Credit: arian.suresh from Chennai, India.CC Attribution share-alike license 2.0

If you come across the beetle pictured above in your garden--or one of its cousins--do not pick it up. While sometimes this beetle may be handled safely, should it feel distressed, it can exude a toxic goo that will blister your skin. If ingested, the goo could be fatal. The beetle is dangerous if crushed. There have been instances when horses died because they ingested hay that was contaminated with crushed beetles.

The beetle pictured at the top of the page comes from India. Here (below) is a less colorful cousin of that beetle. This one lives in the U.S.

Black Blister Beetle(Epicauta pennsylvanica)

Credit:Bruce Marlin.CC 2.5 attribution Share alike license

The blister beetle belongs to the family Meloidae; there are approximately 3000 species of beetle in this family. They may be found in most parts of the world, but not in New Zealand and Antarctica.

The blister beetle is phytophagous, i. e., it feeds on green plants. As such, it is considered a pest. I've read through gardening sites where people were desperate for a way to rid themselves of the insect. The problem is complicated by the fact that they are toxic when they are dead. The bodies have to be handled with care or an animal might come in contact with them.

The Minnesota Cooperative Extension, for example, cautions farmers about purchasing hay.

Buying alfalfa hay from out of state increases the risk of getting hay infested with blister beetles. While rare, blister beetle-infested hay can cause health problems and death in horses and other livestock. If you find black, elongated beetles in your hay, dispose of it.

Here is a YouTube video of the bug up close. Oil beetle is an alternate name given to this insect. That is because of the toxic oil excreted from its joints.

As I read about the life history of this bug, it became apparent to me that the insect's path through life seems to generally be at the expense of other creatures.

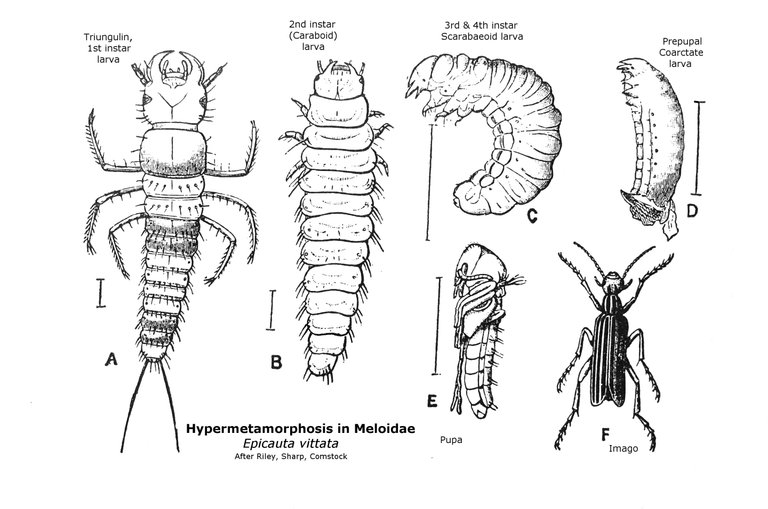

The blister beetle goes through a complex metamorphosis as it develops. One of its stages is parasitic on wild bees. Blister beetles go through hypermetamorphosis--several stages of development.

Blister Beetle Stages of Development

Credit: Comstock, in "Introduction to Entomology", 1920. 1920. Public

The female beetle may lay her eggs in a number of places: in the soil, on stems, on leaves or on flowers. The first larval instar (stage of development) is the triungulin--as shown above. This is a mobile stage. Sometimes, at this stage the larvae will climb up a stem and wait for a suitable host. In the YouTube video shown below, the host is used for transportation, not consumption.

The larvae climbed up the stem of a plant and released a chemical that mimics a female bee's pheromone. The duped male bee attempts to mate with the larvae horde. They attach themselves to the hapless lover. He goes off to mate with an actual female bee. The larvae transfer to her body and she carries them, unawares, to her nest.

In the nest, the beetle larvae consume foodstuffs intended for the bee's young, and they also consume the young. The larvae soon metamorphose into the next instar, a grub-like stage, and continue eating. Eventually the beetle larvae metamophose into two more stages before going into the pre-pupal carapace (called pseudopupal stage), and then into the pupal stage. They may spend up to two years as pseudopupae.

