Time To Revisit an Old Subject

I've been focused on Russia for the better part of two years, but with the floods in northeast China, there have been many in the Western media who have wondered if the protests in Hebei Province might grow into a revolution. This happens every time China has internal unrest of any kind, but I digress. So in this article, we'll examine the common Western dream of China having a populist revolution and overthrowing the CCP.

So, let's get right down to it.

Of all the reasons to do a deep dive into old historical writings on China, the primary one is to disprove once and for all this notion that responsibility for the country's pervasive ills lies exclusively with the current regime. China apologists are fond of blaming the communists, suggesting in effect that everything was great until these guys showed up."

-Paul Midler, What's Wrong with China, p. 93 (emphasis mine)

We Hear It All the Time

"I feel sorry for the Chinese People, who have to live under the CCP regime."

"Remember, it's not the people of China. It's their oppressive, totalitarian government."

"I hope the People of China will rise up and throw off the shackles of this evil regime."

The internet is filled with this: Westerners, well-intentioned but hopelessly naive, shocked and appalled at the murderous barbarism of the Chinese Communist Party and shaking their heads in sympathy for the people of China, people they see as helpless victims of a government that makes Stalinist Russia on its worst day look tame by comparison. We Westerners seem to have an inborn delusion that any totalitarian nation wants to be just like us but can't because of some dictator who, we are convinced, they want to get rid of. There is a certain longing, an eagerness we might say, for the day when a second Tiananmen Square will happen and this time, led by the great contemporary gods called Social Media, the entire population will throw their fists in the air like Twisted Sister shouting "We're Not Gonna Take It!"

That will be the day, these commentators imagine, when the Chinese population will rise up, throw off the shackles of this Bronze-Age leftover government dressed in Cold War leftover raiment, and declare themselves free and democratic. They then will take their rightful place among a happy, friendly community of well-developed, Democratic nations and join hands with their Western brethren in taking the world into a new and Golden Age. And of course, once the Chinese People, rather than the Party, are in control of their government, all of the PRC's belligerence toward its neighbors, its illegal claims over Tibet and the West Philippine Sea, its genocidal treatment of Uighurs in East Turkestan, its constant bullying of Taiwan, and of course its corruption and piracy, will all cease to exist. "Our enemy is the government, not the People"

...Or so goes the fantasy, anyway.

But unfortunately, just as I already debunked this fantasy about Russia, now I must do likewise to Russia's masters: China. See, the flaw in this entire "we just need to topple the government and the people will be free and be just like us" notion is that it hinges upon two assumptions.

- That this wouldn't be happening without the Party. The assumption is that China's current behavior on the world-stage is something unique in China's history, a momentary blot on the history of an otherwise refined civilization, brought on by the Communist Party, much like the scars on Germany's conscience left by the brief reign of the Nazis.

- That the Chinese People don't want this behavior (and don't want the Party). The assumption is that the Communist Party is something the People of China don't want, an aberration forced on them by a few scheming opportunists who now have their foot on the throat of the helpless, otherwise-liberty-craving Chinese populace.

In this article I will carefully examine the first of these assumptions (and debunk it entirely). The second is more difficult to prove or disprove, but it will be subjected to examination once the first one has been refuted. So let's engage in a little thought exercise, shall we? Let's look at history and see which (if any) of the PRC's barbaric traits is even the slightest bit different from the long line of imperial dynasties before it. Which of China's deplorable behaviors on the world-stage is embedded into the culture of the People themselves, and which ones are a creation of the Party?

Brutally Repressive Totalitarianism

Anyone owning classical books or treatises on philosophy must hand them in within thirty days. After thirty-days anyone found in possession of such writings will be branded on the cheek and sent to work as a laborer on the northern wall or some other government project... Private schools will be forbidden. Those who wish to study law will do so under government officials. Anyone indulging in political or philosophical discussion will be put to death, and his body exposed to the public. Scholars who use examples from antiquity to criticize the present, or who praise early dynasties in order to throw doubt on the policies of our own, most enlightened sovereign, will be executed, they and their families!

-Li Si, "Memorial on the burning of books," quoted de Bary, Chan and Watson 154-155

First of all, the idea of democracy taking root in China at all, even after the Communist Party falls, is exceedingly unlikely considering that the very notion of individual liberty runs counter to millennia of Chinese and Proto-Chinese tradition. As I have mentioned in an earlier article, the first emperor to rule anything that could even be remotely called "China" was the one from whom its Western name is derived: Qin Shihuang. In essence, he created everything China ever was, is, or will be. He established its culture and its very identity. Chinese historian Sima Qian (147 B.C. - 87 B.C) fawningly refers to him as "the First Sovereign Emperor of All Under Heaven (天下)(4)," and Mao Zedong later declared quite plainly in his writings which attempt to pass for poetry, "the Qin Order has survived from age to age (Mosher, 70)."

