QUIENES FUERON MIS PADRES

Estaba recogiendo los becerros, como hacía todos los días, cuando el sol de los venados estaba en su apogeo. Tarareaba gritado un ritmo de esos que entonan los llaneros en tiempo de trabajo de llano. Yo con mis siete u ocho años me desempeñaba muy bien y me divertía mucho corriendo detrás de los becerros. El potrero no era muy grande. Yo creo que no llegaba a dos hectáreas. Como era el potrero más pequeño, le decíamos el potrerito. En las mañanas, después de ordeñar las vacas, mi padre me decía:

-Hijo, arree los becerros al potrerito.

Otras veces:

-Amarre mi caballo de silla que está en el potrerito. También: -Encierre en el corral las bestias que están en el potrerito

-¡Corre! ¡Corre!. ¡Corre!. ¡Corre!, muchacho que te alcanza la vaca!

-¡La vaca! ¡La vaca! La vaca! Gritaba otro

Alertado por los gritos miro hacia atrás y me doy cuenta que una vaca recién parida venía con toda su furia hacia mí. Sin pensarlo dos veces, salí corriendo para evitar que me alcanzara. Ya iba a llegar a la cerca del potrero, miro de reojo que la vaca todavía me sigue. En los últimos 10 metros aumenté la velocidad y de un brinco, digno de competencias olímpicas, pasé por encima del alambrado de la cerca sin tocarlo, con la misma velocidad que caí me levanté y corrí hacia el corral, como la puerta del tranquero estaba cerrada, me lancé y pasé a través dos trancas. Todavía no me había levantado del piso cuando oí el ruido que propició la vaca al chocar violentamente contra las trancas del tranquero. Me quedé paralizado por unos segundos y luego corrí a mejor resguardo.

Hay vacas que cuando están recién paridas son muy celosas y si uno pasa cerca de donde está el becerro le embisten. Yo en otras oportunidades había vivido esta experiencia, pero no tan comprometida como en esta ocasión. Las personas que estaban observando la escena, empezaron a reírse y hacer chistes que a mi no me agradaban. Mi madre dijo:

-Yo le pedía a la virgen que la vaca no fuera a cornear a mi muchacho.

Otro se preguntó:

-No me explico cómo Baudilio pasó por entre las dos trancas. Creo que ni las tocó. ¿Te golpeaste? me preguntó.

-No, no sentí ningún golpe. Ni cuando salté el alambre de la cerca. Me acuerdo que caí di vuelta y quedé parado por eso la vaca no me alcanzó en ese trayecto.

-Cuando corrí hacia el tranquero vi una luz que había entre dos trancas y por ahí me lancé.

Ya mas tranquilo, observé la altura del alambrado y sentí una emoción interna por haber saltado una altura mayor a un metro; inmediatamente también sentí escalofríos al imaginarme lo peor si la vaca me hubiera alcanzado. Dije en silencio: menos mal que el tranquero estaba cerrado. Luego agradecí a Dios por estar sano y salvo.

