Hi buddies,

I'll open by saying that understanding how biology rules our world will play a leading role in how we fight and treat diseases that have plagued us all along. There's no arguing the fact that, our immune system performs an excellent job of keeping us alive by fighting off external invaders such as germs and viruses. However, it's your own body that is an invader in the form of cancer cells, which are experts at evading the immune system.

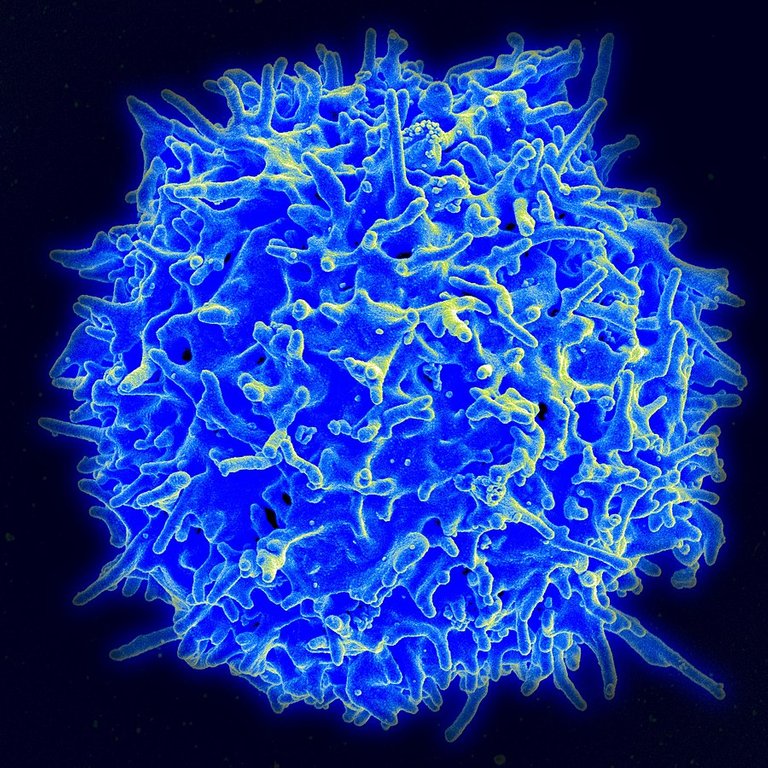

According to a recent study published in the journal Nature, it may be possible to train the immune system outside the body to maintain leukemia patients in remission for up to a decade. T-cells are one of the many types of cells that make up our immune system. Each T-cell specializes in recognizing and/or attacking a certain type of invader.

Scanning electron micrograph of a human T lymphocyte (also called a T cell) from the immune system of a healthy donor ; Source ; Public Domain

T-cells are covered in unique proteins called receptors (i.e., proteins on the surface of invaders like bacteria and viruses) that are designed to hook up with antigens in order to perform their job effectively. T-cell receptors, in other words, are more like chemical keys on the lookout for their lock. However, some illnesses, such as cancer, are masters at eluding t-cell keys. They can do this by not having enough detectable antigens on their cell surfaces, for example.

The good news is that scientists have discovered a way to extract t-cells from a patient's body, train them to detect cancer cell antigens, and then reintroduce them into the patient to fight cancer. This is known as (CAR)-T-cell therapy or CHIMERIC ANTIGEN RECEPTOR therapy. T-cell training is a sort of genetic engineering that involves a lengthy and complicated procedure. A piece of DNA is finally inserted into the T cells' genetic code, instructing them to create a specific receptor for the cancer cell antigen.

The procedure of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR) is depicted in the figure above.

- T-cells (objects with the letter 't') are extracted from the patient's blood.

- The gene that codes for the specific antigen receptors is then inserted into T-cells in a lab setting.

- The CAR receptors (labeled as c) are then produced on the cell surface.

- The newly changed T-cells are extracted and cultured in the lab after that.