Case in point: the italicized text above comes from one of the earliest edicts issued by emperor Qin Shihuang. It stated, essentially, that possession of information not sanctioned by the state was punishable by disfigurement and confinement in a forced labor camp. So we can see that neither China's heavy-handed approach to information control and censorship (Horwitz) nor the forced labor camps in Xinjiang (whose existence they deny one minute and justify the next) nor their absolutely murderous response to criticism (Buckley) is anything new. The Communist Party of today is no different from China's first emperor in this regard.

I'm not the first to draw this connection. Not only did Mao himself address such comparisons by saying "we plead guilty" at the Second Plenum of the Eighth Party Congress in 1958 (Mosher, 70), but it must be pointed out that the Qin and Mao regimes were not totalitarian bookends bracketing an otherwise free history. This insistence on controlling the very thoughts of every citizen under their sway, and murderous reprisals for anyone who dared utter a glimmer of independent cognition, have been hallmarks of every emperor in between. The Ming Dynasty was particularly infamous for the casual cruelty of its emperors, especially toward concubines in the imperial residence (Leafe), but the entire history of the country, from Mao to Ming to Han to Qin (the founder of the country) to the proto-Chinese Zhou and Shang dynasties to even the mythical Xia Dynasty (whose very existence is a matter of doubt but which is still recorded in Chinese history books as a proven fact (Lum, pg. 25 & 26; Chu, p. 25)).

Indeed, it has been routinely observed that the entire reason the Chinese were so eager to embrace Leninism (and its East-Asian expansion pack, Maoism) was because it so perfectly fit the autocratic ideals that were already central to their culture (Mosher 70 - 75;). Even China's own academic community proudly declares "the Western institutional arrangement is based on the consideration of decentralization and restrictions on power, In contrast... [in China] the government has always been the only manager." (Yan, p. 21)

Genocidal Aggression Toward Neighbors

Of all the crimes of the current Chinese regime, few have earned as much attention as the endless waves of genocide that have characterized China since the PRC was established. Tibetans, Uighurs, dissidents, the Manchu, the list goes on. Many Westerners have said they are shocked that the Chinese People tolerate such a brutal regime, and they long for the day when the general population will rise up, throw off the Party's yoke, and create a harmonious society where these mass murders are a thing of the past.

The problem with this thinking is that it assumes China was a peaceful and idyllic place before the Communists showed up, and that they are the source of China's brutality. This is patently ludicrous.

Once more Wu Zixu warned, "[Vietnam] is a cancer in our stomach... The Admonition of Pan'geng says, 'An unruly and insolent people should be wiped out, leaving no remnants, no seeds of trouble sown in the land.' This is how the Shang Dynasty prospered." (1)

-Sima Qian, Records of the Historian (Foreign Languages Press edition(2)), p. 435

In the passage above, an official of the Han Dynasty (the dynasty from which the Han Race derives its name; the first dynasty other than the short-lived Qin to actually rule all of what was then considered China) casually suggests slaughtering the entire population of Vietnam (Yueh). "This is how the Shang Dynasty prospered," he says with a shrug, thinking nothing of the murder of several million people. Massacring an entire population is, to him, an inalienable right of the self-styled "Central Nation (more on that later)," to be casually exercised on a whim.

This wasn't a one-off either.

