Joan Miro is one of the biggest, strangest names in the world of art, that's for sure. While many come to Barcelona for the Gaudi sculpture, I'd say for me, the Joan Miro Foundation was hands-down my favorite art-related discovery of the entire trip. Very close in the running with the Picasso Museum, which had the added benefit of being free on the first Sunday of the month. Yet still, I found myself falling in love with Miro in a way I seldom do.

I'm not a snob when visting museums. I don't care for the let's ooh and aah in front of this random fat guy's portrait for ten minutes (even if we have no clue who he is and won't look it up when we get home). I try to keep space to be moved and booking my ticket for the Foundation, I didn't know I would be. I knew little of Miro and wasn't crazy about his art, what I'd seen of it. I thought he belonged to that excessively childish naive sect of artists that doesn't typically do it for me.

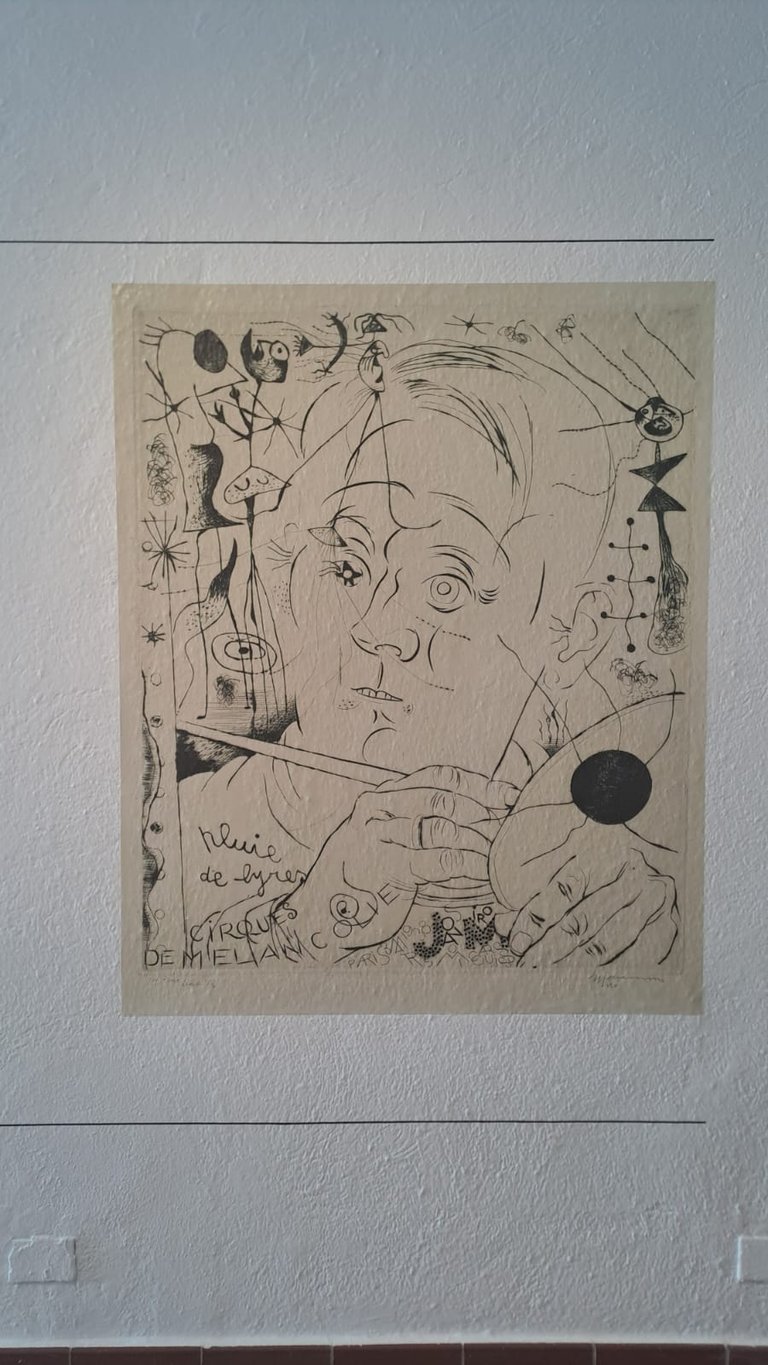

Still, reading about his opposition to the Franco regime and open antagonism towards it (as was the case with Picasso and many other artists of the time), I figured I owed it to the guy. He seemed like a decent man. He even looked like a decent man, though the only picture I have of him is this self-portrait.

