Today I invite you to take a small tour of the Želiv Monastery, located about 120 km southeast of Prague, the capital of the Czech Republic in Central Europe.

I must confess two sins at the outset. My English is so bad that I use Deepl.com to translate. And secondly, the photographs are only an illustrative accompaniment to my reasoning.

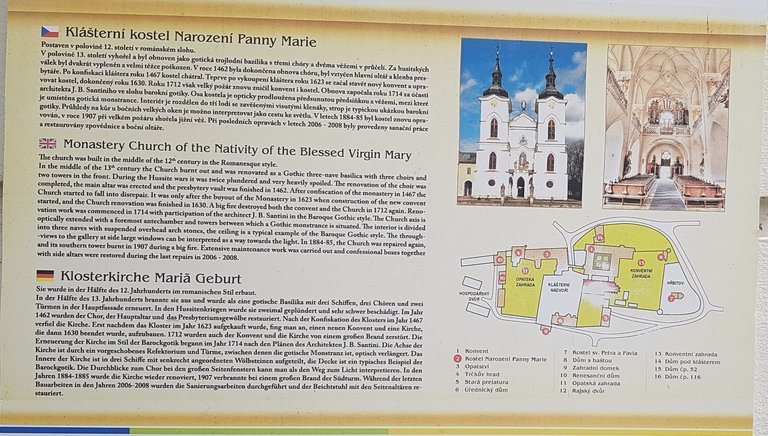

We are in a huge monastery complex, which hides the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary as a pearl inside. The first photo shows a small part of the interior, the second a frontal view of the church, the third an information sign where you can read something about the church if you are interested.

Everywhere you look there are cars parked, unfortunately. The complex is alive. There's a Premonstratensian monastery, some buildings have been converted into apartments, a hotel, a restaurant and a brewery. There are pilgrims and tourists everywhere. ... But couldn't the cars be parked somewhere else?

I'll start right away with these considerations. Is history repeating itself? No, they don't. But some events do repeat. For example, World War I, World War II. Here in Bohemia, we number defenestrations, i.e. throwing someone out of a window for national and political reasons.

Czech children are taught in schools about the 1st Prague Defenestration, which started the Hussite Wars in the 15th century, and the 2nd Prague Defenestration, which started the Thirty Years' War in the 17th century. Actually, there were more defenestrations in between, but for the sake of simplicity Czech children are not taught about them.

What does this have to do with the Želiv Monastery? It was a victim of religious wars and for two centuries it was mostly abandoned and decayed.

Cars wherever you look!

Czech children also learn about the period of so-called normalisation. In 1948, the communists came to power in our country and established a government of lawlessness and terror, as they are already able to do. In the 1960s, it seemed that better times were on the horizon. The consequences of the worst communist crimes began to be condemned. They began to talk about socialism with a human face.

In the church there is a memorial to a priest who was beaten during interrogation by the communist secret police in the 1950s. He wasn't the only one, but his case received a lot of publicity.

On August 21, 1968, Soviet and allied tanks invaded us. Once again, a regime of lies, pretence, stagnation and violence was established in our country. The communists called it normalization.

It was while visiting this monastery that the word "normalization" came to mind. It was not the first time in our history in 1968.

In the 16th century great religious freedom reigned in the Czech lands. About 20% of the population were Catholics, the rest adhered to various Protestant religions. The rulers were Catholic, but they were forced to respect the status quo.

In 1618-1621, the Bohemian lands rebelled against the monarch. And the leaders of the uprising ended up on the scaffold. (About a quarter of a century later, the English Parliament rebelled against its monarch, and the monarch ended up on the scaffold. The difference was that we didn't have Oliver Cromwell then.)

The triumphant monarch in our country proceeded to normalisation. A new constitution was issued. The monarch became an absolute monarch. All religions except Catholic were banned and the first borders with heretics flared up. This is how it will last in our country for the next 160 years. Just normalization.

Even absolutely negative things sometimes have some positive effects. The structure of Catholic parish churches needed to be restored. Churches were baroquized. And there were some really brilliant architects. The Želiv monastery is the work of J.B. Santini-Eichel. A new school of architecture called Baroque Gothic style was born. The buildings and reconstructions of that time are really beautiful.

Disenfranchised peasants in the countryside languished. But music, architecture, art and painting flourished. Works of art were preserved.

In the church, the orchestra was beginning to rehearse for the evening classical music concert. I sat and listened. What's that in the photo? This is supposed to be a holy water jar.

The church is also a miraculous place of pilgrimage. The faithful throw their prayers into the former baptismal font. God sees into our hearts and is good. Why shouldn't wishes come true?

I wrote that the monastery also includes a restaurant and a famous microbrewery. I was visiting the church with friends. My friends went for a beer. I listened to baroque music.

I want to come back here for sure. Then I'll try the local beer.

For today, the Želiv Monastery bids you farewell.

I also bid farewell with an attempt at a black and white photograph.

