She had been climbing since morning, as she did every day before the dark moon rose. The way was well worn, and she let her memory guide her upwards to the small cave that looked out on a narrow ledge and then to infinity and the pale white sky. She had been making this journey every year since the ships left, remembering the grandmothers and searching the night sky for the red planet and the sky she remembered from childhood. It was a place of memory and loss, necessary and constant in a world of uncertainty. A yearly ritual to remember what came before her.

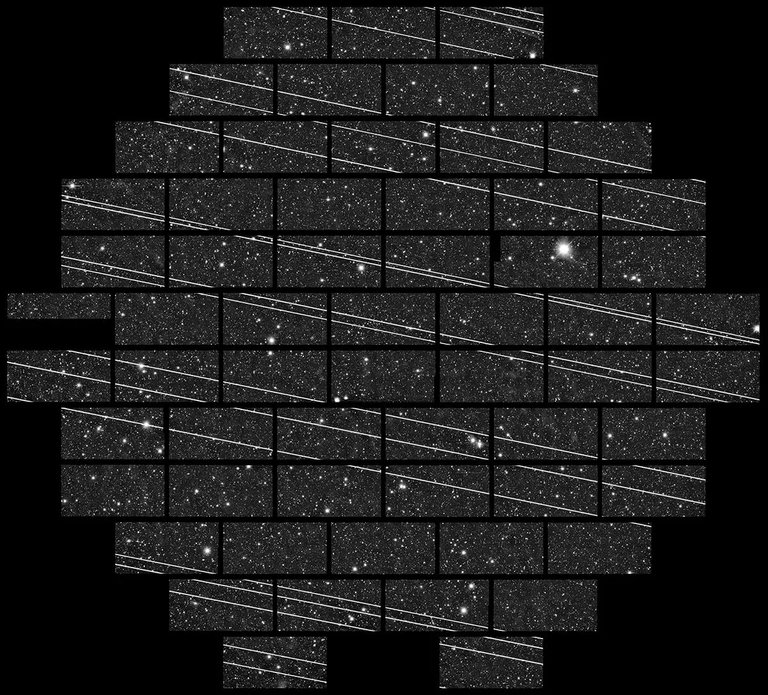

In the first decade of her lonely climbing, the satellite streaks were still tearing the fabric of the black quilt that had hugged the earth for millenia. The stars were not as brilliant as when she was a child and used to climb the mountain with her gran. But this year she had met a man who said the satellites were blinking out this year. Intending to swap a jar of sugar syrup for three homemade arrows, he stayed for months. He told her many stories, and the sound of another human voice made her happy for a time. He said that he used to work for Starlink. Said the satellites were programed to blink out if no one reset them, as if someone waa anticipating the end of the world and wanted the return of the night skies of old.

Starlink trails

She thought of tens of thousands of space debris colliding in the vastness of space. Sometimes they were pulled by earth's gravity, landing into the sea, the forests, the buildings. There were not many people around to witness. The ones who had stayed died of the worst pandemic to hit mankind since COVID-19, and the rest were hurtling to Mars and beyond, looking for other places to die. She remembered those days and took a deep gulp of the humid, wet air as if to compensate. Her whole teenage years were spent in masks and isolation, and even now, many years later, she woke at night and could not breath and tore at her face, attempting to remove the ghost of a mask that she had crippled her so. She could not imagine being in space, knowing that one was dependent on technology for oxygen.

When her mother applied for the position of being the first woman to go on Elon Musk's space flight to Mars in '27, a year later than planned, her grandmother and her brimmed with pride. Her mother was young, brilliant and vivacious, and despite having a child early, was accepted onto the flight after three woman before her pulled out. The youngest had died after contracting the virus, one had disappeared in mysterious circumstances involving another astronaut, and one simply decided it was no longer for her, retreating to a forest monastery in Tibet to watch the dying planet gasp from there. The Starlink man held her hand and said he remembered her mother. Said she was brave. But was it not braver to stay, she argued?

Pulling herself up onto the ledge, she took a moment to let her lungs settle and release their painful grip on her heart. It was a mixture of physical exertion as well as grief. This day was not easy to live, but live it she must, as all those left on Earth must. Even the Starlink man who gave her sugar syrup, with his sad eyes and stories of why he'd chosen to stay behind, sighed often with regret and loss. He stayed for the winter. They shared a bed and she told him stories of her grandmothers and all the wise things that they had told her in her dreams. He told her they were not real, but she could feel them in her cells. An ancestral memory. In the Spring he was gone. He needed to pace out his own story and it was not threaded to hers but to the other he was searching for. She did not mourn a man who had no memory of his grandmothers, or chose not to listen to them.

