CARTAS A UN JOVEN POETA DE RAINER MARIA RILKE

Saludos, amigos de

@literatos. En mi post anterior para esta comunidad les hablé de las cartas y postales, una forma de comunicación que el mundo digital hizo desaparecer, por lo menos en la forma en que las escribimos varias décadas atrás, cuando las escribimos a mano y quien las recibía podía tardar buen tiempo en recibirlas y contestarlas, si las contestaba.

Así también les hablé sobre grandes artistas y escritores cuyas cartas se han conservado para la posteridad, y prometí comentar algunas de estas cartas. Inicio esta serie de textos dedicadas a las cartas con el poeta checo Rainer Maria Rilke, cuya obra en prosa y verso perdura en el tiempo por su profundo lirismo y sus hondas reflexiones acerca de la vida del espíritu.

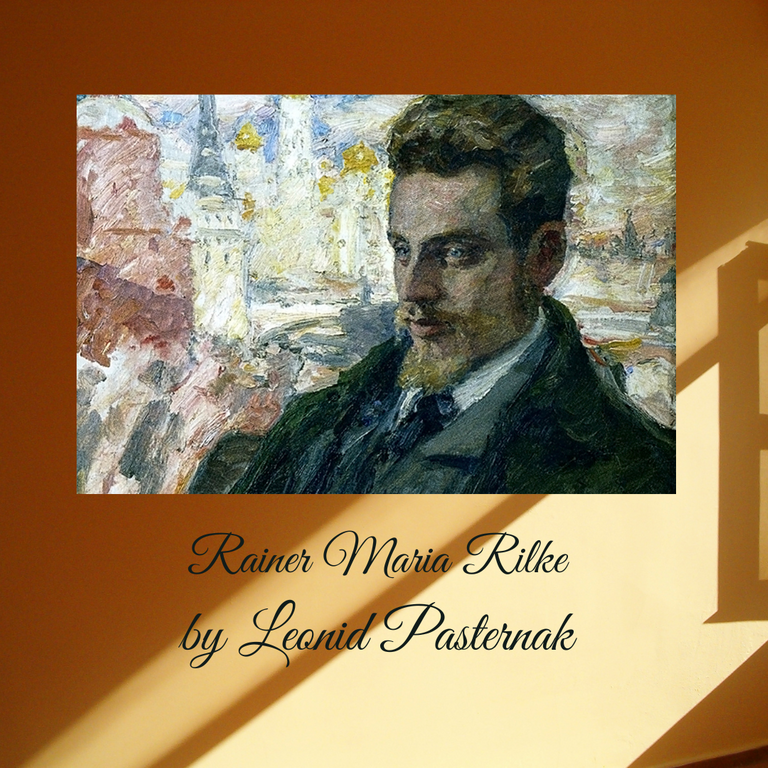

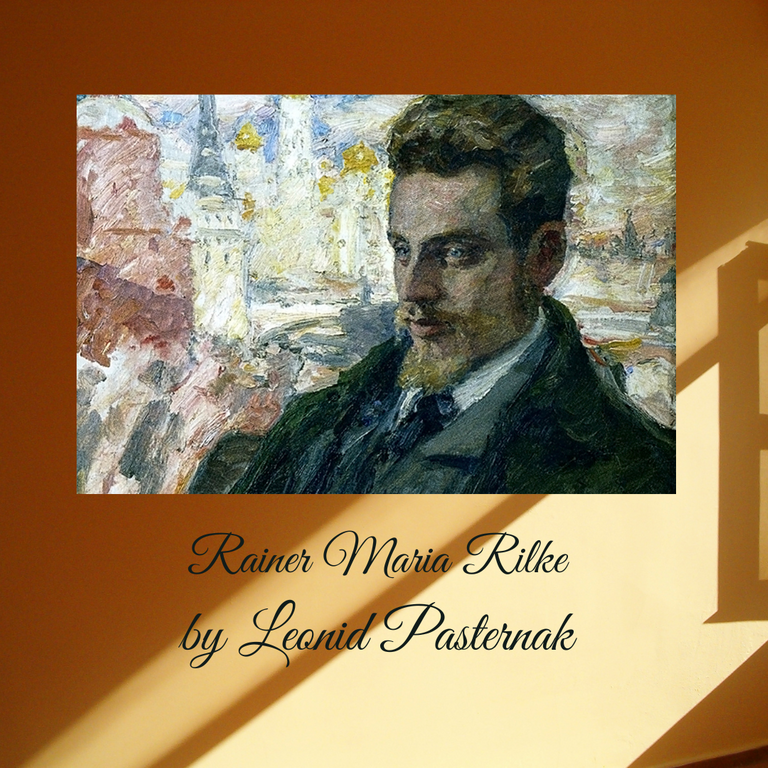

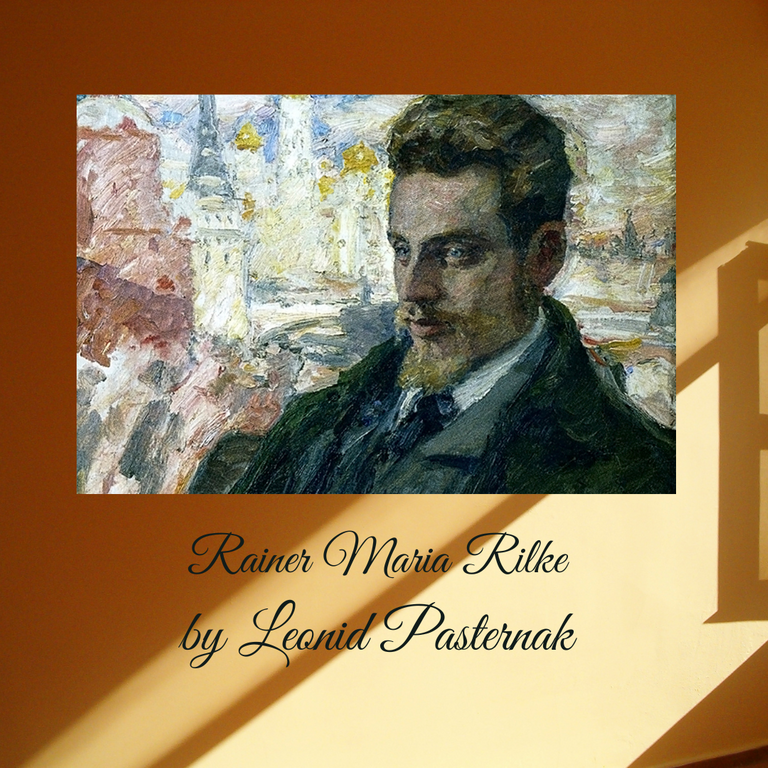

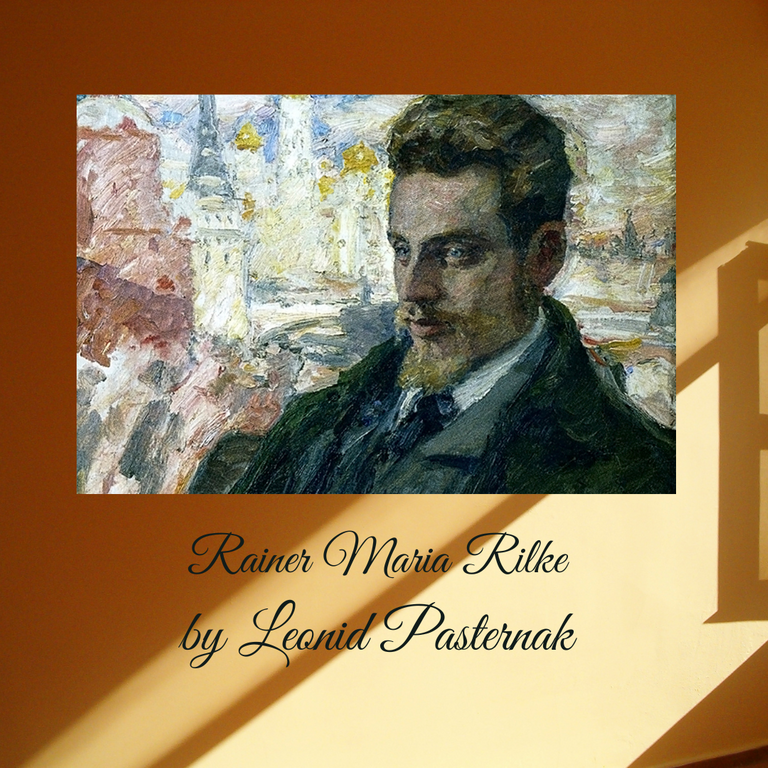

Sobre Rainer Maria Rilke