- After a certain time period, the engineered T-cells are infused back into the patient

Source ; License

As a result, when the freshly customized receptor latches onto its target, the t-cell calls for backup by releasing a slew of cytokines. The cytokine molecules and the army of t-cells work together to generate inflammation, which kills their targets in the best-case scenario.

While (CAR)-T-cell treatment has been approved for a few forms of cancer, little study has been done on the long-term implications. The duration of a single T-cell infusion in the body and whether the patient remains in remission are two examples of such effects. However, in 2010, two patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia were given a single dose of CAR-T cells, and the therapy was so effective that both patients went into remission within a year. The incredible part is that they've remained that way without any extra therapy. The most recent blood work was taken a few years ago, and the team discovered that both patients still had some CAR-T cells in their blood streams.

While these are excellent findings, they do not imply that every leukemia patient will be enrolled in the program. When it first began, there were 14 patients in the cohort, however only two (2) were included in the 10-year follow-up. Furthermore, this medication is known to cause a variety of unpleasant side effects, including difficulty breathing and even seizures.

Still, further research is needed to improve CAR-T cell side effects, making it a viable choice for cancer prevention. A study published in the journal Science Advances has shown that it is feasible to assist African clawed frogs recover the upper part of their amputated limb. We humans may be able to stitch cuts together or even rebuild a significant portion of our liver, but we are not famed for our regeneration abilities. Unlike lizards and crabs, who can regrow intricate body parts such as entire limbs, we are unable to do so.

African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) ; SourceLicense

The way it works in these animals is that their brains identify that a portion of their body has been lost, and unspecialized cells called stem cells rush to the stump and begin working. As a result, they progress from unspecialized cells to bone cells, muscle cells, nerve cells, and other types of cells. Because their bodies have already gone through the process of creating that limb, the instructions are to create a new one. We have STEM cells, too, but instead of sending STEM cells when we lose a limb, our bodies send signals to cover it with scar tissue as fast as possible so we don't bleed out or get an infection.

The researchers wanted to see if they could use 115 female African clawed frogs to trigger limb growth in humans. These animals don't have regeneration ability as adults, so if they lose a leg, it's gone for life. To test their idea, scientists chopped off a portion of one rear limb and either left the frogs to heal on their own as a control group, or covered their wounds with a small silicone cap packed with silk proteins and a 5-drug cocktail.

Each drug had a specific purpose: to reduce inflammation and the creation of scar tissue, as well as to promote normal tissue growth. The scientists had only used one medicine in a previous study, and while it did grow something back, it was more of a spike than a leg. As a result, it appeared as though there was a flash growth with the first stage of bone regrowth visible.

However, in this latest study, the caps were worn for 24 hours before the researchers observed what grew over the next year and a half. Just a few days in, the team observed that for the frogs that got the drugs, the molecular instructions their bodies had used as embryos had reactivated. And over the course of those 18 months, they grew back into the shape of a leg. While none of them resembled the frogs' other leg, two-thirds of the frogs who were administered the medications had regrown much more sophisticated tissues and leg structure. They were even able to regrow toes, but not toe bones, according to researchers. The frogs' legs could also respond to touch and be used for swimming. All of this in only one treatment day!

To conclude the blog, this research is focused on amphibians, and human trials are still a long way off. A lot more work is needed to figure out what the perfect drug cocktail needs to be to regrow the best limb possible. The prospects are promising, I envision a world where people may be able to select whether they wish to recover a missing limb or have the benefits of a robotic one decades from now. It's not impossible!

You can share your thoughts below as well! Cheers y'all

And perhaps you're interested in checking out more details, Check these links:

Decade-long leukaemia remissions with persistence of CD4+ CAR T cells

TCell

Scientists regrow frog’s lost leg

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell

Acute multidrug delivery via a wearable bioreactor facilitates long-term limb regeneration and functional recovery in adult Xenopus laevis

Posted from HypeTurf