Hello friends. I find it hard to believe that so many visitors to Sunny beach, Bulgaria remain unaware of a massive, secret underground tunnel a mere 6 kilometers away. This incomplete underground tunnel was planned as part of the Odessa-Burgas railway. Construction of this railway began after World War II and was intended for the rapid transport of military equipment in the event of an attack. In 1946 an order was issued to draft a project for such a railway. During the same period, a dry dock for submarines was also built in the Varna region.

Today I want to share our visit to this hidden structure located just 6 km from Sunny beach. This site is not only an example of unique mid-20th-century engineering but also holds a fascinating history.

To get here you first need to arrive at Sunny beach. Our walking route started in the village of Kosharitsa, about 4 km from Sunny beach. We reached Kosharitsa by car, but you can also get there by bus or bike. To reach the first southern portal of the tunnel, you’ll need to walk roughly 2 km along a dirt road. At the very beginning of the path, you’ll see the first concrete bridge pillars of the never-completed railway. Along the way you’ll encounter remnants of infrastructure prepared for the railway but never put to use.

While walking we came across numerous concrete structures. Most were built for water diversion and to ensure the stability of the railway infrastructure. Let me also share a bit about the history of this tunnel, which bears the marks of the past.

The Odessa-Burgas railway was planned to facilitate the swift movement of troops and heavy equipment in the event of an attack. Construction began in 1951 but by the late 1950s, the development of nuclear weapons and missiles rendered the project unnecessary and it was completely abandoned. Even today many concrete structures and infrastructure elements built during the project remain visible.

When we reached the tunnel’s southern portal, we were struck by the sheer size of the structure. Everything was built on a massive scale and is quite impressive. Despite being incomplete, this site stands as a remarkable historical relic, waiting for visitors to explore its story.

The Odessa-Burgas railway was planned as a single-track line. An interesting detail is the difference in rail gauge widths: 1524 mm in the Soviet Union versus 1350 mm in Romania and Bulgaria. When construction was abandoned, 800 meters had been excavated on the southern side of the tunnel, while 450 meters had been dug on the northern side. Inside the tunnel there’s an actual flowing river with fish swimming in it. However, the ground is very slippery, making it challenging to proceed without proper equipment.

The tunnel is 6.5 meters high and some electrical poles are still in place. However, venturing too far inside is not possible. If you plan to visit, you’ll definitely need specialized footwear, ideally rubber boots. Sneakers are absolutely unsuitable for this journey. While the water inside isn’t tempting enough for a swim, there are fish swimming in it and who knows. You might even encounter a mutant fish. 😄

On the sides of the main tunnel, there are two smaller portals and what appears to be a staircase leading upward. However, determining where these stairs lead or how to ascend or descend them is challenging. The area is dotted with numerous concrete structures, whose purposes remain unclear. Some seem to have been constructed to reinforce the mountain, while even mundane concrete cube-like structures have been swallowed by nature over time.

Like every tunnel, this one also has an entrance and an exit. To reach the northern portal, you need to cross the Balkan Mountains (Stara Planina). However, this route is not marked on any maps. Google Maps, Maps.me or other navigation apps don’t show it. While trying to find the right path, you occasionally encounter trails, but there’s no certainty about where they lead.

On our way to the northern portal, we found what looked like an old path. As we continued, the slope became steeper. After about 2.5 kilometers of walking, we arrived at a mountain pass. Here, there was a clearing with what seemed to be a hunting ground. As we pressed on, the forest trails started intersecting, leaving us uncertain about which direction to take.

When we got as close as possible to the northern portal, we encountered a fence. This fence appeared to be part of a large hunting area and stretched for about 500 meters in either direction. Passing this point to reach the northern portal was nearly impossible. Circumventing the fence would mean a 15-kilometer detour, so we decided to take a direct route via the village of Prisece.

From Prisece village the hike to the northern portal is roughly 5 kilometers. You can drive an off-road vehicle closer to the portal. However, we faced a river crossing upon arrival. The weather was quite cold and the water was icy.

In summer crossing the river might be a pleasant activity, but at this time of year, the shallow pools were coated with a thin layer of ice. Thankfully, my boots kept me warm. About 1.5 kilometers from the village, we reached a fork in the path. Using a power line pole as our reference point, we turned right. The road was muddy and filled with puddles, making progress challenging. I would recommend making this trip during a dry season.

Along the path, we noticed various animal tracks, particularly hoof prints. A sign in the forest read, Enter at Your Own Risk which made us feel a little uneasy. We joked about hoping not to encounter any wild boars. About 1.5 kilometers from the northern portal, we saw our first moss-covered concrete structure, likely part of the railway’s infrastructure. The trail followed a small stream and eventually led us to a concrete wall, likely built to prevent erosion from the stream. These massive concrete structures reflect the permanence sought during that era. Today, such a problem would probably be solved with wire mesh, but back then, everything was built to last for centuries.

The trail wound up the mountain and we arrived at a spot with two massive concrete pillars. These were likely intended for a railway bridge that was never completed. After crossing the bridge remnants, we encountered another stream. This time, we managed to cross without getting our feet wet. About 500 meters from the tunnel entrance, we found a trail overrun by weeds but still visibly well-trodden. We noticed numerous wild boar tracks, but the path itself seemed frequently used.

When we reached the tunnel entrance, we saw that the northern portal was simpler than the southern one. The entrance was partially sealed with stones, leaving only a narrow passage. Interestingly, this tunnel was once used for growing champion mushrooms. While the southern portal is more ornate and impressive, the northern portal’s height of 8 meters is notable.

Entering the tunnel, we were greeted by high humidity and echoes. The walls featured technological niches, old insulators and small stalactites in some places. The tunnel stretches about 2 kilometers, ascending slightly. Certain sections were dry and suitable for walking, while others were muddy and waterlogged.

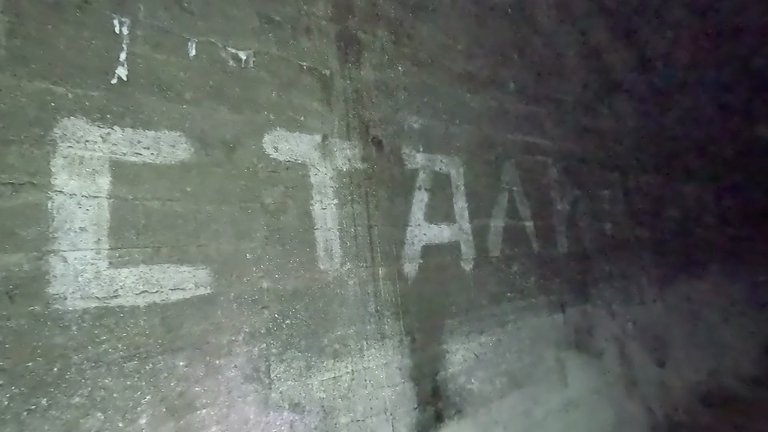

Inside the tunnel, we saw traces of old slogans on the walls. One inscription, Greetings to Stalin caught our attention. Whether it dates back to the 1950s or was added later remains a mystery. Exiting the tunnel it took some time for our eyes to adjust to the daylight again. Near the exit we saw crumbled and damaged concrete structures, likely buildings for tunnel guards or railway personnel.

On our way back, we had to cross the stream again. While this stream might be great for cooling off in the summer, wading through icy water in January was less enjoyable.

At the end of our journey, we crossed an unfinished viaduct, a half-completed bridge standing as a monument to the ambitious dreams of the past. These structures remain as enduring reminders of a time when projects were built to withstand the test of time.