My High School, 1914, the Year It Opened

Credit:Jansi. Public domain.

This post was inspired by @ericvancewalton's Memoir Monday prompt for last week. He invited bloggers to recall their high school days and then he offered questions to guide them through this memory. One of the questions was, Were you popular?

What a peculiar place school can be, that such a question has relevance years later. This experience of being popular/unpopular seems to haunt people into adulthood. Think of the movies inspired by it--Carrie, Heathers, Mean Girls--to name some of the more influential.

The first one, Carrie, is a horror movie. The second, Heathers, results in mayhem--murder, suicide and self demolition. The third, more politically correct, results in social chaos, damaged reputations and a fractured spine. In each film, popularity is toxic.

To address @ericvancewalton's question directly: Was I popular in high school? That is not a question that has a clear answer in my case. For one thing, my school was not co-educational, so the element of being chosen by a boy was removed. In each of the movies mentioned above, being chosen by boys was an important part of the popularity formula.

I think the specter of unpopularity is particularly oppressive for adolescents because when students enter high school, usually at the age of 14, they are at the apogee of their peer pressure vulnerability. The structure of high school exacerbates the natural inclination of teenagers to sort themselves according to the relative value of their peers. Schools organize students in groups and hierarchies.

A case in point: A few weeks after I entered high school the principal called me down and told me I would be a class officer because of my GPA. Before I ever met most of my classmates, I was noticed. That gave me a head start on the peer status ladder.

These things matter to kids. They take their cues from teachers, and from others.

Nothing about me would have predetermined popularity. I didn't care about clothes, or fuss with my hair. I was an oddball, independent and peculiar for sure. But now I had the imprimatur of the school authority. The door was open. I was nominated for something else. Appointed to another position. Soon I was making speeches at school assemblies.

I wasn't popular in the Heather sense. Never could be. Never would be. But I was well-known.

My son reminded me of a movie from the 80's that became a cultural touchstone: The Breakfast Club. This movie is all about social hierarchy and popularity. I didn't relate to the types portrayed, but they resonated with a generation.

Here's a picture of me, circa 1963, engaging in one of my not Healther-like activities: playing clarinet in the orchestra.

I'm grateful school administrators saved me from the dustbin of unpopularity, a place I was surely destined to occupy, but it always irked me that school structure, and teachers, had such a profound effect on a student's social standing.

When I became a teacher (not a career I had planned on pursuing), I was acutely aware of this power to influence opinion and status.

Teachers give cues to students about how to treat those around them. It is often the case that the more popular, socially powerful students, are courted by teachers. It's good to have those students on your side when you're teaching a class. It makes things easier.

Meanwhile, reinforcing the social status of students exaggerates their power.

High school popularity. It all came rushing back to me with @ericvanwalton's question. Those years of imposed cruelty, on so many kids. What a waste. What an empty value system. At the heart of it is fear. Fear of not fitting in, of being left out, of being alone. And with that fear comes control, enormous control.

Students use it. Teachers use it.

The magic of my high school career was, I didn't have fear, not of that. There were a lot of things going on in my life. School was simply something I had to do. And I did as little of it as possible.

Frankly, I don't think school is healthy. I think the whole popularity unpopularity issue is a symptom of its ills. There are other ways to educate children, without locking them into tightly organized, regulated structures.

Marie Curie, for example, dreaded sending her daughters into a traditional school. She organized a school cooperative with her colleagues who also had children. They all took turns teaching the kids in loosely organized groups. The children would travel from one place to the other for their lessons. These lessons were punctuated with nature trips.

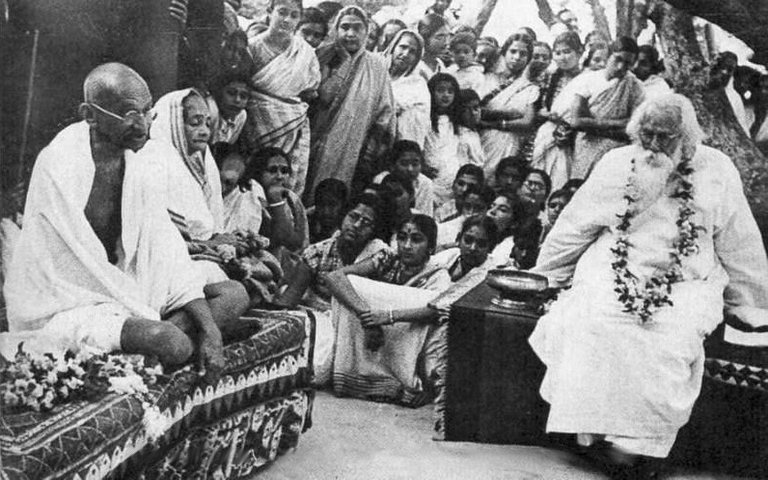

Tagore and Gandhi at Santiniketan, Tagore's School. 1940

Credit: Unknown author. Public domain.

Or, alternately, how about Rabindranath Tagore? His concept of open school is still practiced in India today. He believed in emphasizing the interest of the individual. Preferably, classes would be held outdoors, and children could take nature breaks when they were inclined. Children sat on mats and were encouraged to explore their ideas through the arts.

I can't imagine popularity or unpopularity being an issue in the Tagore or Curie school.

Children need to be educated. Home schooling is not necessarily the best course for many children. Most parents don't have the skill or time to impart a truly quality education. And, isolating kids from their peers may not be a good idea. Still, I do understand the temptation to avoid the traditionally structured school model.

Basically, I hated school before high school, and during high school I found it barely tolerable. To me it was a prison (check out the picture at the top of the blog...doesn't it look like a prison?). School was an imposed sentence, and a lot of time thrown away unproductively. Study hall? Hygiene? Huge blocks of space that ballooned the day.

As the movies cited in this blog suggest, school is not a good experience for millions of kids. Popular, unpopular? Just one of the serious issues with the institution. Surely, there is a better way.