The other day, I really enjoyed this interview with social commentator and actress Brett Cooper from The Daily Wire. There's a lot to be found in this girl's story, her career changes and the integrity she seems to possess despite her young age (she just turned 23). One thing I particularly liked was, talking about her experience as a homeschool kid, she has no qualms about admitting that yes, she grew up a little weird.

It's a big talking point in the homeschooling debate - if I educate my kids, won't they miss a crucial social element that's present in public education? Won't they turn out a little unusual? Yes to both. However, I've never thought of those points as arguments against homeschooling.

While there is a lot of value in being exposed to the social dynamics of the schoolyard, I don't think it's a mandatory aspect of a child's rearing. We're seeing more and more mental health and behavioral issues with traditionally schooled children, not to mention that we are living through a crisis of loneliness and isolation among young adults, the majority of whom were schooled in the public system. To me, that only goes to show that while socializing in the schoolyard has its benefits, it's by no means an easy guarantee to getting an outgoing, confident, socially-agreeable kid.

(Well, actually I do believe traditional schooling rewards agreeableness and placidity, though I don't think that's what we want of future generations.)

What I liked about Cooper's confidence was that for a long time, the much-harangued homeschooling community has been running from that suggestion of weirdness in our children. No no, we try to argue, they're like everyone else. We're trying to blend in, so to speak, to minimize the perceived drawback that the mainstream makes homeschooling out to be. (And for good reason, in many countries in Europe, homeschooling can be a dangerous choice.)

Except. Of course your kids are gonna turn out unusual and different from the mass-educated kids. Because you're educating them as if they were individuals, something the public system is very bad at. Presumably, these kids are encouraged to a much greater extent to pursue their passions and interests and talents, which is not something that we see much of in the public, one-size-fits-all schooling tank.

So obviously they're going to be a little unusual. Now, the extent of that unusualness will likely depend on the type of schooling they received, with children growing up in unschooling families that deviate from the typical curricula leaning towards the more unusual end.

"Unusual" is not a bad thing.

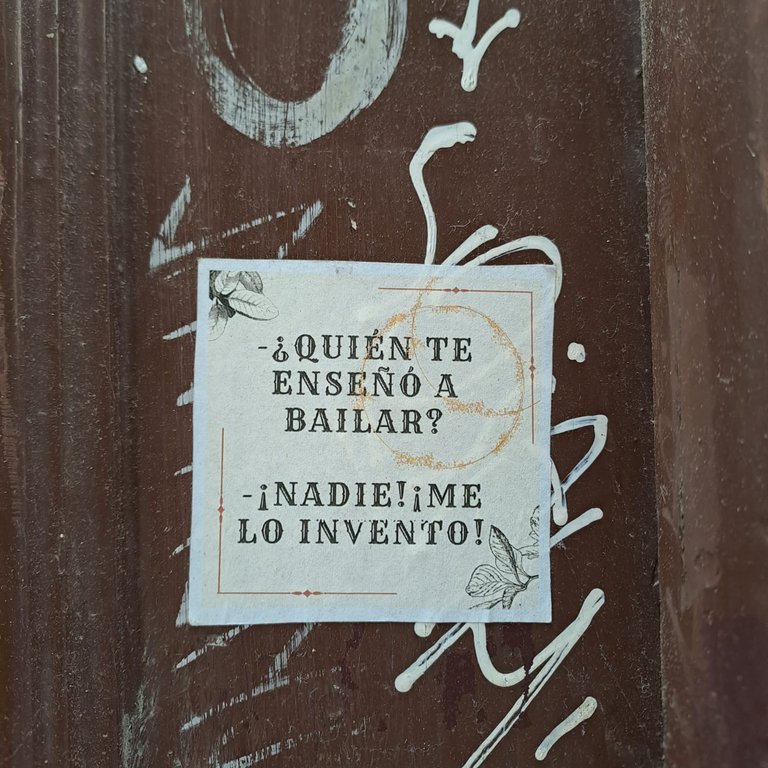

"Who taught you to dance? No one, I made it up.

It's merely saying you're an individual. Which you are, and which children need to be reminded of firmly during these very important developmental years.

One other aspect that Brett was pointing out that I resonated with was the value of having children interact with people of ages other than their own, something you again don't really see in school, where the majority of the time, your kids are with other children of a similar social background, typically older or younger by only 1-1.5 years.

That's not nearly enough variety for a child's development. As Peter Gray points out in his groundbreaking "Free to Learn", this was one major benefit of hunter-gatherer societies where children were raised together with all the other children of the group, so there was a wide range of ages. And where older children were invited to participate in tasks alongside adults. It's undescribably useful for a child to interact with older children, which creates a hierarchy and family-like structure. It teaches kids to speak to and relate with children much older than themselves that they (in a traditional schooling system) would be intimidated and shunned by. It's also vital for older children to have young kids around them as it engenders responsibility, leadership, etc.

As a teen, I frequently found myself the youngest in a group, since I was involving myself in various workshops, courses and projects that typically involved adults (ranging from student-aged to retirees). It was hugely intimidating at first, coming from a traditional schooling background, but also very useful I thought for my social development.

I see a big difference here between myself and my peers who still, even in their mid-twenties, are interacting with older people as just that. Older kids. Not on an equal playing field at all, either showing them an undue and silly amount of reverence or otherwise dismissing them as "old".

That's not a mark of good social development, in my book.

I also see a lot of suffering in people my age arising from the need to conform, to belong. A lot of suppression of their truer selves perhaps, or else a stillbirth at that level. Having never been encouraged to develop their individuality, they conform quite easily, but there is a certain sense of absence in them. And how could there not be? Man's aim in life is to outline and flesh out that self.

So coming back to the socialization question that some people so haughtily throw in homeschoolers' faces, I'd say for one thing, I'd like to see some kids in traditional schooling who are individuated and actually socially well-integrated (which isn't to me just a large social clique to go to the mall with). For another, I don't see why homeschooled children would automatically become outcasts and fringe-dwellers. If it's worth doing, as a parent, it's worth doing right. If you want to home-educate your kids, it seems to me you should provide them also the social resources and outlets to mitigate that difference (which is all it is really). But that's not really a problem, most people I know in this sphere do that quite well. '

I think there's more loneliness to our lot, but I think that's also linked with what I was saying before. Children who are treated as individuals do tend to have a better sense of who they are, what they like and dislike and a diminished incentive to follow the herd. Of course it's going to be lonelier.

Wes & Grindan

Wes & Grindan