Nariz larga

Siempre creí que a mi padre le crecería la nariz; él es muy bueno para inventar historias; de cualquier objeto, circunstancia o lectura inventa su propia ficción. Para entonces yo era una niña, siete años tenía y escuchaba sus ocurrencias con entusiasmo porque me entretenía; era divertido andar con él, pero un día la maestra nos dijo en clase que a los mentirosos les crecía la nariz, que no importaba la mentira que dijeran, que igual era malo.

Desde entonces empecé a vivir con la angustia de que a mi padre se le alargara la nariz como una zanahoria; no imaginaba ver a mi padre con semejante vergüenza, pero lo que más temía era que si eso llegara a suceder los compañeros de clase se burlarían de mí por tener a un papá mentiroso.

De modo que empecé a decirle que ya no me contara cuentos o que lo hiciera, pero sin exagerar, sin mentir. Papá por supuesto que no me hizo caso; al contrario, se las ingeniaba para que las exageraciones fueran terriblemente grande, humorísticas y cautivadoras. Se esforzaba más y yo olvidaba lo que mi maestra me había dicho y a cambio pasaba los momentos más felices de mi niñez.

Pero en clase volvían los temores cuando la maestra machacaba la misma historia. Y así viví un tiempo, angustiada de que a mi padre le creciera su nariz, y alegre porque me seguía contando hermosas historias.

Hasta que un día le conté mis temores, le dije que yo le creía a la maestra porque ellos, mamá y papá, me habían dicho que a los maestros había que creerles. Papá me dijo que sí, que la nariz de él, últimamente, era más larga que una zanahoria; y lo peor, que pesaba mucho. Me dijo que no dijera nada porque, así como yo no veía su enorme y pesada nariz, los otros tampoco la veían; mi nariz, me dijo, es invisible y es del tamaño de una trompa de elefante, de elefante bebé.

Aquel día me pidió que le guardara el secreto de su nariz, y como buena hija le prometí que nadie sabría su verdad. También le dije que si quería no me inventara más historias, pero me respondió que eso nunca dejaría de hacerlo porque, aunque su nariz fuera larga y pesada a él le gustaba así, porque cada centímetro le recordaba uno de los cuentos que a mí me habían hecho reír.

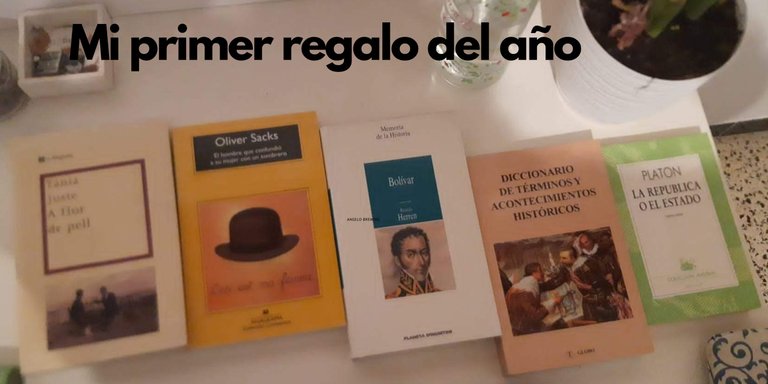

Desde entonces leo, y cuando lo hago es imposible no recordar a mi padre. Hoy mismo me he comprado cinco libros; el de Oliver Sacks, El hombre que confundió a su mujer con un sombrero; Bolívar, de Ricardo Herren; A flor de piel, de Tania Juste; un Diccionario de términos y acontecimientos históricos; y la República, de Platón. Son libros de segunda mano, pero están en buen estado y lo mejor es que la librería me queda cerca de mi casa, aquí en Palma de Mallorca y los precios son accesibles. Ya leí a Oliver Sacks, pero ahora empezaré a releerlo en físico, que es mucho mejor que el libro digital; luego seguiré con A flor de Piel y por último le entraré a Platón. Ahí les contaré cómo me fue con cada uno.

English version

Long nose

I always thought my father would grow a nose; he is very good at making up stories; from any object, circumstance or reading he invents his own fiction. By then I was a little girl, seven years old, and I listened to his witticisms with enthusiasm because it entertained me; it was fun to hang out with him, but one day the teacher told us in class that liars grew noses, that it didn't matter what lie they told, that it was still bad.

Since then I began to live with the anguish that my father's nose would grow as long as a carrot; I could not imagine seeing my father with such an embarrassment, but what I feared most was that if that were to happen, my classmates would make fun of me for having a lying father.

So I started to tell him not to tell me stories anymore or to tell me stories, but without exaggerating, without lying. Dad of course didn't listen to me; on the contrary, he managed to make the exaggerations terribly big, humorous and captivating. He would try harder and I would forget what my teacher had told me and in return I would spend the happiest moments of my childhood.

But in class, my fears would return when the teacher would drone me with the same story. And that's how I lived for a while, anxious that my father's nose wouldn't grow, and happy because my father kept telling me nice stories.

Until one day I told him my fears, I told him that I believed the teacher because they, mom and dad, had told me that teachers should be believed. Dad told me that yes, lately he had a nose longer than a carrot; and what's worse, it was very heavy. He told me not to say anything because, just as I couldn't see his big, heavy nose, others couldn't see it either; my nose, he said, is invisible and the size of an elephant's trunk, a baby elephant's trunk.

That day he asked me to keep the secret of his nose, and as a good daughter I promised him that no one would know his truth. I also told him not to make up any more stories if he wanted to, but Dad replied that he would never stop because, although his nose was long and heavy, he liked it that way, because every centimeter reminded him of one of the stories that had made me laugh.

Since then I read, and when I do it is impossible not to remember my father. Just today I bought five books; Oliver Sacks' The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat; Bolivar, by Ricardo Herren; A flor de piel, by Tania Juste; a Dictionary of Historical Terms and Events; and Plato's Republic. They are second-hand books, but they are in good condition and the best thing is that the bookstore is close to my home, here in Palma de Mallorca, and the prices are affordable. I have already read Oliver Sacks, but now I will start to reread it in physical format, which is much better than the digital book; then I will continue with A flor de Piel and finally I will get into Plato. I'll let you know how I did with each one.