Book Review:

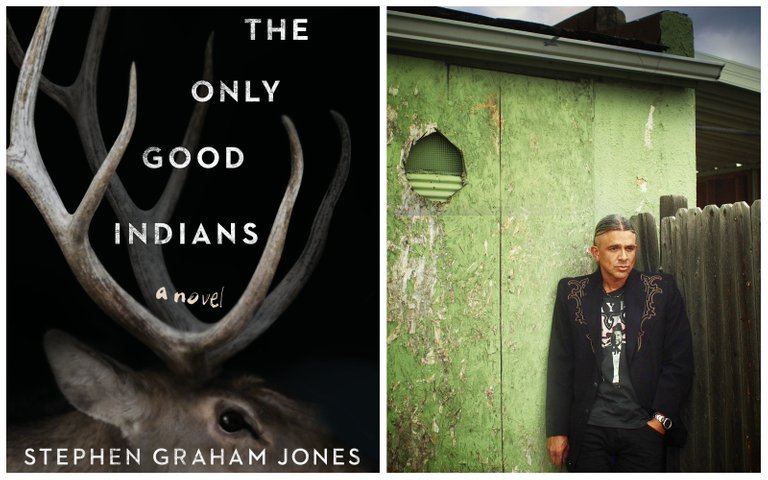

“The Only Good Indians” (2020)

by

Stephen Graham Jones

Hey, fellow Hivers! Been too long since I posted in the Hive Book Club community but I promise I’ve been reading—and plan on doing a whole lot more of it. I’m bad at meditation but the closest thing for me is books, movies, and television shows. I’d include video games in that category but I’ve tossed too many a controller at the wall to consider that activity as calming. Not to say that reading or watching isn’t interactive—you turn the page or flick a tablet screen, you mentally and emotionally invest in people and places and objects might not even be real, investment is interaction. The way video-games are interactive media adds a bit of exhilaration and I think one-way media has a bit as well. When watching a show, a movie, or reading a book, you submit yourself to a series of events you have no say in, a type of emotional and mental Stockholm Syndrome—a physical one too since you usually bolt yourself to one spot and let the story or news or squiggly lines on a piece of paper transport you elsewhere in your mind … Haunting of Hill House! Or was it, Head Full of Ghosts? I was trying to remember what my last Hive Book Club post was. Either the 50s classic by Shirkey Jackson, or that other guy who did Survivor’s Song and the source material for that recent Shymalan cabin movie. Paul Tremble, that’s his name, the author. Had something to do with scared movement. How appropriate for his genre. Anyway, that’s enough intro from me, let’s talk about Stephen Graham Jones’ THE ONLY GOOD INDIANS.

“The Only Good Indian” is a horror book by Stephen Graham Jones, a Blackfoot tribe author who according to his website has written quite a lot of stuff. His most famous being “The Only Good Indians” and a series called “The Indian Lake Trilogy.” I have the first of the series, “My Heart is a Chainsaw” and to be honest other than sort of liking “The Only Good Indians” I think I also got the book because of how metal I thought the title was.

The story follows Ricky, Lewis, Cass, and Gabe: four men from the Blackfoot tribe who, back when they were teenagers, intruded into the elders’ section of their people’s reservation and shot unsuspecting deer that were culturally and legally protected. Despite its group being ambushed and mercilessly mowed down in a hail of rifle-fire, one extea healthy-looking deer managed to keep limping away despite it’s severe injuries. But Ricky, Lewis, Cass, and Gabe shoot it again and then finally execute it with a shot to the head. While gutting their kills, Ricky discovers that the last extra healthy-looking deer was pregnant and, out of pity, buries its unborn baby deep in the nearby earth of the recent massacre, and keeps the skin in the wish to not waste such a sad kill.

Years later, Ricky and Lewis have left the Blackfoot reservation but live dissatisfying lives. One of the first events of the book is a depressed and drunk Ricky upsetting the non-Indian patrons of a bar and being chased out into a parking lot where he struggles to hide as the angry non-Indians hunt him down. He nearly escapes to a grassy field but a herd of deer arrive and block his path, causing him to turn around and laugh before he is beaten to death by the angry bar patrons. It’s one hell of an opener and without the context of what him and his childhood friends did years earlier, it just comes off as a random, strange and violent encounter but by the time we move on to Lewis we begin to notice hints of haunting and deathly encounters related to deer. Dreams, visitations, hallucinations, and finally in the third act of the book—a horrific manifestation related to that last pregnant deer.