Rilke pertenece al periodo que conocemos como “Belle Epoque” (La Bella Época), que se inicia a finales del siglo XIX y termina al comenzar la Primera Guerra Mundial. Nació en Praga, que entonces era parte del Imperio austro-húngaro, el 4 de diciembre de 1875. En 1886 su padre lo obliga a ingresar a la academia militar, probablemente por encontrar a su hijo demasiado sensible, pero por razones de salud, abandona la milicia en 1891.

En 1895 inicia estudios en la Universidad de Praga, en la Facultad de Letras (HIstoria, Historia del Arte, Literatura y Filosofía) y a continuación en la Facultad de Derecho. Un año después conoce a su gran amor Lou Andreas Salomé y se traslada a Berlin, donde prosigue sus estudios. Pero en marzo de 1898 abandona definitvamente sus estudios, dedicándose enteramente a la escritura, e inicia una vida errante, que lo llevará a distintas ciudades.

Ese año, 1898, regresó a Praga, pero luego viajó a Italia (Florencia, Viareggio), para regresar nuevamente a Alemania. En 1899, viaja a Austria, regresa a Praga y luego viaja en compañía de Lou Andreas Salomé a Rusia (Moscú, San Petersburgo) y terminan el año en Alemania. Aunque regresan a Rusia nuevamente en 1900, regresando en verano a Alemania, donde el poeta conoce a Clara Westhoff, con quien se casa al año siguiente.