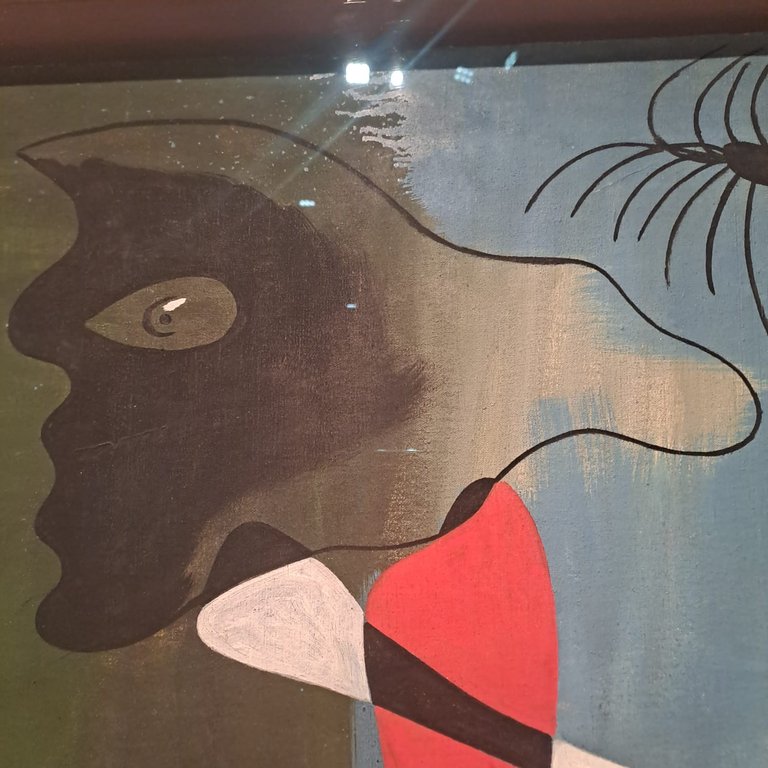

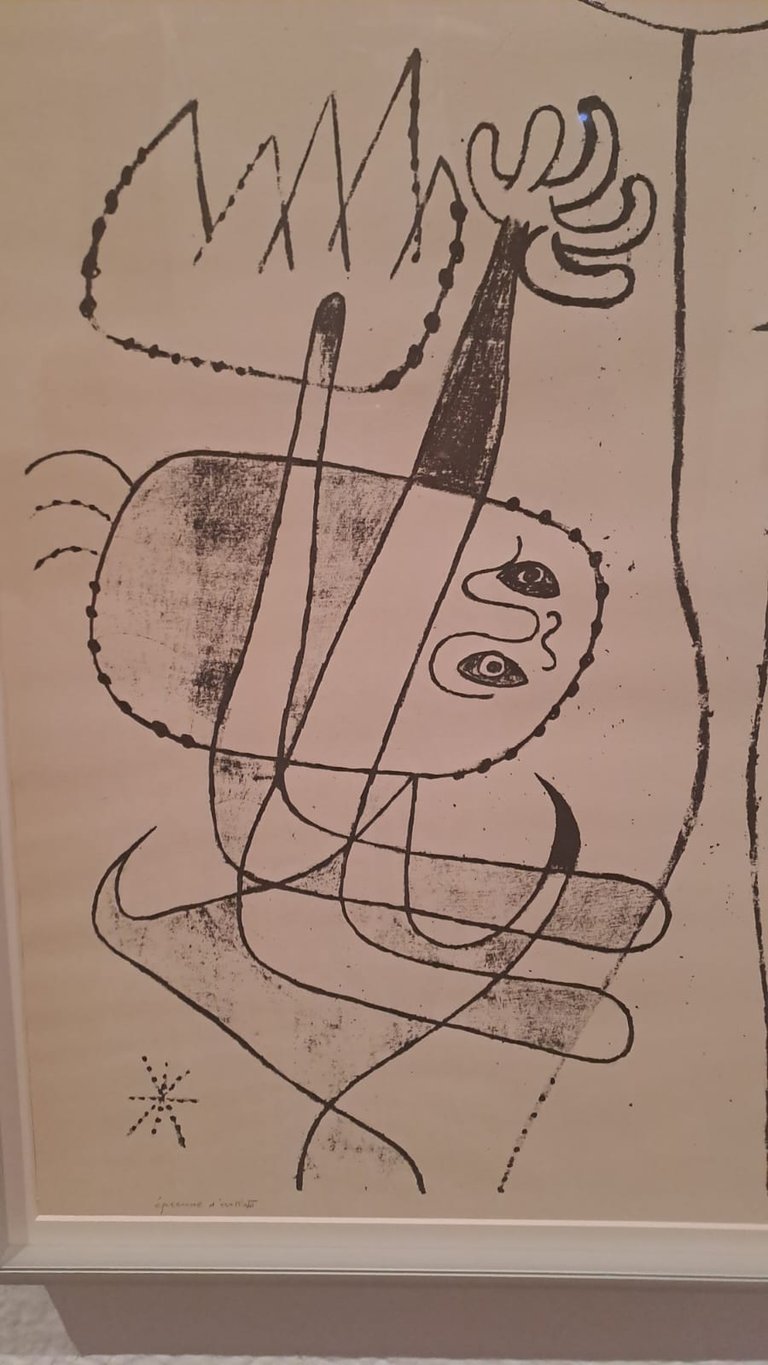

Pretty fucking brilliant. They had displayed several versions of the portrait side-by-side, as well as a video showing the evolution of the portrait. It was interesting to me that while some parts became blown out of proportion, in Miro's signature style, the general outlines of the artist's face disappeared with every new addition. It became less about what the man looked like, but what the interior of his mind was like.

And if there's one thing can be said about Miro, it's that he had a pretty fantastic mind.

In his own words, his concern with his art was to challenge every school and concept that had gone before. He quite directly said that while he understood and appreciated the value of traditional techniques like chiaroscuro, he simply did not want them in his art.

Miro spent decades channeling his imagination, his dreams. He wanted to make art that didn't look like art. He hoped his paintings to be "what poetry would look like put to music by a painter" (I think I got the quote right. Imagine that.

He made a religion out of art, and came back constantly to improve it. Miro seemed to believe that art is never done and that one could and should return to it as the artist himself changes through time, and alter it as he sees fit.

What a fascinating concept, and a challenging one. Challenging as hell. I find often, looking through my writing, that there are pieces I can very clearly pinpoint to one period in my life. Both stylistically and in terms of the themes. But what if you went back to them constantly, and if a theme no longer interested you, you simply painted over it?

It might be a fun experiment, to return to a short story every few years and keep versions. Compare it at the end of thirty years and see if it's recognizable. We tend to assume the work is done when we originally say it's done. But how can it be when we ourselves never are?