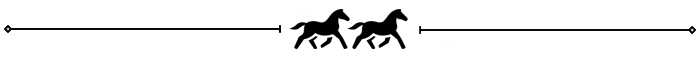

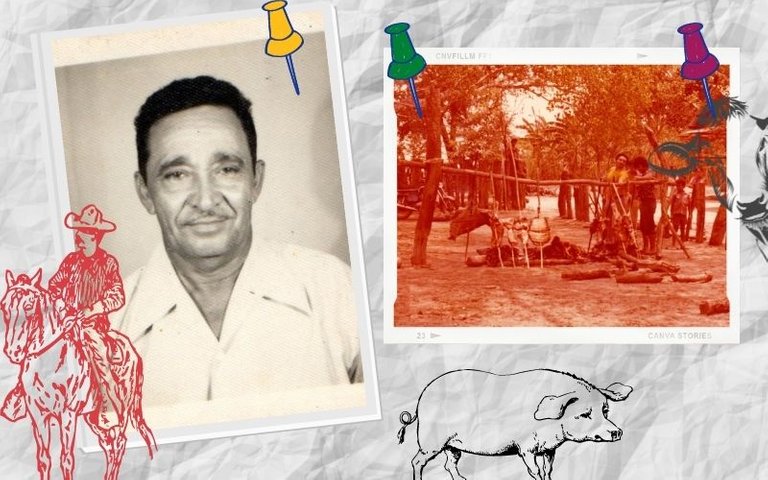

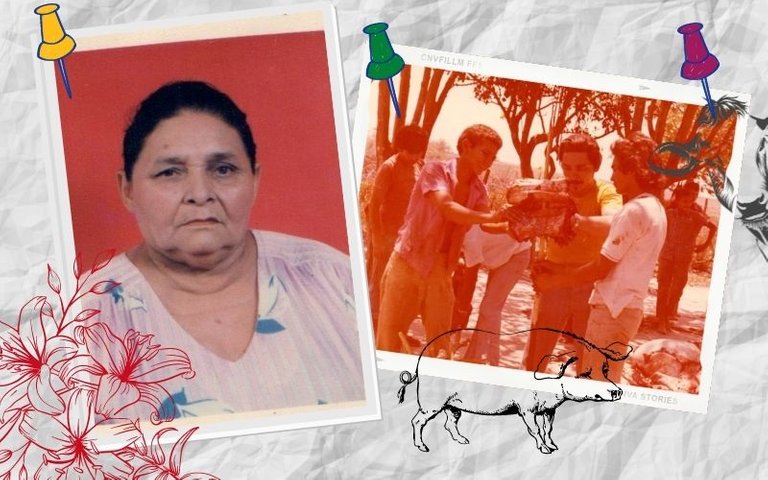

LA IDENTIFICACIÓN

Mi madre no salía del asombro. Ella era una mujer blanca, linda, un poquito más alta que mi padre. En ese momento observé sus ojos llorosos, unas lágrimas hicieron acto de presencia en sus ojos verdes. Se me acercó y me abrazó. Me dió un abrazo protector que todavía lo recuerdo. Cuando se inclinó para abrazarme, sentí que su pelo largo y negro acariciaba mi cabeza y mi rostro. Yo también le di un abrazo de hijo agradecido.

Mi padre estaba un poco más retirado hablando con dos señores. Se reía y a la vez alababa la forma como salí victorioso de la situación peligrosa. Y agregó:

-Hijo, así es como uno se va haciendo hombre en el llano. Para hacerse un llanero completo tiene que vivir y experimentar muchas situaciones de peligro.

Los señores que hablaban con mi padre, compartían y aprobaban lo dicho por él con movimientos afirmativos de cabeza. Uno dijo: -Es verdad.

A mi madre no le gustó mucho el comentario de mi padre. Confieso que a mí tampoco. Esperaba un apoyo como el que me dió mi madre. Contó, en ese momento, que él a mi edad, había, vivido muchas situaciones peligrosas. Escuché que agregó:

-Yo a la edad y tamaño de Baudilio me persiguió un toro que me dió un cabezazo y me lanzó como a cinco metros. Me paré y seguí corriendo todo golpeado, sin llorar porque delante de mi abuela Petra era prohibido que un hombre llorara.

