Last week I came across a curious bit of information: There exists an apparent correlation between a bat fungal disease and infant mortality. The correlation has been observed in many areas of North America, where bats are perishing in large numbers from white nose syndrome.

An Obviously Annoyed Little Brown Bat With Symptoms of White Nose Syndrome

University of Illinois/Steven Taylor. US. Fish and Wildlife Used under CC 2.0

White nose syndrome, WNS, is endemic to Europe and Asia. The syndrome wasn't found in North America until 2006, when the fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, was introduced. As a novel pathogen, the fungus had the ability to devastate an immunologically naive bat population. And it did.

In China and Europe, this fungus disease seems to have little impact on the bat population. In North American affected areas, bat populations have declined by as much as 90% (in some cases 100%) of affected communities.

The fungus may be essentially wiping out the bat population in some parts of the U.S., but what does this have to do with human babies?

Bats are an important part of the ecosystem. They're insectivores--they eat insects. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a small bat can eat 1,000 insects in an hour. A mother bat, nursing her young, can eat 4,000 in an hour. Bats can be one of a farmer's best friends.

Leaf Hopper Nymph (Cicadellidae)

Credit: Katja Schulz from Washington, D. C., USA. Used under CC 2.0 license. According to the USDA, bats are one of the most important consumers of night flying insects. Their diet includes mosquitoes, moths, beetles, crickets and leafhoppers (such as the one shown in the picture above).

What happens when there are no more bats? What does a farmer do to control insect pests? Apply pesticides. The deleterious effect of environmental pesticides on maternal health and perinatal health has long been established.

Researchers were recently startled to find this relationship between bat decline and infant mortality, and that relationship, they posited, was established by the use of pesticides.

Farmer Spraying Pesticide on a Field

Credit:Photo by Jeff Vanuga, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. Public domain. A 2008 report issued by Farm Worker Justice.org describes the ways in which occupational exposure to pesticide influences fertility/childbirth. The article describes how the pesticide interferes with male fertility. How it affects female fertility, gestational health, breast milk.

After reading about the WNS/infant mortality connection, I was curious: Was this the first time agricultural use of pesticides correlated clearly with infant health/mortality?My answer popped up quickly in a Google search.

There was a study out of Sudan in 1993 which looked at exactly this relationship. In an article entitled "Agricultural Pesticide Exposure and Perinatal Mortality in Central Sudan", the result of studies that looked at the risk of pesticide exposure was clear:

Exposure to any pesticide spraying significantly increased the risk of stillbirth in the hospital population and of perinatal death in the community population

and

Pesticide spraying most significantly affected perinatal deaths in women engaged in farming

Then there was an article published by the Journal for Gestational Education (2008), which did an overview of literature that studied environmental exposure to pesticides and herbicides. The authors of this overview state:

Suggestive evidence associates pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls with decreased fetal growth and length of gestation.

and

Evidence suggests dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane and bisphenol-A could be associated with pregnancy loss

It's not hard to find studies that draw a relationship between insecticide exposure and a number of fetal abnormalities. What's interesting is that some of this exposure is through ingestion, rather than through air.

Here's another study (2021), for example, from the International Journal of Environmental Research, that looks at the effect of pesticide exposure in a variety of countries. The results are similar to those described in the two studies already cited.

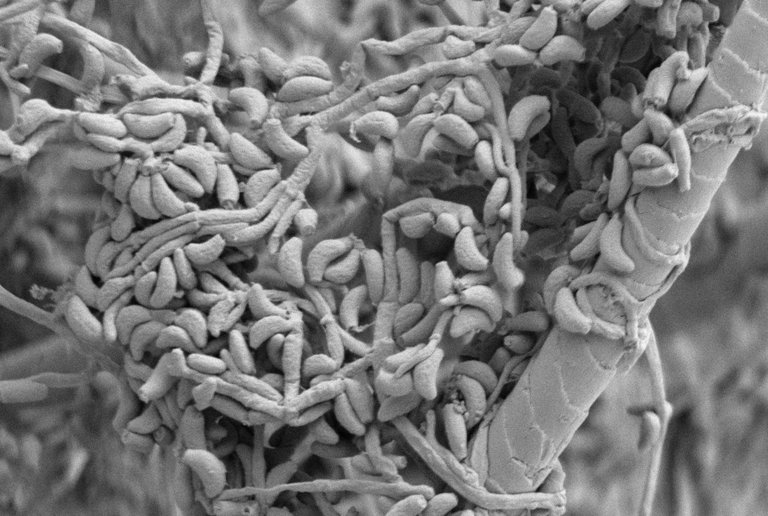

Geomyces Destructans Infecting a Bat

Credit:Djspring. Used under CC 3.0 Attribution Share-alike license.