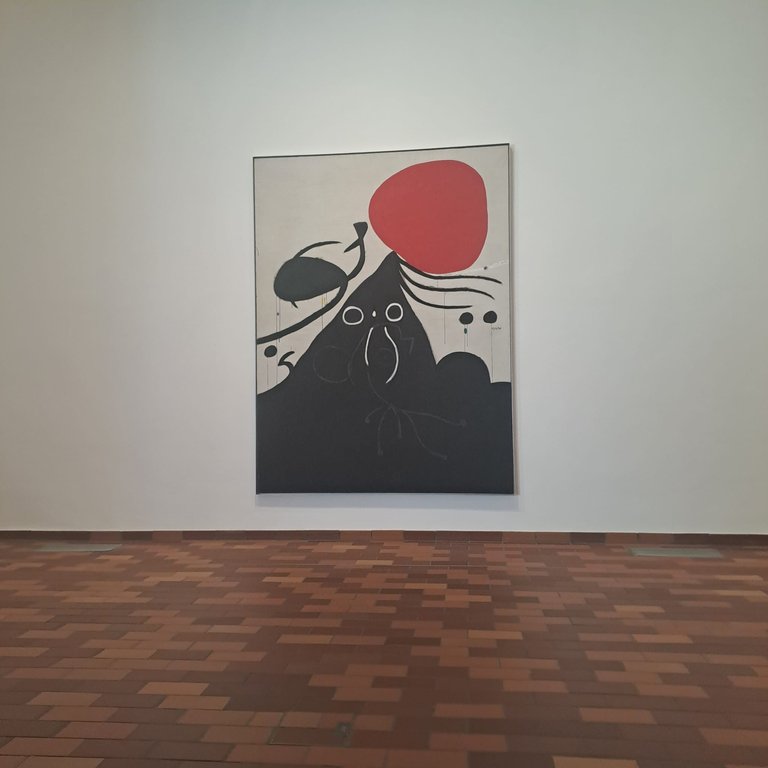

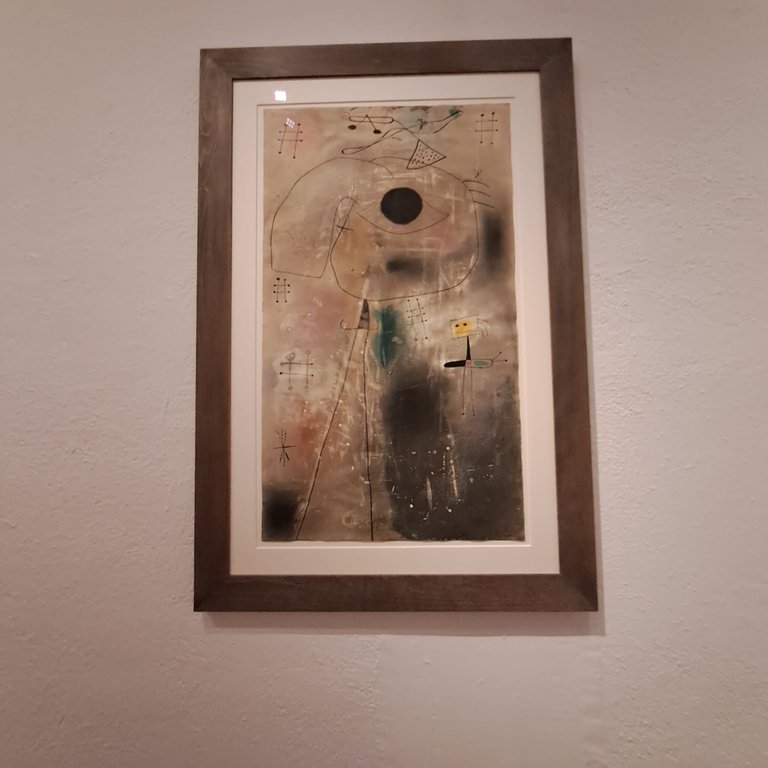

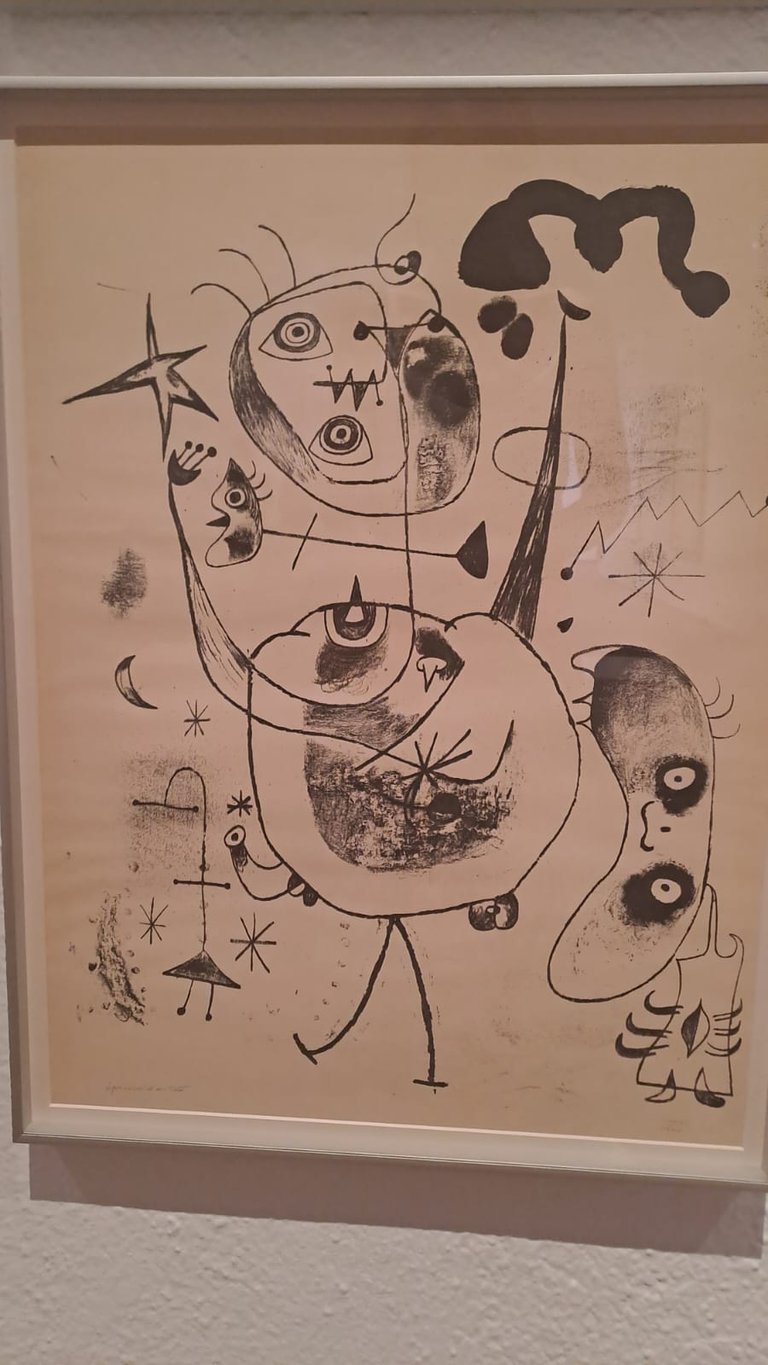

Miro himself frequently returned to female figures, as he interpreted them, as well as birds and celestial motifs. Both of which served as a pretty cut and dry symbol for the