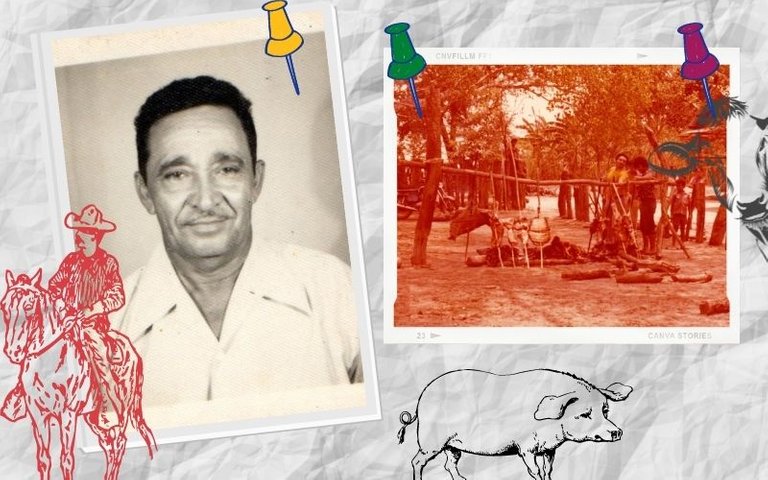

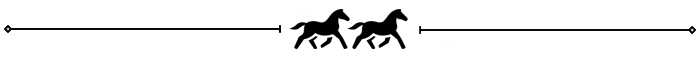

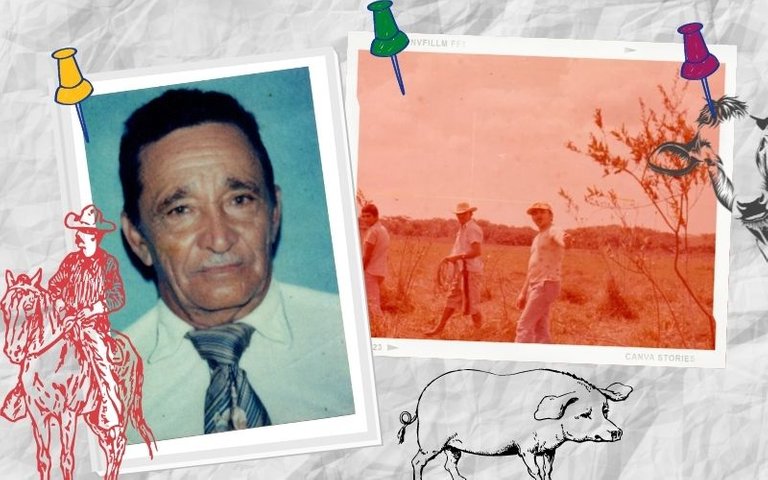

Mi padre era un hombre moreno de mediana estatura. Siempre alegre, bien parecido. Le caía muy bien a la gente y en especial a las damas. Era lo que en el llano se llama un hombre de a caballo porque se desempeñaba muy bien en los trabajos de llano. El había aprendido, bajo la tutela de su abuela Petra, todo lo que un hombre debe saber del llano.

Mi padre contaba que cuando iba a trabajar llano a los hatos hacía pareja con un amigo, hermano o familiar para enlazar a los mejores toros mañosos, decía que se divertía luciéndose en ese sentido. Sabía enlazar muy bien. Cuando estaban en el corral para herrar y marcar becerros, era el primero que empezaba a enlazar. Toreaba o coleaba si había necesidad de hacerlo. Yo lo vi muchas veces en el fundo toreando animales que le embestían. Lo hacía con la soga con el sombrero o con la camisa. En una oportunidad que no cargaba el sombrero ni la soga y sin tiempo para quitarse la camisa, con un movimiento habilidoso eludió el toro que lo embistió, luego lo agarró por el rabo y al colearlo lo tumbó. Yo aplaudía la hazaña y me sentía orgulloso de mi padre.

-Rondón, meta esa vaca en otro potrero. Ahí es un peligro para cuando vayan a recoger los becerros.

Ordenó mi madre pero con voz amorosa. Ella era así. Cuando tenía discusiones con mi padre nunca actuaba de manera violenta. A veces parecía débil, pero no lo era. Cuando había que actuar lo hacía. En una oportunidad cuando vivíamos en el pueblo un muchacho del barrio me atacó, nos fajamos a pelear en eso llego mi madre con un mandador y yo creí que venía a liberarme de la pelea. Me amenazo con castigarme sino peleaba para que dejaran de molestarme. La madre del muchacho quiso intervenir y mi madre le dijo:

-No se meta usted y si quiere nos agarramos las dos. Invitación que ella no aceptó. En ese momento no era la Rubina que yo conocía.

Mi hermano José Mercelino, su nombre era Marcelino pero la escribiente le cambió la “a” por “e”, así quedó, me contó que estando en una central telefónica en San Carlos, estado Cojedes, una señora llegó a molestar a mi hermana María Anastasia nombre que le puso mi padre en honor a su madre. Mi hermana le decía que no molestara que estaba en una llamada importante para ella. La señora insistía. Mi madre se da cuenta y se levanta de la silla y hala a la señora por el brazo y la separa de mi hermana y le dice:

-Ella es mi hija y lo que es con ella es conmigo. Luego la empujó tan fuerte que chocó contra la pared, estuvo a punto de rodar por el piso. La busca pleitos optó por abandonar el lugar y mas nunca molestó a mi hermana.

Mi padre mostrando una actitud comprensiva, mandó que la vaca la pasaran para otro potrero. Yo me alegré y noté que mi madre también.

