristotle stated that while laws are laid down in general terms and are made after long consideration, some cases are so fraught with difficulty that they cannot be handled by general rules and require the focused insight of particular judges.

Despite this, Aristotle maintained that these exceptional cases should be kept to a minimum and that legal training and institutions should continue to play a role in their disposition. He did not advocate for a wholesale exemption of individuals from the law but rather for a system where the law is the primary governing force, with limited and carefully controlled exceptions.

In summary, while Aristotle generally supported the rule of law, he recognized the need for flexibility in exceptional cases, where the application of equity by skilled judges might be necessary. However, he did not justify a broad or systematic exemption of individuals from the law.

**

The word "epieikeia" originates from the Ancient Greek ἐπιεικεία, which means "equity" or "fairness," and is derived from the adjective ἐπιεικής (epieikēs), meaning "fair" or "reasonable."

Synonyms of "epieikeia" include equity, fairness, and reasonableness.

Antonyms of "epieikeia" include inequity, unfairness, and unreasonableness.