freedom that, for much of Miro's life, was absent from his native and much-loved Spain.

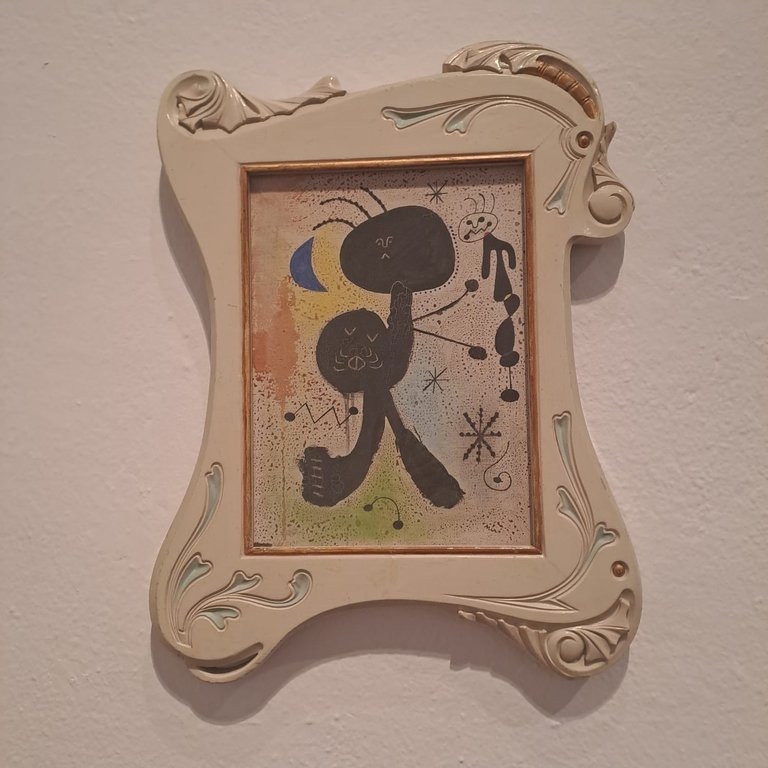

One of seemingly endless variants of woman dreaming of the heavens. Obsessively, Miro's characters longed for escape (if not on earth, at least in the celestial realm.

