Black Garden Ants on Philippine Leaves Image credit: Judgefloro. Used under CC 1.0, Public domain license.

In a recent blog for the LMAC community I explained how I was obliged to deal with an ant issue in my home. In that blog I featured the picture of an ant I had captured. The ant was slowly expiring. This death drama is one I watched many times after an exterminator came to my home.

Before he came, I had to dispatch the ants myself, with quick and unflinching force. In the face of all the sudden, and slow, death, I wondered if ants suffered. It seemed to me, as they died, that they were in pain. I'm aware that their responses to threat and death might be dismissed as simple, primitive reflexes. Many researchers hold this point of view.

An article I found on the website of the Entomological Society of Canada suggests, in fact, that insects cannot feel pain. According to Dr. Shelley Adamo of Dalhousie University, insects cannot feel pain, as we understand it. He states, "The lack of output neurons in insects limits the ability of the insect brain to sew together the traits that create pain in us."

@agmoore. An ant I captured on a paper towel

And yet, despite Dr. Adamo's assertion, a search on Google Scholar yields research that suggests otherwise. There is a plethora of research articles that posit, with different degrees of probability, that ants, and other insects, do feel pain.

One 2023 article from PLOSBiology asks, "Is it time for insect researchers to consider their subjects' welfare?" The authors of the article go over research that looked for clues in insect "nervous systems and behavior". In their analysis of the research, the authors reviewed 300 studies that considered six different insect groups. They used eight criteria established by the UK government for detecting pain in nonverbal subjects (subjects that cannot verbalize their experience of pain).

@agmoore. The ant in distress. It was given a quick death after this shot

Some of the pain assessment criteria looked at the insect nervous system to ascertain whether the basic physiological equipment exists to allow for the experience of pain. The following nervous system elements are considered essential to an insect's feeling pain: (From PLOSBiology)

- 1 Nociceptors (receptors that are sensitive to stimuli).

- 2 Brain regions that that can integrate sensory input.

- 3 Connection between the nociceptors and the brain regions that integrate information.

The PLOSBiology authors (cited above) explain that insects do have nociceptors that respond to a variety of stimuli, and the niciceptors connect to 'higher order' brain regions. In the brain regions information from the nociceptors is integrated with other sensory input. These facts seem to satisfy the basic physiological requirement for feeling pain.

What other clues exist to build the case that insects feel pain?

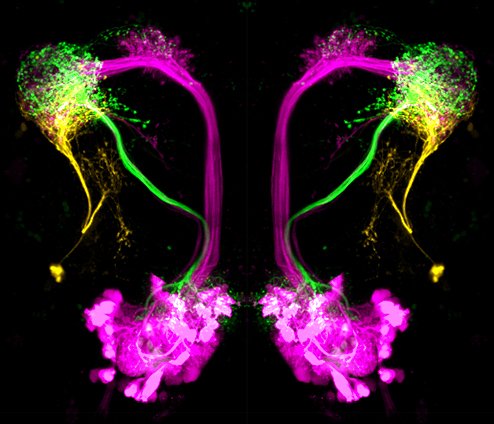

Neurons in Drosophila (Fruit Fly) Brain

Credit: e-life the Journal. Used under CC 2.0.

The Drosophila may be the most studied insect in science laboratories. Experiments with the Drosophila go back more than 100 years (Thomas Hunt Morgan, January, 1910). To the untrained eye, the picture above this paragraph seems to show a Drosophila brain with highly integrated neurons. What does research indicate?

Drosophila melanogaster Image credit: Andre Karwath aka AKA. Used under CC 2.5 license.

A 2021 article published in the journal eLife reports that there is "functional connectivity" between neurons in the Drosophila brain, and that these neuronal signals are "integrated". This seems to satisfy the three physiological requirements for feeling pain.

I looked at another insect, the dragonfly--not related to the fruit fly. Fruit flies are in the order Diptera. Dragonflies are in the order Odonata, but the dragonfly has an interesting brain when it comes to neuronal connectivity.

If you watch this YouTube video and skip to 11.16 minutes in, you will see that the brain of the dragonfly receives and integrates information.

According to this video, the dragonfly's brain uses a 'strategy' that allows it to predict behavior of its prey. This predictive predator strategy requires more brain processes than simply tracking prey.