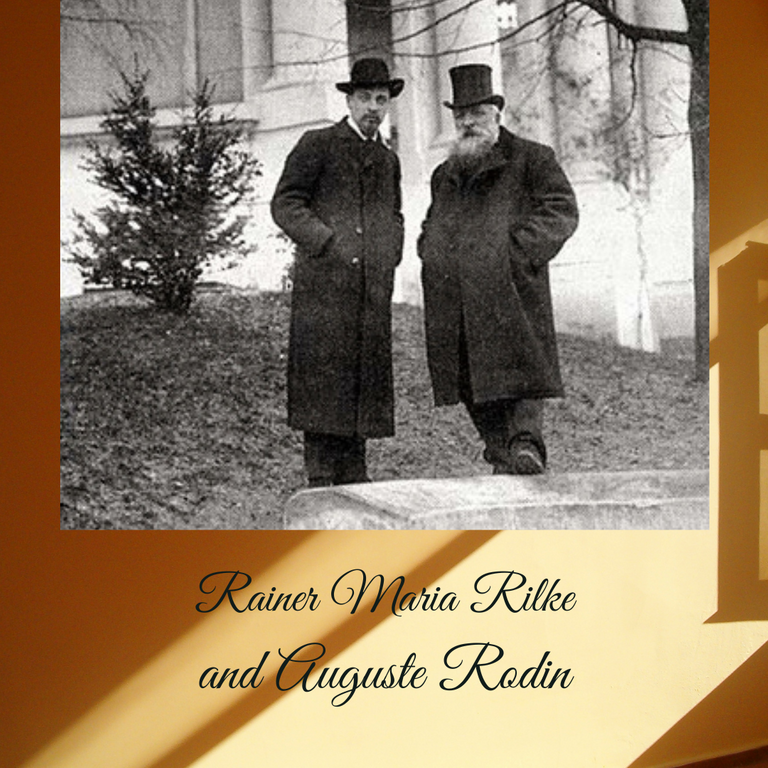

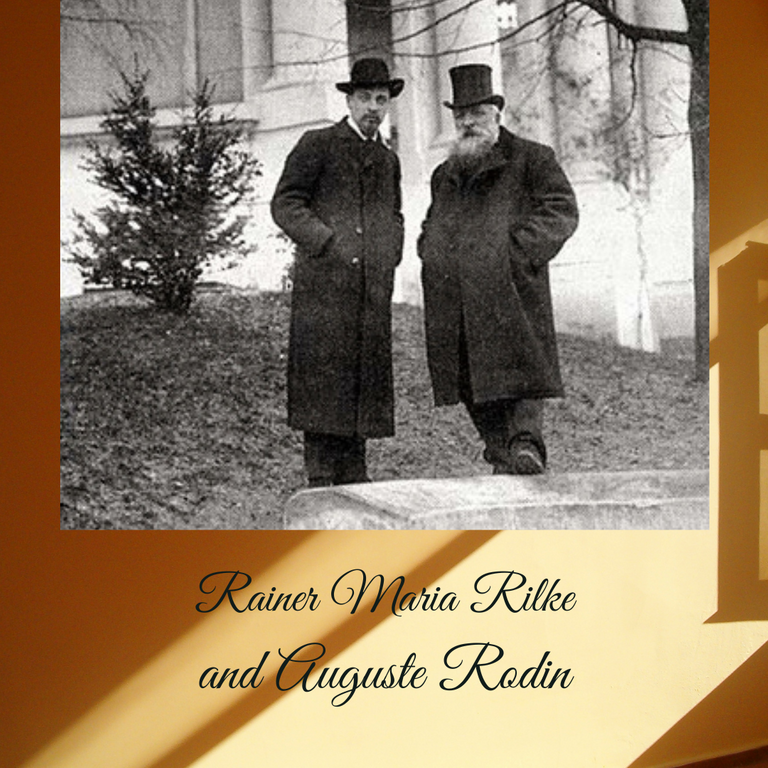

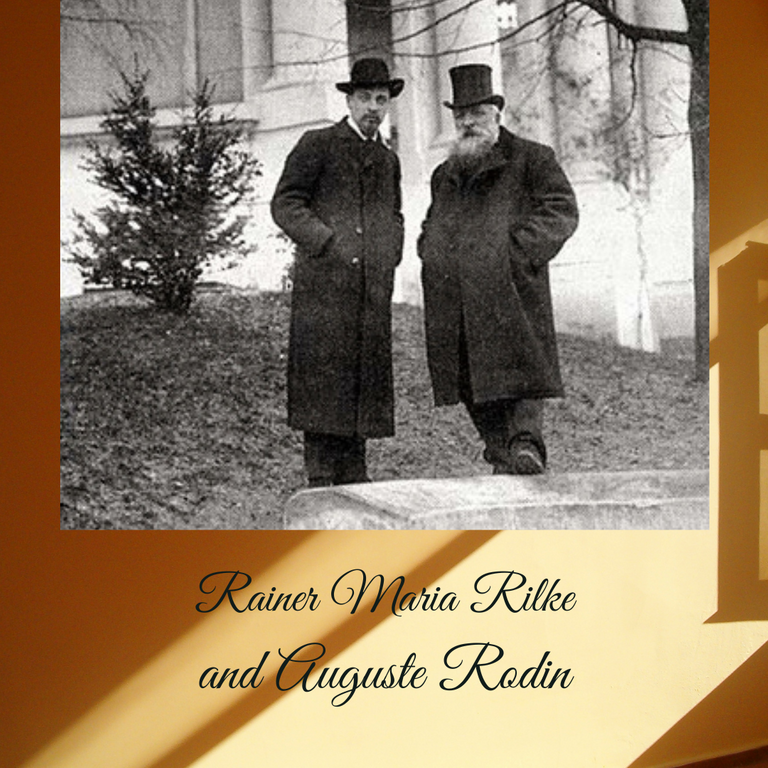

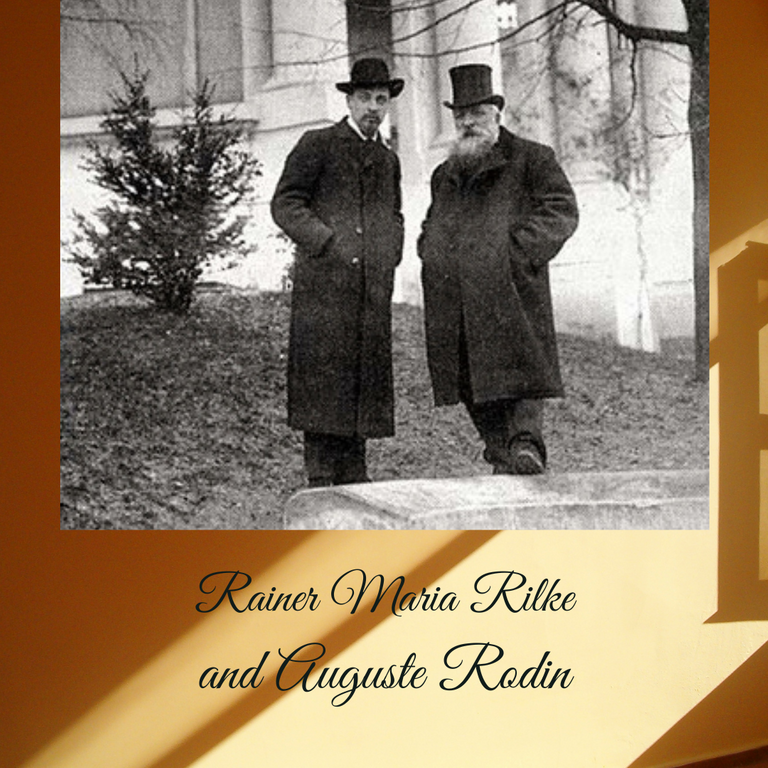

Aunque a finales de 1901 nace su única hija, Ruth, en 1902 se traslada a París, donde conoce al escultor Auguste Rodin, a quien admira, con quien vivirá y trabajará el año siguiente, luego de viajar por Italia, Alemania, Dinamarca y Suecia. En 1906 rompe su relación con Rodin y viaja nuevamente por Bélgica, Italia y Alemania. Los años siguientes continúa viajando. En 1911 conoce Egipto y luego se retira al castillo del Duino, de su amiga la princesa Turn y Taxis, donde escribe una de sus obras más importantes “Las Elegías del Duino”, de profundo contenido espiritual, en la cual reflexiona sobre la vida, la finalidad de la vida, el amor, la soledad y la muerte. Los años siguientes, a pesar de la Primera Guerra Mundial (1914-1918) sigue sus viajes por distintos países y ciudades y muere el 29 de diciembre de 1926 en Suiza.