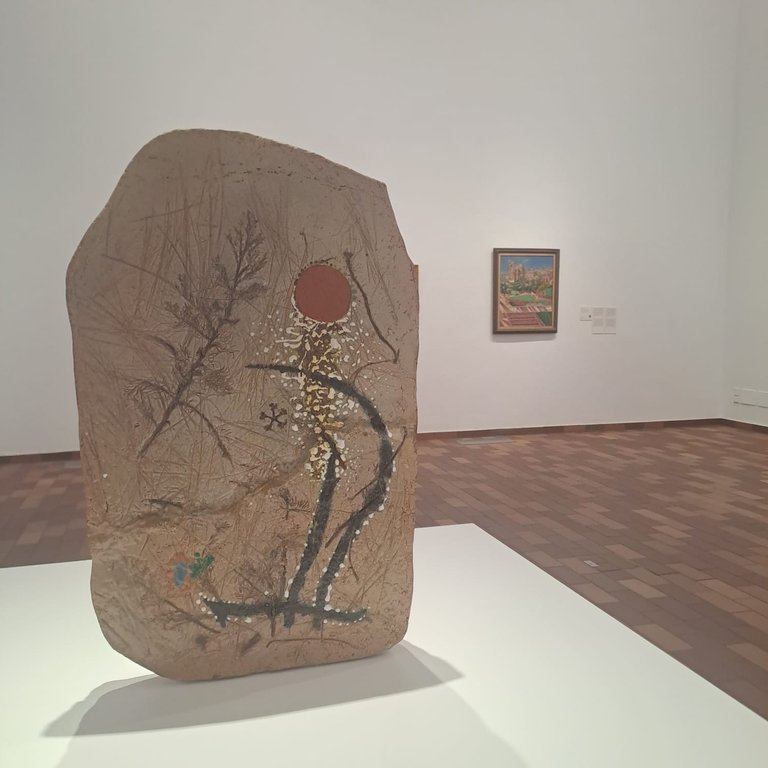

Reaching, also, was a common element of Miro's work.