Behavior

In addition to the basic physiological basis for feeling pain, there are behavioral clues researchers look for to indicate that insects feel pain. The clues described below are derived from PLOSBiology.

- 1 Do painkillers work? That is, when an insect is administered an analgesic, does this alter the response to 'noxious' stimuli?

- 2 Does the insect show the inclination, or ability, to choose between noxious stimuli and potential reward? Does the insect actually weigh (called a trade-off) the reward vs. the risk? Here the scientists look for "flexibility" in the trade-off that would indicate there is some kind of "integrative processing" of information.

- 3 Does the insect show "self-protective" behavior. This would be, for example, tending a wound. Or rubbing and grooming a wound.

- 4 Learning. Does the insect seem to learn from being exposed to noxious stimuli and does this learning lead to avoidance of that noxious element?

- 5 Does the insect show an interest in analgesics? This would involve actually self-administering the analgesic, or a preference for the location where an analgesic might be found. This interest in pain relief (analgesics) might even be demonstrated when the insect chooses an analgesic over another "need", such as food.

An article from Smore Science addresses an insect's ability to learn and to avoid pain. The authors cite an experiment where a fruit fly's leg is wounded, deliberately. After the leg heals, the fruit fly's other legs become hypersensitive. The fruit fly demonstrates avoidance behavior: "After the animal is hurt once badly, they are hypersensitive and try to protect themselves for the rest of their lives,” the authors explain.

Cockroaches Feel Pain?

One surprising piece of information I picked up in my reading about insect pain is that cockroaches rate high in the scale of pain sensitivity.

Madagascar Hissing Cockroach Image credit: Husond at English Wikipedia. Used under CC 3.0 license.

A 2022 article in the journal Advances in Insect Physiology explains how different insects rate on the UK pain scale described earlier in this blog. Using that UK list of criteria, these authors found that strong evidence exists for pain in (adult insects) two orders: "Diptera (flies and mosquitoes) and Blattodea (cockroaches and termites). The authors also found substantial evidence of pain in " Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, ants, and sawflies), Orthoptera (crickets and grasshoppers), and Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths). Insects in this group satisfied 3-4 of the UK criteria.

Why Do We Care?

I care. I've killed a lot of ants over the past month. Although many times I was angry with them for invading my home, I always felt regret that this worthy enemy had to be killed. In killing the ants, I didn't want to inflict any more suffering than was necessary to reclaim my home. The question arose: were they suffering, or was I anthropomorphizing these arthropods?

There is a larger concern when considering the possibility (probability) of insect pain. Increasingly, the research community is acknowledging standards for treatment of animals used in experiments. Is it ethically imperative that we extend this protection to insects? I can imagine the uproar in the research community at such a ruling.

A quote from the Advances in Insect Physiology Journal states the issue clearly:

From an ethical standpoint, whether insects feel pain is an urgent question. There are currently no guidelines for considering their welfare...and they are almost universally excluded from animal welfare legislation.

The insects are excluded because traditionally it was believed they do not feel pain.

But what if they do?

Conclusion

I recognize that many of my readers will dismiss this subject out of hand. It complicates life to think about insects feeling pain. So much research that advances human medicine is based on insect research. Will that research be impeded by worrying about insect welfare? I don't have any answers, but I think we should all understand the choices we make. Learning more about insect pain will advance that understanding.

Thank you for reading my blog.

https://esc-sec.ca/2019/09/02/do-insects-feel-pain/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10234516/

https://www.qmul.ac.uk/media/news/2022/se/insects-may-feel-pain-says-growing-evidence--heres-what-this-means-for-animal-welfare-laws.html#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20framework%2C%20this,crickets%2C%20and%20grasshoppers%20fulfil%20three

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1369702111701134

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8616581/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/diptera

https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/misc/odonata/odonata.htm

https://www.smorescience.com/do-ants-feel-pain/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0065280622000170

https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/117533/

https://www.understandinganimalresearch.org.uk/what-is-animal-research/a-z-animals/fruit-fly#:~:text=The%20first%20documented%20use%20of,work%20with%20the%20fruit%20fly.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10441753/

https://www.smorescience.com/do-ants-have-brains/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2010.00028/full

https://academic.oup.com/icb/article/53/5/787/733390

https://isctj.com/index.php/isctj/article/view/257