In 2027, the year her mother left for Mars, she began to release what it meant to be alone. Her grandmother took her last breaths on the sky ledge where they had climbed to watch the last sunset of the year. She would tell her stories of the land, of her ancestors. Tales of strong woman who knew the earth like a lover. Told her how they made the world with their bare hands. Of grandfathers their were none to speak of. When she asked, her grandmother would be silent for a while, and tell her how to make a bow and arrow or how to skin a rabbit or how to make a soothing ointment from flowers and beeswax.

Her grandmother was fit and strong, but that was no protection against the cancer that had not told her daughter about. 'It's remarkable', she said, 'that it was your mother that was chosen. Imagine. The first woman on Mars'. She left her grandmother on the ledge as she was not strong enough to carry her down. In the winter, the ice turned her flesh to crystal, which shattered when the wind blew her down to the valley. She liked to think of her grandmother becoming one with the sky and land scavengers that would have torn at her defrosting flesh in the Spring. One with the Earth. Could you be one with Mars? She thought of all her grandmothers, stretching far back in time. Not one of them had a relationship with the Red Planet. Not one. Their goddesses were here, on this dusty and tired planet that one had to fight for breath upon.

In 2028, her mother chose not to return. 'I could see the fires as I left' came the message through time. Twenty minutes to hurtle through space to her. 'It's Earth that is becoming the red planet'. She thought of those years of wild fires and the impossibility of breath. Masks this time filtered not just viruses but the toxicity of cities burning, millions of hectares of forests. She was utterly alone then. It was easier that way. She hunted and trapped and plucked wild herbs from the mountains like her great, great grandmothers. She thought of their skin sunburnt like hers, their feet calloused like goats from rocky mountain scampering, lighting fires in rock huts to cook rats and birds.. Snow rabbits, often, and the occasional trout. Did her mother think of her ancestors on Mars as she tended the soils of the biomes? Could she breath up there? Did the air smell like it did here, crisp in the mountains in winter or tainted with fires in the summer?

Between '28 and '42, most of the population of Earth had left, either this mortal coil entirely or on what they called the First Fleet. There was not other Fleet, because there was no one around to build the ships or to send them hurtling through the stars. Sometimes people would call it the Last Fleet, or in grim memory, the Doomed Fleet. Eventually the messages did not come, because the means to recieve them disintegrated by fire or flood or the fierce shaking of the Earth. But she had stopped listening. Why should she listen to a mother that had severed the umbilical cord that linked herself to her child and all her mothers, including the great mother of them all, the Earth that bore them and bore witness to their destruction?

Her breath returning now, she entered the cave with her satchel of paints, made from the rocks in the valley below. The mural was nearly finished. Here were the grandmothers, in the forests and the mountains, holding herbs, picking mushrooms, planting and hunting. Here was her mother, cradling her as a baby, holding her hand as a toddler, pointing at the stars. Here was the launch of the satellites, the great plague, the fires. Here was her grandmother on the sky ledge, telling her stories. Here was her with the Skylink man, and him leaving her with belly round.

As it got dark she put down her paints and stepped out onto the sky ledge. For a moment she did not think it was the same Earth, but he was right: the satellites had at last given up their vigil of the earth, the constant beaming of signal to those no longer around to listen or to care. On the horizon the red planet rose, and the stars, sharp and vivid against the night sky.

Next year she would bring her daughter here, and tell her stories of the grandmothers. She would point to the red planet, and remember her mother, the first woman on Mars.

This was a response to the Ladies of HIVE topic for this week, which asks whether, as a woman of Hive, I'd accept an opportunity to go on the first mission to Mars in 2026. Somehow it became a work of fiction rather than fact, but I hope it conveyed my answer well enough. It as fun to write on this hot, hot day in summer, thinking about the end of the world as we know it, and what might come after. Please forgive errors of continuity - it's a rough draft only and needs much editing, when I have the time! The collage is my own.

With Love,

Are you on HIVE yet? Earn for writing! Referral link for FREE account here