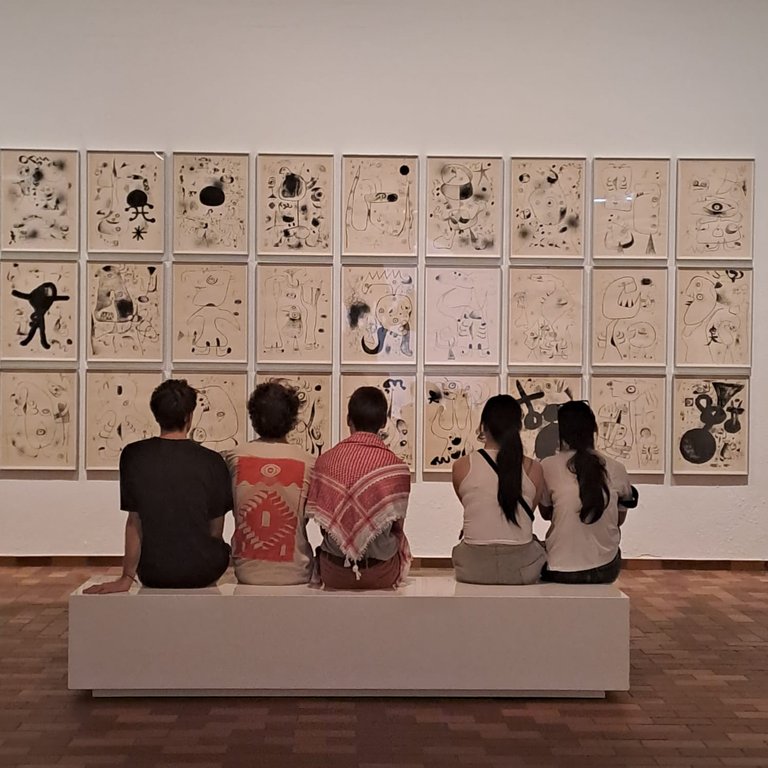

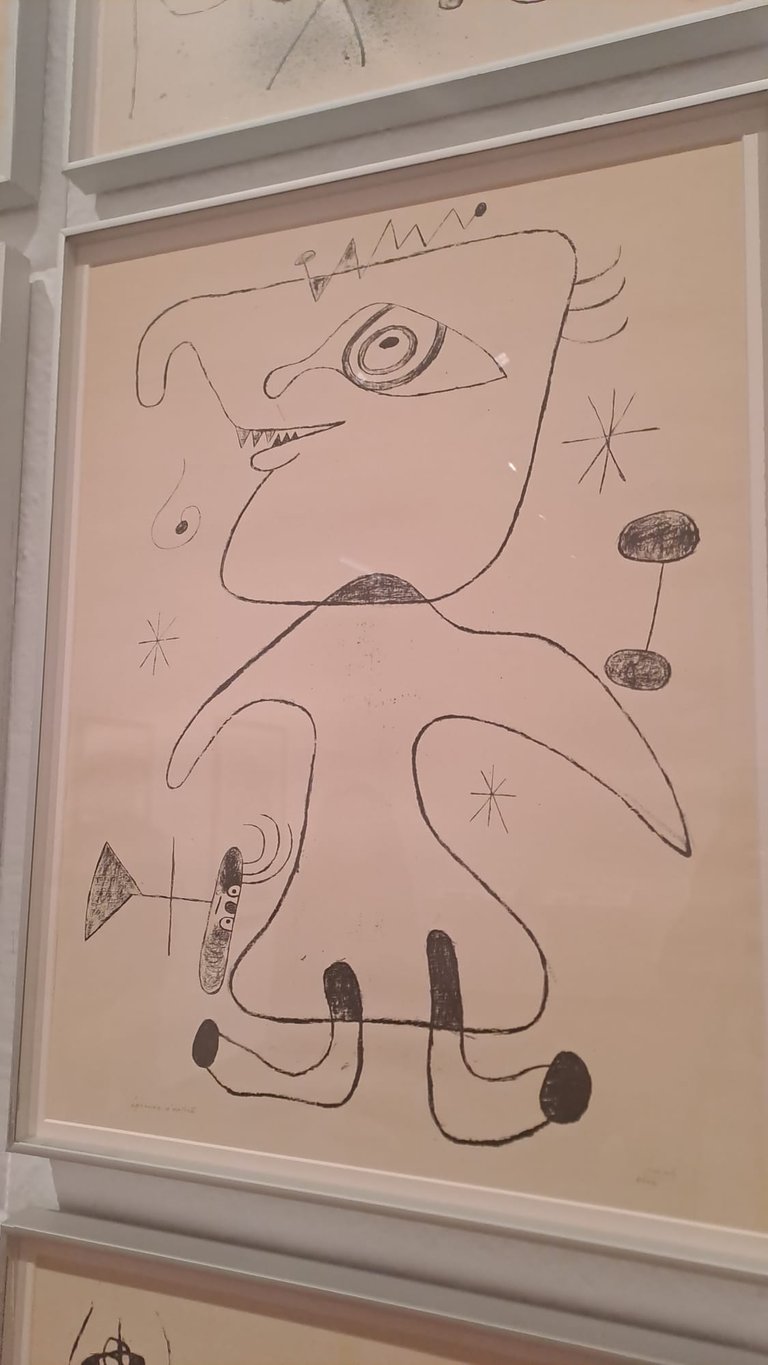

Like many of the great artists of his time, Miro outgrew quite early that phase of an artist's life where he's concerned with faithfully reproducing the world he sees. Rapidly, he became concerned with his inner world, his imagination. Whenever the "real world" was represented (as in this series of very-popular post-civil-war sketches, it was Miro's very distinct perception of the world and its outstanding elements.

What seems fascinating to me is that (at least to some people) such art is much more expressive and meaningful than faithful reproductions. It is similar, I think, to literary creation. When you write a story, you try to pick out certain elements that stand out to you from your real life experience, then pepper them through your text to lend it credibility.

My favorite of the series. Look how hopeful he seems, despite the brutal regime.

Arguably, if you described in detail how your character sliced the bread, waited for the butter to warm, had trouble separating the ham slices, etc., it would be a lot more realistic than if you zeroed in on a single detail of what he's doing, like the scotch tape peeling off the corner of the table and grinding against his forearm. And yet,it's much likelier you'll lose the reader if you go for the play-by-play.

Miro's art felt like that. Not like he was trying to get me to see every last detail, rather like he was leaning over saying "look, here's what seemed interesting to me".

Character with bird (on its head).

The museum was also housing a temporary exhibition - a series of photographs and short films about the Vietnam war. Felt a little abrupt, going from Miro to that, nevertheless fascinating stuff. If you're ever in Barcelona, go see this place. And the Picasso Museum. And maybe Palau Guell. And, if you like sculpture, the Mares collection (free on Sundays). The rest, feel free to take or leave.