Has this festive season caught you toe-tapping to Carol of the Bells; humming along to White Christmas; or pulling a private, questionably sexy rendition of Santa Baby? Whether with nonchalant disdain or jolly vigour, this season has most of us moving to a well-known beat. From shopping districts to private homes, we catch the notes of rich hits – it’s a period where even the hardiest non-conformist finds himself or herself twitching to a well-rehearsed verse.

Christmastime in Cambridge

Christmastime in Cambridge

This break, I have found myself back at the piano. And it has me thinking… whether I’m pressing keys or listening to a Spotify playlist with bated anticipation, I find myself drifting out of the present moment and into something more surreal. Music is transportive, but why? The powerful words “Give me hope, Jo’anna” takes one back to the 80s in midst of the anti-apartheid movement. “Flower of Scotland” puts a lump in the throat of any Scot; oh, to stand against Proud Edward’s Army for wee bit hill and glen. And how does the sound of that lone trumpet at the Anzac Day Dawn Service make you feel?

Sound is a crucial part of our everyday lives – just think about it. We use it to enhance our moods, for entertainment, and for better immersion and/or emotional attachment. Even the ambient tones of an elevator tune have presence… but music is just so abstract - why are we drawn to it? From an evolutionary perspective, it doesn’t make sense that certain chord progressions spark different emotions.

Inspired by this train of thought, I’ve been listening to several podcasts on the subject – episodes from New Scientist and Hidden Brain come highly recommended. According to Zatorre, music can stimulate feelings of euphoria and craving, similar to tangible rewards that involve the striatal dopaminergic system. But why? Dopamine is released when we have good sex. It is released when we eat. Yet, music isn’t biologically essential to our survival in the same way that love-making or consuming food is... we don’t need it to survive. Turning up the volume and head banging to Bohemian Rhapsody won’t increase out lifespan.

However, the paper by Zatorre and his team suggests that music actually activates the same reward system that boosts dopamine hits one derives from sex and food, despite its lack of biological necessity for survival. One potential explanation lies in our innate affinity for patterns, a trait likely honed through evolution for survival purposes. The ability to discern patterns may have been crucial in determining threats, such as interpreting if rustling in the trees signalled an imminent danger from a wild animal or if the scent of smoke warranted swift action to escape a potential fire.

Dinner in the Hague, Netherlands

Dinner in the Hague, Netherlands

This morning my partner surprised me with breakfast in bed. While we ate delicious omelettes in cosy covers, he played from his phone the John Moorland episode from Tiny Desk Concert. Moorland might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but I found his lyrics, supported by beautiful melodies, soothingly melancholic. It was a perfect morning – inspiring another hypothesis for why, when we hear a piece of good music, we latch onto its rhythm. Music is a form of language and, naturally, humans engage in communication, whether it's through spoken words, expressive tones, or subtle sighs. This, I believe, can be attributed to a process called “entrainment”.

Ethnomusicologist Joseph Jordania, proposes that the capacity of humans to be entrained evolved through natural selection, playing a crucial role in attaining a distinct altered state of consciousness known as “battle trance”. Moreover, sound in general functions as a signalling system, doesn’t it? It alerts and warns us in various situations. Consider the familiar ring of a cell phone notifying us of calls and messages or the distinct horn of a train cautioning those nearby of its presence. Cars honk as a means to warn or even startle others. In essence, sound acts as a bridge in our communication infrastructure, facilitating phone conversations and providing essential alerts that contribute to the seamless flow of our daily lives.

Doesn’t it intrigue you that humans may be the only species on Earth capable of knowing when to start and stop drumming their fingers to a beat (bar aunty Kate)? Most of us communicate verbally, as it’s pretty hard to understand body language alone. If music can tell us about character, place and time by creating memorable, immersive experiences, it does so by form of speech.

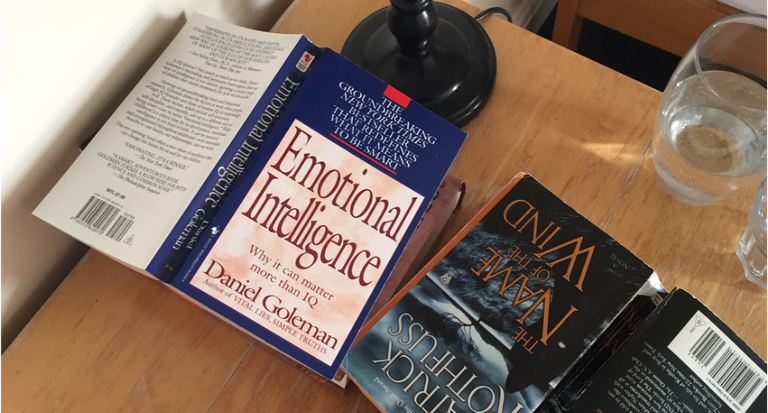

Which brings me to my final point. Has anyone here heard of “emotional contagion”? Mirroring feeling plays an essential role in our subsistence. I believe I first came across this term in Daniel Goleman’s book, Emotional Intelligence. Emotions are shared across individuals in many ways, both implicitly or explicitly. I think this is perhaps another reason for our love of music. Yes, it plays a crucial role in our survival, serving as a constant informant about the environment, spatial awareness, objects, and ongoing actions.

Snapshot of the bedside table

Snapshot of the bedside table

There’s no denying that, if you are human, you're ensnared by music. It is an integral part of our daily existence. Sounds, in essence, are vibrations – whether you’re tapping away at the white keys of a piano or dancing to the thump of a drum in a nightclub. Those who are hard-of-hearing or deaf can still “listen” to music, just not in the way hearing people experience this process. But I should stop now - if interested, this last point is more fully addressed in the Sound of Life Blog.

Sound, by definition, is inherent in us all, isn't it?