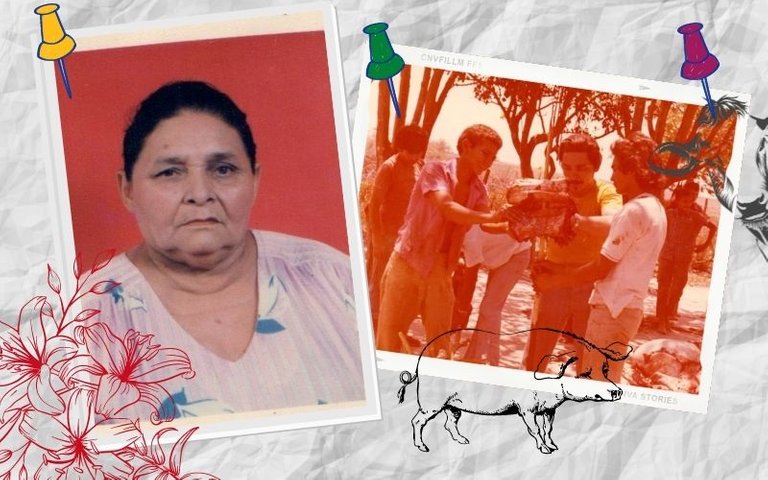

Mi madre se llamaba Rubina del Carmen Rodríguez. Años después mis abuelos se casaron, ella y todas sus hermanas y hermano cambiaron a Acosta Rodriguez. Fue la quinta hija de Doña Juana de la Cruz Rodríguez y la tercera de José Marcelino Acosta. Estudió hasta segundo grado en una escuela que había en el vecindario llamado El Platero, donde ella nació y se crio, a cargo de un maestro que atendía de primero a quinto grado. Comenzó el tercer grado el cual no terminó porque el maestro no volvió.

EL ENCUENTRO

Un día que mi padre iba a caballo para Totumito que es un caserío ubicado a orillas del Rio Sarare, al pasar frente a la casa de mis abuelos maternos ve a mi madre que estaba barriendo el patio, se paró, saludó y le pidió un vaso con agua. Se lo tomó, dio las gracias y siguió su camino.

De repente, había recorrido quizás 150 metros, se regresa y en un breve galope llega al falso de la casa y le pregunta a mi madre que todavía está en el patio:

-¿Cuál es tu nombre, catira?

Mi madre se queda mirando un poco desconcertada al desconocido por unos segundos. Luego responde:

-Rubina.

-Gracias Rubina por el agua-

Vuelve a su camino y emprende un galope más acelerado como tratando de recuperar el tiempo y espacio que invirtió al regresarse.

De regreso entró a la casa, saludó y preguntó por la catira Rubina. Mi madre era la más blanca de todas. Color que heredó de su padre. Una de sus hermanas fue y la llamó. Al estar presente dijo:

-¡A la orden¡ ¿Cómo está señor, cómo le fue? Regresó rápido.

-Entré para entregarle este pan que le traje de gratitud por el agua que me dió ayer. Si no es mucha molestia me regala otro vaso con agua y si tiene café también le recibo. Contestó mi padre.

Mi madre recibió el pan y salió en busca del agua. Al regreso, dijo:

-Gracias por el pan. Café no hay hecho, pero si espera un poquito le hago,

-Espero con gusto. Contestó mi padre. Al tiempo que bajaba del caballo agregó:

-El café hecho por una catira debe quedar bien sabroso.

-Sin duda. Contestó mi madre.

Mientras hervía el agua para colar el café. Mi madre volvió a la sala y le preguntó:

-Usted cómo se llama?

-Mi nombre es José Manuel Rondón, me crie con mi abuela Petra en el Hato San Lorenzo. Mi padre era Fabriciano Zapata Camejo. El ya murió. Mi madre es María Anastasia Rondón. Mi abuela la contrató para que le ayude en los quehaceres del hato, ella está muy mayor.

-¿Además de Rubina, tiene otro nombre? Preguntó mi padre.

-Mi nombre completo es Rubina del Carmen Rodríguez. Yo nací aquí y aquí me crie. En esta casa somos 10 personas ocho mujeres y dos hombres: mi papá José Marcelino y mi hermano Ramón Ignacio. Respondió mi madre.

En eso, una de sus hermanas anunció:

-¡Rubina el agua está hirviendo!.

- Voy a colar el café, ya vengo. Siéntese señor Rondon, dijo mi madre.