Cartas al joven poeta Franz Xaver Kappus

La correspondencia con el joven poeta Franz Xaver Kappus se inicia en febrero de 1903, cuando Rilke le envía la primera carta, responde el envío de unos textos de Kappus, sobre los cuales pide opinión al poeta checo. La correspondencia entre ambos continúa a lo largo de ese año y finaliza en diciembre de 1908. En sus cartas Rilke aconseja a Kappus acerca de la vocación literaria y otros tópicos que le inquietan, sobre los cuales ha pedido consejo al poeta como el amor, la sexualidad.

Cuando iniciamos la vocación literaria nos embargan muchas dudas. Por lo general, si no pertenecemos a una familia o contexto cultural artístico, quienes nos rodean no suelen apoyar nuestra vocación por el arte o la literatura. Por el contrario, nos aconsejan dedicarnos a algo “productivo” y dejar nuestra vocación para el tiempo libre. La sociedad en general no ve la función social del arte y la literatura. La importancia que tiene para una sociedad sana la creación, la expresión estética. Por lo que es una gran suerte, en esos momentos iniciales de la vocación, poder contar con un mentor, alguien que nos guíe, nos de su apoyo.

Franz Kappus tuvo el gran privilegio de que el poeta Rainer Maria Rilke lo orientara y escribiera esas cartas que comentaré. Cuando era yo una joven estudiante de 17 años y comenzaba a escribir, quien era mi profesor de Castellano y Literatura, Mario Fernández, me prestó las obras completas de Rilke y me recomendó que leyera las cartas del poeta a Kappus. Uno de los consejos importantes que el maestro da al joven escritor es que no busque respuestas en el exterior respecto a si debe seguir o no su vocación, o si sus versos son buenos o no, le insiste en la primera carta que le escribe que debe buscar respuestas dentro de sí:

