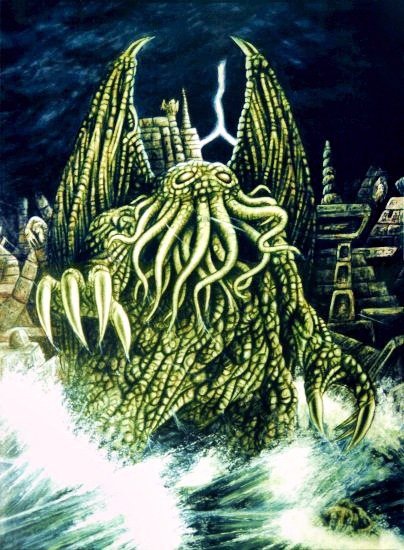

From the pantheon of Lovecraftian cosmic horror Cthulhu is the character which has seeped, like an insidious ichor, into the collective conscious of popular culture. Without having read any of H.P. Lovecraft’s output many will recognise images of a large, green, tentacle faced creature from numerous representations in memes, cartoons, and even crocheted animals. It is strange that this secondary deity from the pantheon is more remembered than its progenitor, Yog-Sothoth. Yog is an omniscient being, dwells outside what we perceive as the universe so is unbound by time or space and, apart from Cthulhu, fathered two semi-human children.

It is possible Cthulhu’s popularity is due to a sympathetic resonance between the constant subconscious anxiety Cthulhu is portrayed as engendering in the human race and ongoing feelings of dread, terror, and vague unease which swirl like an unwholesome miasma around the fringes of modern life and whose tendrils reach further and further from the edge towards the heart of what is mockingly called normality.

The Call of Cthulhu, the first story in which the titular character appears, was published in nineteen-twenty-eight in a magazine called Weird Tales. Founded in nineteen-twenty-two, the pulp magazine with brightly colored, attention grabbing, frontpages ran until nineteen-fifty-four, although ownership changed a few times during those years. Since then, there have been various attempts to resurrect the title. Apart from Lovecraft that original run of the magazine saw stories by the Likes of Robert E Howard, Robert Bloch, and Ray Bradbury.

Writing stories for pulp magazines was not a way to become rich. While a favoured writer may reach the dizzying heights of a full American cent per word, lesser-known submitters may find themselves offered a rate of half, or quarter, a cent. Submitting to magazines then, as today, is a process which requires an ability to deal with copious rejections. H P Lovecraft never enjoyed such an ability and would abandon projects to lie unloved after a single submission to a preferred magazine. This is a feeling many a writer will be able to empathise with. Stories of people who had a story or manuscript rejected dozens of times before a marquee acceptance are passed round with glee, but no-one talks about writing a story for a specific call, it not being accepted for inclusion, and then it being abandoned to lie unlooked at amongst story fragments, rough drafts, and loosely gathered research notes.

Today, more than ever, it can feel an impossible task, as a new writer, to have your work published in magazines. In days of yore, you needed to physically type out your story, package it, post, it, and wait. Many people just didn’t have the time, nor inclination.

Now, the ubiquity of devices to write upon means being tied to a typewriter at a desk is not a thing. One well-known trilogy started as fanfiction being written on a phone during the writer’s commute. It is almost impossible to find a café where someone is not hunched over their laptop or tablet, pecking away at the keyboard, in pursuit of their magnum opus.

However, while there are a plethora of venues to submit work to for publication, they are literally swamped by the number of submissions received. Having been a first reader on three different magazines I have seen the sheer volume of work available, and the level is not diminished if the venue pays lower, semi-pro, rates of pay. Even venues that pay a nominal amount, or are publication only, receive more submissions than they can reasonably use. The people who volunteer as First Readers at these venues are to be greatly admired, especially where they manage to do it for years on end. I burnt out inside a year for each of the times I did it, though learnt from each of them.

One of those things learnt was how magazine editors spend more time worrying about the expense of running a magazine than nearly any other aspect of the process: There is a limited amount of space for stories, so they develop a keen eye for stories which fit the required style; publication dates are set, so they know when layouts need to be completed by; they don’t need to worry about submissions, they flood in. But they do need to worry about funding: About whether the parent publisher is considering shutting the magazine or lowering pay-rates; or editors are looking at the Patreon, Kickstarter, or like, and wondering if there will sufficient take-up to remain in business.

Most writers don’t write for the money, they write for the love of writing, or their characters. That’s not to say writers don’t want remuneration commensurate with their efforts but, and especially writers of short stories, know they are going to need more income streams than professional rate paying magazines can supply them.

Still, the editors of these magazines are conscious of what James D. Macdonald called ‘Yog’s Law’. In simple terms it is that money should flow to the author, and not from them, in relation to their work being published.

James was writing about the dangers of vanity publishers when he coined the term. A vanity publisher offers to take your manuscript and turn it into a book, but they ask you, the author, to pay the costs. This is not self-publishing, where a writer knowingly undertakes the process of producing and selling their work, but rather an underhand way for unscrupulous people to play on the wishes of would-be authors.

And these people prey on a Cthulhu-like madness which many an unpublished writer succumbs to, the desire to see their name in print.

You may think, with the relative ease of self-publishing today, that such scams would be in decline. The website Writers Beware – sponsored by the Science Fiction Writers of America - suggests differently. They keep a database of people and companies who prey on unsuspecting writers, helpfully showing the links between some who have been scamming for years. They also look at contests with practices which damage the writers who submit to them, such as ones who decided to publish submitted stories on their website without having any contract with the writer.

A new entrant into the field of fleecing writers of their money while pretending to be assisting them in their dream of publication is A.I.

While there is no such thing as true artificial intelligence the rise of Large Language Models is being bent towards publishing. These use a set of algorithms to statistically analyse an inputted manuscript against data it has been trained on.

A new venture which has captured seed money from investors offers to take five-thousand dollars from a writer, use an LLM to ‘proof-read’ the manuscript and publish it with ‘artwork’. There’s even an offer of ‘translation’ services.

As a business model, ‘give us five-k and we won’t read your manuscript before slapping a cover on and pushing it out’ is a particularly egregious violation of Yog’s Law. It is a Cthulhu Call, a clarion cry to madness, a trap designed to lure the unwary, the ingenue, the plain old gullible.

While NaNoWriMo has somewhat tarnished its brand many folks still use November as an opportunity to push ahead with a planned novel. By the end anyone who has made a social media post suggesting they are writing is likely to be bombarded with adverts and even direct messages offering publication packages or representation for their work. Whether the novel is completed or not will be irrelevant.

Those reading these ads and messages must remember to ignore Cthulhu’s Call. Yog’s Law says money flows to the writer, not away from them, and Yog is older and more powerful than Cthulhu, no matter how much old tentacle face tries to tickle your brain with fears of remaining unpublished.

text by stuartcturnbull, art by Dominique Signoret