Después de tomar el café. Lo cual hizo bien despacio, como para estar más tiempo. Dijo:

-Gracias catira Rubina por el café, está sabroso. La próxima vez que venga no pido agua, pido café. Dentro de cinco días vuelvo a Totumito a buscar las cosas que compré para llevar al Hato para el trabajo de llano. Me guarda café.

-Y usted me trae pan, replicó mi madre.

De ahí en adelante las visitas de mi padre eran casi todos los fines de semana. A veces pernoctaba durante uno, dos o más días.

LA PARTICIÓN

Doña Petra Muere y después del novenario, comenzaron los preparativos para la partición. Para hacer el inventario del ganado, el trabajo de llano tardó más de tres meses. Ahora las visitas se hacían a intervalos de 10, 15 o 20 días. Mi madre reclamaba por qué tanto tiempo de una visita a otra. Mi padre se excusaba que era por el trabajo que estaban realizando.

Terminó la partición y mi padre recibió, por acuerdo de los hermanos herederos, 20 reses y un caballo. Todos los hijos no reconocidos recibieron esa cantidad de animales. Ahora el conflicto era para dónde llevar esos animales, pues no recibieron tierras. Un amigo de mi padre, que después fue mi padrino, le ofreció en venta una casa y un cuarto de legua de sabana que había recibido en herencia, conocido como el Fundo La Mapora. Mi padre compro la casa y las tierras. Arregló los potreros y la casa. Al poco tiempo, se llevó a su catira Rubina del Carmen a compartir las buenas y las no tan buenas en La Mapora.

En ese fundo nací yo, un 20 de mayo del año 1943. Mi papá cumplía los 23 años el 17 de junio y mi mamá cumplió ese mismo día 14 años. Ese fue su regalo. Allí mi madre terminó de aprender, por ensayo y error, el resto de labores que corresponden a una mujer en su hogar. Recuerdo que mi abuelo materno nos visitaba varias veces al año y nos acompañaba por largas temporadas sobre todo cuando mi padre andaba trabajando llano en los hatos o arriando ganado que llevaban para el Táchira. Mi abuela Juana también nos visitaba pero con menor frecuencia.

Mi padre cuidó muy bien las reses que le dieron. Consiguió con un dueño de hato vecino que le prestara un toro cebú para mejorar la raza del ganado. Los toros criollos los capó y le dejó la exclusividad al cebú de montar las vacas. El toro lo tuvo por dos años. De esa manera logró mejorar el pedigree del ganado. Para consumo interno sacrificaba vacas viejas que ya no eran productivas. Cuando vendía un toro se compraba dos o tres mautes o novillas. Así mejoró e incremento su rebaño.

La casa era de bahareque y el techo de palma a dos aguas. Recuerdo que cuando llovía torrencialmente y mi papá no estaba en casa, yo me bañaba con el agua que bajaba del techo y en el patio patinaba sobre el barro que se formaba, otras veces me lanzaba de barriga como emulando un salto largo. Ponía troncos de madera para medir la distancia que rodaba. Lo bueno de todo esto es que nunca me enfermaba. Andaba descalzo desde que me levantaba hasta que me acostaba. Las alpargatas me duraban mucho porque casi nunca me las ponía.

AHORA DUEÑO DEL FUNDO GUAFITA

Cuando murió mi tío David del Carmen, mi padre le compró a mi tío Jesús del Carmen Zapata Rondón la parte que le correspondía por herencia con lo cual sus bienes en ganado y en tierra se incrementaron. Quedando mi padre como único dueño del Fundo Guafita.

Cuando ocurrió todo esto mi madre, mis hermanas y yo estábamos en Barinas. Yo me enteré cuando regresé después de cuatro años y medio aproximadamente. Mi padre se había radicado en Guafita, a la Mapora iba esporádicamente. Nombró un encargado que cada 15 o 20 días subía a Guafita a entregar cuentas a mi padre, retirar la provisión de alimentos y el pago cuando correspondía. En Guafita vivía con Guillermina del Carmen Rodríguez, con quien tenía dos hijos.

El mismo año que nos fuimos para Barinas mi padre se llevó para La Mapora a Blanca Celina, una joven tachirense, blanca, simpática. Cuando la conocí ya le había dado tres hijos. Con el tiempo el número de hijos con ella llegó a 10.