Pregunta usted si sus versos son buenos. Antes ha preguntado a otros. Los envía usted a revistas. Los compara con otros versos, y se intranquiliza cuando ciertas redacciones rechazan sus intentos. Ahora bien (puesto que usted me ha emplazado a aconsejarle), le ruego que abandone todo eso. Mira usted hacia afuera, y eso, sobre todo, no debería hacerlo ahora. Nadie puede aconsejarle ni ayudarle, nadie. Hay sólo un único medio. Examine esa base que usted llama escribir; pruebe si extiende sus raíces hasta el más profundo lugar de su corazón; reconozca si usted tendría que morirse si se le privara de escribir. Esto, sobre todo: pregúntese en la hora más silenciosa de la noche: ¿debo escribir? Excave en sí mismo, en busca de una respuesta profunda. Y si esta ha de ser de asentimiento, si usted ha de enfrentarse a esta grave pregunta con un debo enérgico y sencillo, entonces, construya su vida según esa necesidad (...)

El gran poeta le reitera a Kappus en varias de las diez cartas que le escribe la importancia de buscar en su mundo interior y no prestar atención a lo que le puedan decir quienes le rodean:

¿Qué he de decirle todavía? Todo me parece acentuado según es debido: finalmente, querría sólo aconsejarle todavía que vaya creciendo tranquilo y serio a través de su evolución: no podría producir más violento destrozo que mirando afuera y esperando de fuera una respuesta a preguntas que sólo puede contestar quizá su más íntimo sentir en su hora más silenciosa.

Así también le recomienda que no debe escribir poemas de amor, porque ese es un tema demasiado repetido, con una larga tradición, en el cual es muy difícil escribir algo propio. Le recomienda observar la naturaleza e intentar, “como el primer hombre”, “decir lo que ve y experimenta y ama y pierde”. Sobre todo le reitera escribir tomando como punto de partida su mundo propio, sus propias experiencias: “vuélvase a lo que le ofrece su propia vida cotidiana: describa sus melancolías y deseos, los pensamientos fugaces, y la fe en alguna belleza: descríbalo todo con sinceridad interior, tranquila, humilde, y use, para expresarlo, las cosas de su ambiente, las imágenes de sus sueños y los objetos de su memoria”.

En su segunda carta, además de reiterarle no prestar atención a las críticas externas, el maestro checo le recomienda al joven poeta, algo difícil para los jóvenes: tener paciencia, y describe la obra de arte con una palabra que usualmente se vincula a la mujer, a lo femenino, la gestación, que conlleva largos meses, mucho tiempo y paciencia. Leamos a Rilke:

No hay medida con el tiempo; no sirve un año, y diez años no son nada; ser artista quiere decir no calcular ni contar: madurar como el árbol, que no apremia su savia, y se yergue confiado en las tormentas de la primavera sin miedo a que detrás pudiera no haber verano. Pero lo habrá sólo para los pacientes, que están ahí como si tuvieran por delante la eternidad, de tan despreocupadamente tranquilos y amplios. Yo lo aprendo diariamente, lo aprendo entre dolores, a los que estoy agradecido. ¡La paciencia lo es todo!

Esta idea de la creación como un proceso de gestación interna se reitera en su tercera carta, “también en el hombre hay maternidad, me parece, corporal y espiritual; su engendrar es también una suerte de parir, y es parir cuando crea de su íntima plenitud”. En esa carta también le escribe sobre las relaciones entre hombres y mujeres, y paradójicamente, de la soledad del artista: “ame su soledad, y aguante el dolor que le causa, con queja de hermoso son”. En agosto de 1904 vuelve a hablar de la soledad, como una condición inherente del ser humano: “Volviendo a hablar de la soledad, aparece cada vez más claramente que ella no es en rigor, nada que se pueda tomar o dejar. Y es que somos solitarios. Uno puede querer engañarse a este respecto y obrar como si no fuese así; esto es todo. ¡Pero cuánto más vale reconocer que somos efectivamente solitarios, y hasta partir de esta base!”