Blister Beetle With Orange Poison Drop on Its Thorax

Darkone (talk contribs). CC 2.5 generic license

Different blister beetle species have different egg-laying strategies. Some lay their eggs around grasshopper eggs. The grasshoppers, instead of bees, become nutrition for the larvae. Some farmers may welcome the beetle as a grasshopper control, but this can be a poor trade-off because the beetles are so injurious to crops and dangerous to farm animals.

The Poison

The poison I have referred to throughout this blog is Cantharidin. The concentration of cantharidin varies by beetle species. In some species the poison may compromise as much as 5% of the beetle's body weight. Females tend to carry five times more of the poison than males.

The poison is used defensively, not offensively. The beetle may excrete cantharidin from only one leg, if that leg is pulled. It may excrete the poison from its neck, or all of its legs if it feels distressed. Its ability to excrete this toxic substance has the effect of protecting it from predators. Most spiders will not eat blister beetles, although a species of orb-weaver spider, Argiope florida, ate it readily in one study.

Credit: Bob Peterson from North Palm Beach, Florida, Planet Earth! CC 2.0 generic

It's interesting that in this study, those spiders that rejected the beetle didn't simply refuse to eat. They actually cut the beetle loose from the web and even severed strands of web that had made contact with the beetle.

Another animal that eagerly consumes blister beetles is the Great Bustard.

Credit:Andrej Chudý from Slovakia: CC 2.0 Generic license The male Bustard eats a great quantity of blister beetles during mating season especially. It seems the beetle is effective at clearing out a parasite that inhabits the bird's digestive system. This makes the male more attractive to the female (according to the website Ornithology: the Science of Birds)

As an extension of its defensive properties, a cantharidin-laced substance is smeared over her eggs by the female blister beetle.