En La Mapora compró varios derechos de sabana con los cuales sus hectáreas se incrementaron. En Guafita le compró al dueño del Hato El Torreño un lote de casi mil hectáreas.

Mi padre apenas aprendió a leer y escribir. Desde muy joven demostró ser muy responsable y serio en los negocios. Eso le permitió comprar varios derechos de sabana a crédito. A todos les pagó. Cuando ocurre su fallecimiento era un hombre solvente. No tenía deudas pendientes. Una de sus principales fortalezas era el crédito que tenía con el comercio de Guasdualito. No tuvo una cuenta abultada en el banco, pero si muchas puertas abiertas. Se decía que mucha gente le debía dinero, pero de eso no había evidencia. Para él la palabra tenía mucho valor

LLegaste hasta aquí, gracias por leerme

Pronto la continuación

English version

WHO WERE MY PARENTS

I was gathering the calves, as I did every day, when the deer sun was at its peak. I was shouting and humming one of those rhythms intoned by the "llaneros" (people from the plains) during the time of work on the plains. I was seven or eight years old when I was doing very well and I had a lot of fun running after the calves. The paddock was not very big. I don't think it was more than two hectares. Since it was the smallest paddock, we called it the little paddock. In the mornings, after milking the cows, my father would say to me:

-Son, plow the calves into the little paddock.

Other times:

-Lock my saddle horse that is in the paddock. Also: -Lock the beasts that are in the paddock in the corral.

-Run! Run! Run! Run! Run! Run, boy, the cow is catching up with you.

-The cow! -The cow! The cow! shouted another

Alarmed by the screams, I looked back and realized that a recently calved cow was coming at me with all her fury. Without thinking twice, I ran away to avoid being overtaken. As I was about to reach the fence of the paddock, I saw out of the corner of my eye that the cow was still following me. In the last 10 meters I increased my speed and with a leap, worthy of Olympic competitions, I ran over the fence without touching it, with the same speed that I fell I got up and ran towards the corral, as the gate of the fence was closed, I jumped and ran through two fences. I had not yet got up from the ground when I heard the noise that the cow made when it violently crashed against the gate. I was paralyzed for a few seconds and then I ran for safety.

There are cows that are very jealous when they have just calved and if you pass close to the calf they will charge at you. I have had this experience on other occasions, but it was not as compromising as on this occasion. The people who were watching the scene began to laugh and make jokes that I did not like. My mother said:

-I was praying to the virgin that the cow would not go and gore my boy.

Another wondered:

-I can't explain to myself how Baudilio got between the two trancas. I don't think he even touched them. Did you get hit? he asked me.

- No, I didn't feel any blow. Not even when I jumped over the fence wire. I remember I turned around and stood still, that's why the cow didn't reach me that way.

-When I ran towards the fence, I saw a light between two fences and I jumped through it.

Calmer now, I observed the height of the fence and felt an internal emotion for having jumped a height greater than one meter; I immediately shivered too as I imagined the worst if the cow had caught up with me. I said silently: luckily the gate was closed. Then I thanked God for being safe and sound.

THE IDENTIFICATION

My mother couldn't get over her astonishment. She was a pretty white woman, a little taller than my father. At that moment I observed her teary eyes, tears appeared in her green eyes. She came up to me and hugged me. She gave me a protective hug that I still remember. When he leaned down to hug me, I felt his long black hair caress my head and face. I, too, gave him a grateful son hug.

My father was a little further away talking to two gentlemen. He was laughing and at the same time praising the way I had emerged victorious from the dangerous situation. He added:

-Son, this is how one becomes a man in the llano. To become a complete llanero you have to live and experience many dangerous situations.

The gentlemen who were talking to my father, shared and approved what he said with affirmative head movements. One said: "It is true.

My mother didn't like my father's comment very much. I confess that I didn't like it either. I was expecting a support like the one my mother gave me. She said, at that time, that he had, at my age, lived through many dangerous situations. I heard him add:

-I, at Baudilio's age and size, was chased by a bull that head-butted me and threw me about five meters. I stopped and kept running all beaten up, without crying because in front of my grandmother Petra it was forbidden for a man to cry.

My father was a dark man of medium height. Always cheerful, good looking. People liked him very much, especially the ladies. He was what in the plains is called a man on horseback because he was very good at working on the plains. He had learned, under the tutelage of his grandmother Petra, everything a man should know about the plains.