The second character Lewis, who’s also left the reservation, is working at the post office while fixing up his motorcyle and living with his non-indian girlfriend. What I found interesting about this particular character was not just how depressed and apathetic he was on the surface but how everyday conversations with co-workers began to grind away at his confidence in his relationship with his girlfriend who is white. On one hand, it is historically accurate that white people took American Indians’ land—but the level of subtle prejudice and distrust for someone so far removed from a devastating ancestral event is a bit fascinating. I can’t remember if the European ancestry of Lewis’s white girlfriend is ever revealed but just the reality of her obvious whiteness created an immediate otherness compared to Lewis and his co-workers, especially a Crow tribe woman he worked with. It was a form of racism that felt all the more tragic because it was toward someone Lewis loved. And it didn’t just come from others but was a constant thought in his head—along the lines of “I love her but it’s impossible for her to ever understand me because she’s not Indian.” It reminded me of the otherness imposed on non-white characters in much older classic literature, that because someone wasn’t European they couldn’t understand or grasp grand concepts like real beauty or real connectedness or logic. But this time, flipped on its head: because Lewis’s girlfriend is of European ancestry she can never understand him—as if she were genetically linked to the original imperials who took Indian land. Maybe, I missed a line but she could be a much newer American than him, maybe from European immigrants arrived in America less than a century ago. But I think the true point of Lewis and his girlfriend’s relationship is that racism works both ways, and it can also be subtle. Is it impossible to be racist against someone you love? Unfortunately, no. Can racism be so gentle and unspoken, that it can be both damaging yet almost undetectable? Yeah. It’s super cliche but true but some of the worse monsters are the people who dehumanize not just strangers but the people they’re closest with. Not respecting their own beliefs, Lewis and his friends soon console themselves with this idea that no one respects beliefs, that there are people with no genuine beliefs, and that if nothing is really true, then long ago they never ever really did anything wrong. In the end, dehumanizing others dehumanizes yourself: a person who views people as monsters, becomes a monster themselves. Maybe it’s a stretch but it feels like the book was also about secretly disrespecting what we claim to love, or already know is lovable and respectable, like close ones and traditions are sacred deer. Lewis, Ricky, Cass, and Gabe hate what’s historically and contemporarily been done to their people and what their people hold dear… but then they themselves go out of their way to encroach on tradition and a holy place to slaughter sacred-animals. The story becomes not just the woes of disrespecting the divine but how it disrespects one’s self. It’s not something specific to just Native Americans but can be said for all people who don’t acknowledge and respect the journey and labor and teachings of all the people who came before them, all the peoples whose blood and sweat were paid to life so that modern people could exist.

I don’t want to spoil the book by saying what ultimately happens to Lewis, Gabe, and Cass. While I enjoyed the book I think the criticisms about the tonal shift of its ending are pretty valid. Jones supposedly writes these stories very quickly which feels miraculous due to how well he sets things up at first but I could definitely feel the story losing a bit of momentum near the end—but nothing that turned it away from being a good story. I still both enjoyed the experience but felt it shied away fron its potential near-perfection, or adjacency to near semi-perfection since that’s such a strong word.

The author Stephen Graham Jones does a great job capturing the interior of these Native American men, the pride and hardships of living on these almost forgotten reservations, the flight of their women and youngsters from these tough and almost forgotten parts of land. I saw the last three characters in their multiple stages and personas in life—as indigenous men, teenagers once, young wayward men, older scarred men, dependable and irresponsible fathers and uncles and boyfriends or husbands, and as ordinary joes despite their supernatural predicament.

A popular horror trope is non-Indians accidentally defacing a sacred indigenous burial ground, or similar site, which triggers a paranormal nightmare—but those scenarios are usually based on ignorance. What kind of horror perspective do you get when the people triggering the nightmare were already knowledgable about it. A lot of times in stories, strangers come to town and ruin life but another likely likelihood is the town cannibalizing itself, its youth losing the knowledge of elders or simply forsaking it—because strangers have broke the rules, so why can’t they? I think Jones does a good job of saying that monsters don’t come to town, that sometimes they’re already there, and that the idea of a town or a community civilizes the monsters into becoming human—but that’s a neverending process, never permanent.

As far as just the overall feel of horror, I genuinely dreaded the seemingly mundane lives and realistic depressive and addict-personalities more then the supernatural horror. The endlessly, mind-numbing small talk between co-workers, and their desperate attempts to feign affection for each other’s families despite having never met. It captures the charade of a group of imprisoned people desperately trying to stave off loneliness. While the book’s best writing goes into describing its unnatural horror, what truly scared me was how believable and realistic the introspection and situations the characters were in during their daily lives. It was refreshing but dreadul to see personalities similar to people I grew up. It was like, “Oh wow, there’s really people exactly like that everywhere.” Humanity painfully corosive in its smallest details and units but also individual personalities are nowhere near as unique as we like to think they are.

In the end, I think I’d rate “The Only Good Indians” a seven out of ten. A great and humanizing depiction of racism in interracial-relationships, and viewpoint into a people from a community that doesn’t often get a solid depiction in popular media, and while the horror elements start off poetic and mesmerizing they in the end dwindle into something rather flat, predictable, and at its worse moments—somehow cartoonish.

7/10

IMAGE SOURCES

Cover photo