Cuando yo era una joven estudiante tuve el privilegio de recibir varias cartas del poeta y cronista de Aragua Miguel Ramón Utrera, que algunos años después editó el poeta, gestor cultural y docente Efrén Barazarte con el título “Cartas espirituales”. En mi próxima entrada les escribiré sobre aquellas cartas del maestro Miguel Ramón Utrera y algunas de las recomendaciones que le hizo a la joven poeta que yo era entonces. Espero que hayas disfrutado la lectura del presente texto.

Te invito a leer el artículo previo sobre las cartas, "Cartas: una forma de comunicación perdida", con el cual presenté esta serie de textos que dedicaré a las cartas de escritores y artistas.

https://peakd.com/hive-179291/@beaescribe/cartas-una-forma-de-comunicacion-perdida-letters-a-lost-form-of-communication-spaeng

English version

LETTERS TO A YOUNG POET BY RAINER MARIA RILKE

Greetings, friends of

@literatos. In my previous post for this community I told you about letters and postcards, a form of communication that the digital world made disappear, at least in the way we wrote them several decades ago, when we wrote them by hand and whoever received them could take a long time to receive them and answer them, if he answered them.

I also spoke to you about great artists and writers whose letters have been preserved for posterity, and I promised to comment on some of these letters. I begin this series of texts dedicated to letters with the Czech poet Rainer Maria Rilke, whose work in prose and verse endures through time for its deep lyricism and profound reflections on the life of the spirit.

About Rainer Maria Rilke

Rilke belongs to the period we know as "Belle Epoque" (The Beautiful Age), which began at the end of the 19th century and ended at the beginning of World War I. He was born in Prague, which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, on December 4, 1875. He was born in Prague, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, on December 4, 1875. In 1886 his father forced him to enter the military academy, probably because he found his son too sensitive, but for health reasons, he left the military in 1891.

In 1895 he began his studies at the University of Prague, at the Faculty of Arts (History, History of Art, Literature and Philosophy) and then at the Faculty of Law. A year later he met his great love Lou Andreas Salomé and moved to Berlin, where he continued his studies. But in March 1898 he definitively abandons his studies, devoting himself entirely to writing, and begins a wandering life, which will take him to different cities.

That year, 1898, he returned to Prague, but then traveled to Italy (Florence, Viareggio), to return again to Germany. In 1899, he travels to Austria, returns to Prague and then travels in the company of Lou Andreas Salomé to Russia (Moscow, St. Petersburg) and they finish the year in Germany. Although they return to Russia again in 1900, returning in summer to Germany, where the poet meets Clara Westhoff, whom he marries the following year.

Although at the end of 1901 her only daughter, Ruth, was born, in 1902 she moved to Paris, where she met the sculptor Auguste Rodin, whom she admired, and with whom she lived and worked the following year, after traveling through Italy, Germany, Denmark and Sweden. In 1906 he breaks his relationship with Rodin and travels again through Belgium, Italy and Germany. The following years he continues to travel. In 1911 he visited Egypt and then retired to the castle of Duino, of his friend Princess Turn and Taxis, where he wrote one of his most important works "The Elegies of Duino", of deep spiritual content, in which he reflects on life, the purpose of life, love, loneliness and death. In the following years, despite the First World War (1914-1918), he continued his travels through different countries and cities and died on December 29, 1926 in Switzerland.

Letters to young poet Franz Xaver Kappus

The correspondence with the young poet Franz Xaver Kappus began in February 1903, when Rilke sent him the first letter, replying to Kappus's texts, on which he asked the Czech poet for his opinion. The correspondence between the two continues throughout that year and ends in December 1908. In his letters Rilke advises Kappus about the literary vocation and other topics that disturb him, on which he has asked the poet for advice, such as love, sexuality, etc.

When we begin our literary vocation, we are overcome with many doubts. Generally, if we do not belong to an artistic family or cultural context, those around us do not usually support our vocation for art or literature. On the contrary, they advise us to dedicate ourselves to something "productive" and leave our vocation for our free time. Society in general does not see the social function of art and literature. The importance of creation and aesthetic expression for a healthy society. So it is very fortunate, in those initial moments of vocation, to have a mentor, someone to guide us, to give us support.