My father used to say that when he went to work the plains he would pair up with a friend, brother or relative to rope the best bulls, he said he had fun showing off in that way. He knew how to rope very well. When they were in the corral for shoeing and marking calves, he was the first one to start roping. He would bull or tail if there was a need to do so. I saw him many times on the ranch, fighting animals that charged him. He would do it with the rope with his hat or with his shirt. On one occasion, when he was not wearing his hat or rope and without time to take off his shirt, with a skillful movement he eluded the bull that charged him, then grabbed him by the tail and when he was riding him he knocked him down. I applauded the feat and felt proud of my father.

-He said, "Rondón, put that cow in another paddock. It's a danger there when they go to pick up the calves.

My mother commanded, but in a loving voice. She was like that. When she had arguments with my father she never acted violently. Sometimes she seemed weak, but she was not. When she had to act, she did. On one occasion when we lived in the village a boy from the neighborhood attacked me, we got into a fight and my mother arrived with a boss and I thought she was coming to free me from the fight. He threatened to punish me if I didn't fight so that they would stop bothering me. The boy's mother wanted to intervene and my mother told her:

-Do not interfere yourself and if you want we can both grab each other. An invitation she did not accept. At that moment she was not the Rubina I knew.

My brother José Mercelino, his name was Marcelino but the clerk changed the "a" for "e", that's how it stayed, told me that while he was in a telephone exchange in San Carlos, Cojedes state, a lady came to bother my sister María Anastasia, the name my father gave her in honor of her mother. My sister told her not to bother her because she was on an important call for her. The lady insisted. My mother notices and gets up from the chair and pulls the lady by the arm and separates her from my sister and tells her:

-She is my daughter and what's with her is with me. Then he pushed her so hard that she crashed against the wall, she was about to roll on the floor. The troublemaker decided to leave the place and never bothered my sister again.

My father, showing an understanding attitude, had the cow moved to another pasture. I was happy and I noticed that my mother was too.

My mother's name was Rubina del Carmen Rodriguez. Years later my grandparents married, she and all her sisters and brother changed their names to Acosta Rodriguez. She was the fifth daughter of Doña Juana de la Cruz Rodriguez and the third daughter of Jose Marcelino Acosta. She studied up to second grade in a school that was in the neighborhood called El Platero, where she was born and raised, in charge of a teacher who attended from first to fifth grade. She started third grade which she did not finish because the teacher did not return.

THE ENCOUNTER

One day when my father was riding his horse to Totumito, a small village located on the banks of the Sarare River, when he passed in front of my maternal grandparents' house, he saw my mother sweeping the yard. She drank it, thanked him and continued on her way.

Suddenly, he had gone maybe 150 meters, he turns back and in a short gallop he arrives at the false of the house and asks my mother who is still in the yard:

-What is your name, catira?

My mother stares a bit puzzled at the stranger for a few seconds. Then she answers:

-Rubina.

-Thank you Rubina for the water.

She goes back on her way and starts a faster gallop as if trying to make up for the time and space she spent on her way back.

On his way back he entered the house, greeted and asked for Rubina the goat. My mother was the whitest of them all. A color she inherited from her father. One of her sisters went and called her. When she was present she said:

-At the order! -How are you sir, how did it go? She came back quickly.

-I came in to give you this bread that I brought you in gratitude for the water you gave me yesterday. If it is not too much trouble, give me another glass of water and if you have coffee I will also receive it. My father replied.

My mother received the bread and went out in search of water. When she returned, she said:

-Thank you for the bread. I don't have any coffee, but if you wait a little bit, I'll make it for you,

-I'll be glad to. My father replied. As he got off his horse, he added:

-The coffee made by a catira must be very tasty.

-No doubt. My mother replied.

While she boiled the water to brew the coffee. My mother returned to the living room and asked him:

-What is your name?

-My name is José Manuel Rondón, I grew up with my grandmother Petra in Hato San Lorenzo. My father was Fabriciano Zapata Camejo. He has passed away. My mother is María Anastasia Rondón. My grandmother hired her to help her with the chores at the ranch, she is very old.

-Does she have another name besides Rubina? My father asked.

-My full name is Rubina del Carmen Rodríguez. I was born here and I grew up here. In this house there are 10 of us, eight women and two men: my father José Marcelino and my brother Ramón Ignacio. My mother answered.

