When I got my first-ever internship, I remember one of my supervisors bought me my first toolbox, which was a very nice gesture. But it was at that moment that reality kicked in - I had to learn how to use those tools with relevance to my role. I was just a typical graduate who had never used tools to troubleshoot any solar-powered equipment besides using some screwdrivers and spanners mostly for DIY. Although I was trained to be a user of the output from some of the instruments, the university practicals never really prepared me to deal with real-world events.

We always had technicians who were responsible for instrument maintenance at University. But now I had to not only be a data user but also troubleshoot and calibrate the sensors. It felt like a simple learning curve until I was told they were very costly sensors all combined; on average, to set up one complete flux tower station costs roughly 117 900,00 USD excluding maintenance costs. We had three stations to be monitored meaning I had to forget all the motivational speakers' advice that says: "you learn from your mistake". Surely all my family's nett-worth could never afford the costs of the mistakes if I was to negligently mess up sensors in those towers.

Pushing boundaries: Adapting to a changing skill demand

Now that life had landed me this opportunity, I had to step out of my comfort zone and make peace with the reality that my qualification could only get me into the industry. But what mattered going forward was the flexibility of my brain to learn new things and to pair hard work with working smart. I came to realise that people who also invest time in self-learning are better at understanding what they do than those who only earn the skill through passing examinations.

For most of my research journey, I have also come across research assistants (general labourers) who had way more understanding in setting up a scientific experiment relying on concepts they learnt when assisting "qualified" researchers in the fields. It was amazing how I would think of a complex scientific way to do field sampling and they would suggest an efficient way. To me, that is humbling evidence that self-learning and mentorship can be more efficient and it has more practical significance than acing an exam paper.

The circumstances: Sense of belonging in a Job Industry

Pushing through the limits meant I had to learn to brand myself as per industry and not just the qualification. But to avoid the misconception about my competence I settled for the title "a researcher" whose discipline involves collecting and managing a climate-related database. Not to be confused with a weathercaster. This gets tricky because the job market and potential funders always ask the question so what do you bring to the table?

This also takes me out of my comfort zone as now I have to tap into the practicality of making my work meaningful to farmers, environmental management agencies, and climate modellers and had to also make the data useful to those who are interested in AI - training their model to predict the possible outcome in response to climate, water use, crop yields or just simple assessing human impact on the environment.

I can say 80% of the technical work that I do now was not part of my practical and theoretical study at university but it is mostly from self-leaning and receiving mentorship. I did get a fair exposure to the theoretical side of what I do from university syllabi, but the relevance was not that apparent and this made it a lot more intimidating to even apply for my first internship role.

The Outcome: Integrating handwork and working smart

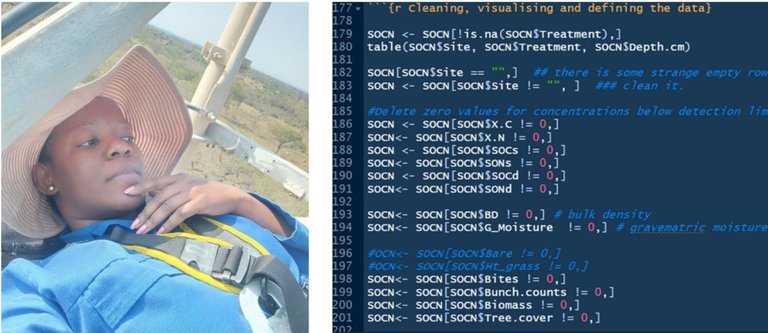

I have realised that learning is a continuous task and much effort still goes into self-learning as the industry keeps upgrading to new versions and improving accuracy with the new technology. Working with a huge dataset also means working smart and automating the processes. I had to learn to code specifically for data management codes as working on excel would not be efficient and is a nightmare for a large dataset.

I think these days the advancement in technology forces us to be out of our comfort zone. Back then, most jobs used to have defined workflow and most tasks were repetitive but now those tasks can easily be done by AI through automation. It is the flexibility of mind to innovation and comprehension that matters now which cannot be replaced by algorithms and exercising that muscle requires more than structured learning. And through this experience, it becomes apparent to me that, those who also invest time in self-learning stand a high chance of pushing more boundaries and to remain irreplaceable as the technology progresses to have robots and AI replace humans in job industries.

All the images used in this post belongs to the author.

Thank you for stopping by!