Franz Kappus had the great privilege of being guided by the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who wrote the letters I am about to comment on. When I was a young student of 17 and was beginning to write, my Spanish and Literature teacher, Mario Fernández, lent me the complete works of Rilke and recommended that I read the poet's letters to Kappus. One of the important pieces of advice that the teacher gives to the young writer is that he should not look outside for answers as to whether he should follow his vocation or not, or whether his verses are good or not, he insists in the first letter he writes to him that he should look for answers within himself:

You ask if your verses are good. You have asked others before. You send them to magazines. You compare them with other verses, and you feel uneasy when certain editors reject your attempts. Now (since you have asked me to advise you), I beg you to abandon all that. You look outward, and that, above all, you should not do now. No one can advise you or help you, no one. There is only one way. Examine that base you call writing; test whether it extends its roots to the deepest place in your heart; recognize whether you would have to die if you were deprived of writing. This, above all: ask yourself in the quietest hour of the night: should I write? Dig into yourself, in search of a profound answer. And if it is to be one of assent, if you are to face this grave question with an energetic and simple must, then build your life according to that necessity (...)

The great poet reiterates to Kappus in several of the ten letters he writes to him the importance of searching his inner world and not paying attention to what those around him may say:

What shall I still say to you? Everything seems to me to be emphasized as it should be: finally, I would only like to advise you still to grow calm and serious through your evolution: you could not produce more violent destruction than looking outside and expecting from outside an answer to questions that perhaps only your most intimate feeling can answer in its most silent hour.

He also recommends him that he should not write love poems, because that is a theme too often repeated, with a long tradition, in which it is very difficult to write something of one's own. He recommends him to observe nature and try, "like the first man", "to say what he sees and experiences and loves and loses". Above all he reiterates him to write taking as a starting point his own world, his own experiences: "turn to what your own daily life offers you: describe your melancholy and desires, fleeting thoughts, and faith in some beauty: describe it all with inner sincerity, quiet, humble, and use, to express it, the things of your environment, the images of your dreams and the objects of your memory".

In his second letter, in addition to reiterating not to pay attention to external criticism, the Czech master recommends to the young poet, something difficult for young people: to have patience, and describes the work of art with a word that is usually linked to women, to the feminine, gestation, which involves long months, a lot of time and patience. Let us read Rilke:

There is no measure with time; a year is no good, and ten years are nothing; to be an artist means not to calculate or count: to mature like the tree, which does not press its sap, and stands confidently in the storms of spring without fear that there might not be a summer behind it. But there will be only for the patients, who are there as if they had eternity ahead of them, so carefree, calm and spacious. I learn it daily, I learn it among pains, to which I am grateful. Patience is everything!

This idea of creation as a process of internal gestation is reiterated in his third letter, "in man there is also maternity, it seems to me, corporal and spiritual; his engendering is also a kind of giving birth, and it is giving birth when he creates from his intimate fullness". In this letter he also writes about the relations between men and women, and paradoxically, of the artist's loneliness: "love your loneliness, and endure the pain it causes you, with complaints of beautiful are". In August 1904 he speaks again of loneliness, as an inherent condition of the human being: "Speaking again of loneliness, it appears more and more clearly that it is not strictly speaking, nothing that can be taken or left. And the fact is that we are solitary. One may want to deceive oneself in this respect and act as if it were not so; that is all. But how much better it is to recognize that we are indeed solitary, and even to start from this basis!

When I was a young student I had the privilege of receiving several letters from the poet and chronicler of Aragua Miguel Ramón Utrera, which some years later were edited by the poet, cultural manager and teacher Efrén Barazarte under the title "Spiritual Letters". In my next post I will write about those letters of the master Miguel Ramón Utrera and some of the recommendations he made to the young poet that I was then. I hope you have enjoyed reading this text.

I invite you to read the previous article on letters, "Letters: a lost form of communication", with which I introduced this series of texts that I will dedicate to the letters of writers and artists.

https://peakd.com/hive-179291/@beaescribe/cartas-una-forma-de-comunicacion-perdida-letters-a-lost-form-of-communication-spaeng

Soy la autora de este artículo, las imágenes y los separadores que lo ilustran fueron diseñadas por mí en canva.com en su versión gratuita. La traducción es de

https://www.deepl.com/ I am the author of this article, the images and dividers that illustrate it were designed by me on canva.com in its free version. The translation is from

https://www.deepl.com/