At that moment, one of her sisters announced:

-"Rubina, the water is boiling!

- I'm going to brew the coffee, I'll be right back. Sit down, Mr. Rondon," said my mother.

After drinking the coffee. Which she did very slowly, as if to stay longer. She said:

-Thank you catira Rubina for the coffee, it is tasty. The next time I come, I won't ask for water, I'll ask for coffee. In five days I go back to Totumito to pick up the things I bought to take to the Hato for the work in the plains. He keeps coffee for me.

-And you bring me bread," replied my mother.

From then on my father's visits were almost every weekend. Sometimes he stayed overnight for one, two or more days.

THE PARTITION

Doña Petra dies and after the novena, the preparations for the partition began. To make the inventory of the cattle, the work of plain took more than three months. Now the visits were made at intervals of 10, 15 or 20 days. My mother complained why so much time from one visit to another. My father excused himself that it was because of the work they were doing.

The partition was finished and my father received, by agreement of the sibling heirs, 20 cattle and a horse. All the unrecognized children received that amount of animals. Now the conflict was where to take those animals, since they did not receive any land. A friend of my father's, who later became my godfather, offered him a house and a quarter of a league of savannah that he had inherited, known as Fundo La Mapora. My father bought the house and the land. He fixed up the pastures and the house. Soon after, he took his wife Rubina del Carmen to share the good times and the not so good times at La Mapora.

I was born on that farm on May 20, 1943. My father turned 23 on June 17 and my mother turned 14 that same day. That was her gift. There my mother finished learning, by trial and error, the rest of the tasks that correspond to a woman in her home. I remember that my maternal grandfather visited us several times a year and accompanied us for long periods of time, especially when my father was working on the plains in the herds or herding cattle that were taken to Táchira. My grandmother Juana also visited us but less frequently.

My father took good care of the cattle he was given. He got a neighboring herd owner to lend him a zebu bull to improve the breed of cattle. He caparisoned the Creole bulls and gave the zebu the exclusive right to ride the cows. He kept the bull for two years. In this way he managed to improve the pedigree of the cattle. For domestic consumption, he slaughtered old cows that were no longer productive. When he sold a bull he bought two or three mautes or heifers. In this way he improved and increased his herd.

The house was made of bahareque and the roof was made of gabled palm. I remember that when it rained torrentially and my father was not at home, I would bathe with the water that came down from the roof and in the patio I would skate on the mud that formed, other times I would jump on my belly as if I were doing a long jump. I would put up wooden logs to measure the distance I rolled. The good thing about all this is that I never got sick. I walked barefoot from the time I got up until I went to bed. My espadrilles lasted a long time because I hardly ever wore them.

NOW OWNER OF THE GUAFITA FARM

When my uncle David del Carmen died, my father bought from my uncle Jesús del Carmen Zapata Rondón the part that corresponded to him by inheritance, which increased his assets in cattle and land. My father became the sole owner of Fundo Guafita.

When all this happened my mother, my sisters and I were in Barinas. I found out when I returned after about four and a half years. My father had settled in Guafita, he went to Mapora sporadically. He appointed a person in charge who went up to Guafita every 15 or 20 days to deliver accounts to my father, to collect the food supplies and the payment when it was due. In Guafita he lived with Guillermina del Carmen Rodríguez, with whom he had two children.

The same year we left for Barinas, my father took Blanca Celina, a young, white, nice girl from Tachira, to La Mapora. When I met her she had already given him three children. As time went by, the number of children with her reached 10.

In La Mapora he bought several rights of savannah with which his hectares increased. In Guafita she bought a lot of almost a thousand hectares from the owner of Hato El Torreño.

My father barely learned to read and write. From a very young age he proved to be very responsible and serious in business. That allowed him to buy several savannah rights on credit. He paid them all. When he passed away he was a solvent man. He had no outstanding debts. One of his main strengths was the credit he had with the commerce of Guasdualito. He did not have a large bank account, but he had many open doors. It was said that many people owed him money, but there was no evidence of that. For him the word had a lot of value.

You made it this far, thank you for reading me

I still have a lot to tell you

🔼 Banner y footer hecho en / Banner and footer made in canva.

🔽 Texto traducido en / Text translated in Deepl.

🔼 Separador hecho en / Separador made in canva.

🔽 Imagen de separador / Separator image Trotting Horse icono de Icons8