Cantharidine Effect on Humans

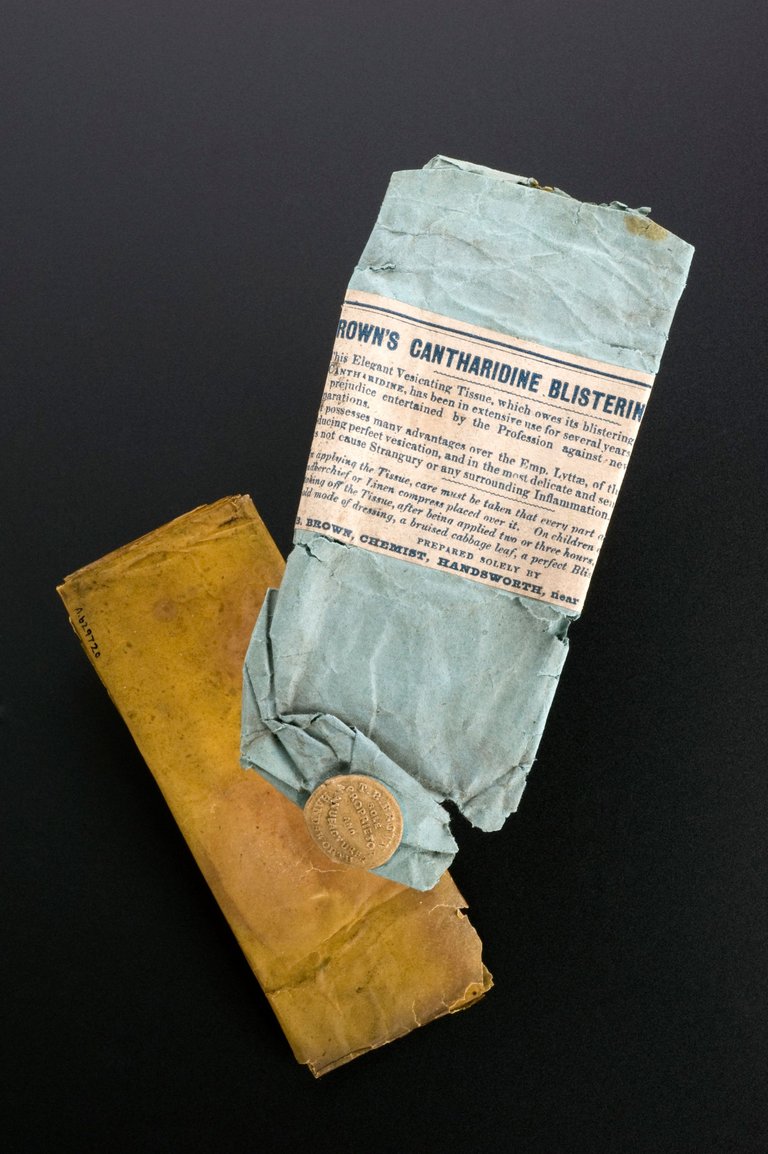

Cantharidine has a long history with humans. It has been used as an aphrodisiac, a poison, and as a treatment for a variety of medical conditions. In the picture below, there is featured 'Cantharine Blistering Tissue". This was a medical treatment that was once recommended to treat inflammation.

This file comes from Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom. Refer to Wellcome blog post (archive). Used under CC 4.0 attribution-share Alike international license. The caption under this picture reads in part: "It was used as a counter-irritant, the technique being to irritate one part of the body, raising blisters on the skin, in order to relieve it in another. Care had to be taken when applying the cantharidine tissue, as it could cause excessive damage if not used cautiously. It was recommended that a handkerchief or piece of linen be placed over it when used on adults – a cabbage leaf was recommended for children."

One notion about cantharadin that has persisted for centuries is that this substance can be used as an aphrodisiac. The image below shows the beetle that is presumed to be the source of so-called 'Spanish Fly'.

Partly because of the perception of cantharadin as an aphrodisiac, partly because of ignorance, and partly because of malice, humans have been poisoned systemically by this substance. There is a case reported for example, of a soldier who accepted a bet to eat a beetle. Six hours later, that soldier was very ill. He was treated at a hospital for "abdominal pain, dysuria, gross haematuria with clots, hypotension, fever and renal insufficiency." He was treated with intravenous fluids and in a week his stats had returned to normal.

Lytta-vesicatoria, Beetle With Vulgar Moniker 'Spanish Fly'

Credit Franco cristophe. Used under CC 3.0 Attribution share alike license

A paper I discovered from 1954 discusses several cases of systemic cantharadin poisoning, some deliberate. The paper was co-authored by an MD at a Scottish hospital and the Director of the Scotland Yard police laboratory. In a one case, 25 people were killed when some Slovakian men laced chocolate with a related compound. They were hoping to see the chocolate act as an aphrodisiac. They rented a room so they could watch the orgy they thought would ensue.

There is one approved medical use (Approved by FDA in 2023). It can be applied as a topical preparation to treat a viral, contagious, skin condition, molluscum contagiosum.

Conclusion

There is so much to say about this fascinating beetle. The most important thing, though, is to emphasize its danger. There are ways to kill it--soapy water is recommended, for example--but in killing it, one should wear gloves, and not cloth gloves. Be aware that the beetle plays dead when shaken from a plant. It may appear to be dead but just be pretending. Also, even dead, the beetle is toxic.

Thank you for reading my blog. Hope it was interesting and readable. Hive on!

Selected Sources Used to Write the Blog

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/cantharidin

https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/urban/medical/blister_beetles.htm

http://extension.cropsciences.illinois.edu/fieldcrops/insects/blister_beetles/

https://www.gardeningknowhow.com/plant-problems/pests/insects/blister-beetle-control.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blister_beetle

https://ornithology.com/blister-beetles-and-bustards/

https://bugoftheweek.com/blog/2017/10/6/look-but-do-not-touch-blister-beetles-iepicauta-pensylvanicai-and-ie-funebrisi

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/cantharidin

https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/0-306-48380-7_541

https://uwm.edu/field-station/bug-of-the-week/blister-beetle/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/phytophagous-insects

https://extension.umn.edu/horse-nutrition/blister-beetles-alfalfa-hay

https://www.britannica.com/science/hypermetamorphosis

https://www.poison.org/articles/blister-beetles-do-not-touch-194

https://www.ricecountymn.gov/DocumentCenter/View/7645/Blister-beetles-are-booming-this-year

https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co178206/cantharidine-blistering-tissue-in-original-wrapper-england-1855-1875-plaster

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4432444/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2080332/pdf/brmedj03628-0026.pdf

https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a623044.html

https://www.planetnatural.com/pest-problem-solver/garden-pests/blister-beetle-control/