And it's really over.

První česká normalizace

Dnes vás zvu na malou prohlídku Želivského kláštera, který se nachází asi 120 km jihovýchodně od Prahy, hlavního města České republiky ve střední Evropě.

Hned na začátku se musím přiznat hned ke dvěma hříchům. Moje angličtina je tak špatná, že k překladu používám Deepl.com. A za druhé, fotografie jsou pouze ilustrativním doprovodem mých úvah.

Nacházíme se v obrovském klášterním komplexu, který jako perlu uvnitř skrývá kostel Narození Panny Marie. Na první fotografii je malá část interiéru, na druhé čelní pohled na kostel, na třetí informační cedule, kde si v případě zájmu můžete o kostele něco přečíst.

Všude, kam se podíváte, jsou bohužel zaparkovaná auta. Komplex žije. Je tu premonstrátský klášter, některé budovy byly přestavěny na byty, hotel, restaurace a pivovar. Všude jsou poutníci a turisté. ... Ale nemohla by ta auta parkovat někde jinde?

Začnu hned s těmi úvahami. Opakují se dějiny? Ne. Ale opakují se některé události. Například I.světová válka, II.světová válka. My tady v Čechách číslujeme defenestrace, tedy vyhazování někoho z okna z ná boženských a politických důvodů.

České děti se ve školách učí o 1.pražské defenestraci, která zahájila období náboženských, husitských, válek v 15. století a o 2.pražské defenestraci, která v 17.století zahájila Třicetiletou válku. Ve skutečnosti těch defenestrací bylo v mezidobí víc, ale kvůli zjednodušení se o nich české děti neučí.

Jak to souvisí s Želivským klášterem? Nepřímo. Stal se obětí náboženských válek a dvě století byl většinou opuštěný a chátral.

České děti se také učí o období tak zvané normalizace. V roce 1948 se u nás dostali k moci komunisté a nastolili vládu bezpráví a teroru, jak to už oni umějí. V 60.letech se zdálo, že se blýská na lepší časy. Následky nejhorších komunistických zločinů začaly být odsuzovány. Začalo se mluvit o socialismu s lidskou tváří.

V kostele se nachází památník kněze, který byl v 50. letech 20. století ubit při výslechu komunistickou tajnou policií. Nebyl jediný, ale jeho případu se dostalo velké publicity.

- srpna 1968 k nám vtrhly sovětské a spojenecké tanky. V naší zemi byl opět nastolen režim lží, přetvářky, stagnace a násilí. Komunisté tomu říkali normalizace.

Právě při prohlídce tohoto kláštera mě napadlo slovo „normalizace“. Ono to v roce 1968 nebylo v našich dějinách poprvé.

V 16.století zavládla v Českých zemích obrovská náboženská svoboda. Asi 20% obyvatelstva byli katolíci, zbylí se hlásili k různým protestanstským náboženstvím. Panovníci byli katolíci, ale byli donuceni respektovat stávající stav.

V letech 1618-1621 české země povstaly proti panovníkovi. A představitelé povstání skončili na popravišti. (Asi čtvrt století na to rebeloval anglický Parlament proti svému panovníkovi a panovník skončil na popravišti. Rozdíl byl v tom, že my jsem tehdy neměli Olivera Cromwella.)

Vítězný panovník u nás přikročil k normalizaci. Byla vydána nová ústava. Panovník se stal absolutním monarchou. Všechna náboženství kromě katolického byla zakázána a vzplanuly první hranice s kacíři. Tak to u nás bude trvat dalších 160 let. Prostě normalizace.

I naprosto negativní věci mají někdy pozitivní účinky. Bylo třeba obnovit strukturu katolických farních kostelů. Kostely byly barokizovány. A existovali opravdu geniální architekti. Želivský klášter, jeho obnova, je dílem J. B. Santiniho-Eichela. Zrodila se nová architektonická škola zvaná gotické baroko. Stavby a přestavby z té doby jsou opravdu nádherné.

Bezprávní rolníci na venkově živořili. Zato hudba, architektura, umění a malířství vzkvétaly. Umělecká díla se zachovala.

V kostele začínal orchestr zkoušet na večerní koncert vážné hudby. Seděl jsem a poslouchal. Co je to na té fotce? To má být nádoba na svěcenou vodu.

Kostel je také zázračným poutním místem. Věřící vhazují své modlitby do bývalé křtitelnice. Bůh vidí do našich srdcí a je dobrý. Proč by se přání neměla plnit?

Napsal jsem, že součástí kláštera je také restaurace a vyhlášený minipivovar. Kostel jsem navštívil s přáteli. Kamarádi šli na pivo. Já poslouchal barokní hudbu. Chci se sem ještě někdy určitě vrátit. Pak snad ochutnám i to pivo...

Pro dnešek se s vámi Želivský klášter loučí. Loučím se i já pokusem o černobílou fotografii. A to je vážně konec.