White Nose Syndrome

As researchers look at this fungal disease their understanding of its etiology grows. Pseudogymnoascus destructans is psychrophilic--it is adapted to a low-temperature environment. The implication of this for bat illness is that when a bat is hibernating, its body temperature is reduced. The bat hibernates because of the scarcity of food (insects) during winter. The cold-loving fungus thrives in this reduced body temperature environment. This is also a time at which a bat is most vulnerable.

Hibernating Bat

Brent and Marilynn. Used under CC 2.0. The picture seems to have been taken in Nashville, TN.

Although the fungus disease is called white nose syndrome, the fungus attacks more than the bat's nose. The fungus can grow on the wings, nose and ears of an affected bat. When the bat comes out of hibernation, the white fuzziness may go away, but the fungus invades deep tissue. Not only does the fungus weaken the bat directly, but when the bat is hibernating the fungus causes it to have more frequent periods of arousal.

Bats ordinarily are aroused periodically during hibernation. Those periods of arousal are costly, in terms of energy and resources (stored fat) used. The fungus therefore weakens the bat systemically and also by causing exhaustion of fat reserves.

Tri-colored Bat With Visible WNS Symptoms: Wings, Ears and Nose

Credit: Darwin Brock. US Fish and Wildlife. Used under CC 2.0 license

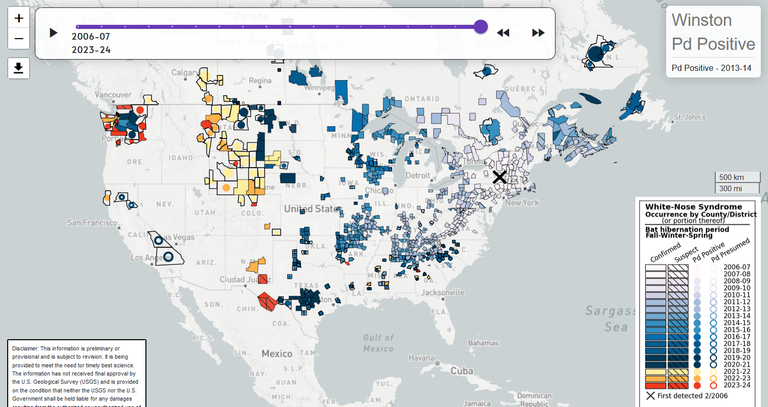

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife, white nose syndrome has spread rapidly, and continues to spread. It is in 40 U. S. states, and in Canada. There are teams of researchers and interested individuals who are working to combat the disease. It is believed the fungus must have been introduced by a human who visited a cave in Europe. It could have been carried in on a shoe, or boot.

However, (as mentioned previously) bats in Europe seem to have built up immunity to the syndrome. According to an article in BMC Zoology, " We hypothesised that WNS exerted historical selective pressure in Palearctic bats, resulting in genomic changes that promote infection tolerance." Palaeactic refers to Old World regions; Nearctic refers to New World regions.

Below is a relatively current distribution map of white nose syndrome's spread in Nearctic regions. If you click on the link, you will find yourself at an interactive map that shows the rapid spread of the disease since 2006.

Credit: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Public domain.

White nose syndrome has not infected humans. This fungus likes cold temperatures. Human bodies are simply too warm for it to thrive.

Conclusion

When I write a blog I first of all look for a subject that interests me. The association between white nose syndrome and infant mortality I found fascinating. Also, when I write, I like my blog to have some significance. In this case, we see once again how different parts of nature cannot be walled off. Everything is connected. The association between bat disease and human infants is a pretty dramatic illustration of that connection.

Thank you for reading my blog. Hive on!

Some Resources Used in Writing This Blog

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/immunologically_naive

https://www.britannica.com/science/Holarctic-region

https://www.usda.gov/peoples-garden/pollinators/bats

https://www.msn.com/en-us/health/medical/how-a-bat-disease-may-have-led-to-the-death-of-more-than-1-000-kids/ar-AA1q4bmn?ocid=winp1taskbar&cvid=d0ec4ec2cf484a11acd6379ea70a00ef&ei=41

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8324850/

sudan report on infant mortality and pesticide use

https://voxdev.org/topic/health/herbicides-widely-used-agriculture-increase-infant-mortality

Brazilian agriculture and pesticide use correlation with infant mortality

https://www.nps.gov/articles/what-is-white-nose-syndrome.htm

https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/bat_crisis_white-nose_syndrome/Q_and_A.html

https://www.bats.org.uk/about-bats/threats-to-bats/white-nose-syndrome/white-nose-syndrome-in-europe

https://news.ucsc.edu/2015/11/bat-disease-china.html

https://www.nature.com/articles/srep19829

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fseprd476773.pdf

https://www.americanfarmlandowner.com/post/helping-the-bats

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4833532/

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adg0344

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1933719108322436

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8471259/

https://bmczool.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40850-018-0035-4

https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/93/2/497/922002

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adq5157

https://wdfw.wa.gov/species-habitats/diseases/bat-white-nose#wns

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306456521002758

https://bmczool.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40850-018-0035-4

https://www.britannica.com/science/Holarctic-region