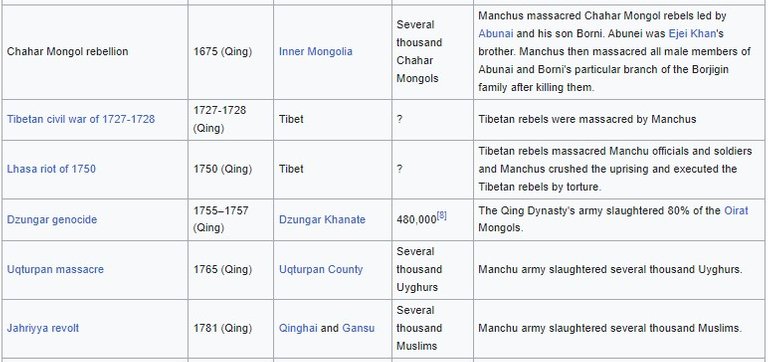

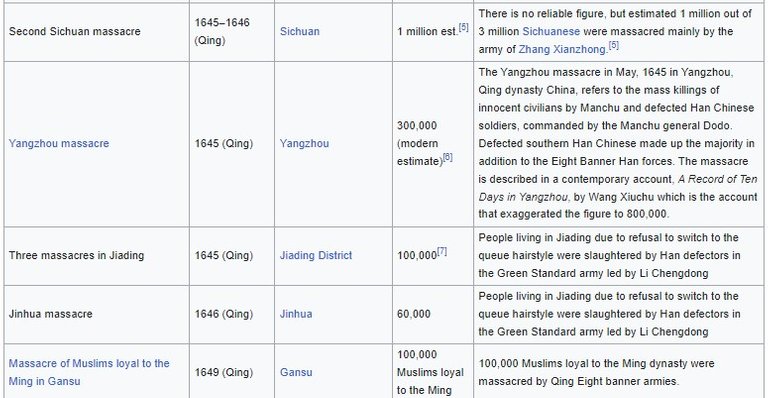

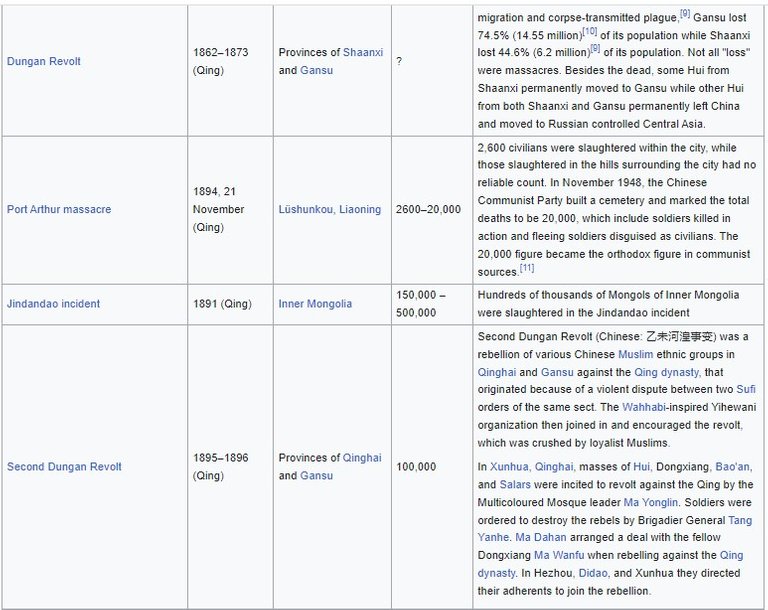

The Qing Dynasty was one of the more murderous of China's dynasties (see photos below). The 1755 Dzungar Massacre, one which is typical of their reign, saw the systematic extermination of the Dzungar Mongols in Xinjiang, China. Led by the Qianlong Emperor, the brutal campaign involved widespread violence and forced relocations, resulting in the near-annihilation of the Dzungar population and a lasting impact on the region's history. The exact number of people killed in the Dzungar Massacre is difficult to determine with precision, but it is estimated that hundreds of thousands to possibly over a million Dzungar Mongols lost their lives as a result of the Qing campaign, which included violence, forced migrations, and other forms of brutality (Seeler).

The Tang, widely considered to be China's most "enlightened" and "civilized" dynasty, were not as known for genocide in Tibet as the Qing and Mao Dynasties were (largely due to the fact that they were a helpless little kingdom cringing fearfully in the shadow of the Tibetan Empire). However, even this dynasty partook in China's favorite national pastime: mass murder. The Guangzhou Merchants Massacre of 878–879 A.D., also known as the "Huang Chao Uprising, was when a Chinese rebel leader slaughtered 200,000 merchants from the Abbasid Caliphate and Persia (Fong). Their crime? They were foreign, and they were rich. Either of those has traditionally been a death penalty offense in China.

And of course, as noted above, this tendency to answer social problems by slaughtering entire populations goes all the way back to the Han Dynasty (who used it because it reminded them of their "Glorious" forebears who did the same thing. The Jie genocide, for example, occurred during the Ran Wei–Later Zhao War in the 4th century, where the Later Zhao state, led by Emperor Shi Hu, conducted a brutal campaign against the Jie people. The conflict led to the near annihilation of the Jie population, with mass killings and forced assimilation. The death toll was estimated at 200,000.

And of course, since it is a foregone conclusion that absolutely every Chinese national (or Western Chinese sympathizer) who reads this will insist that's "hostile Western propaganda," let's see what China's own sources have to say. And in fact, those sources make a point to describe 6 figure massacres with glee any time they speak of China confronting a neighboring tribe or a rebellion. Sima Guang, regarded as the father of modern Chinese historiography, had this to say in his The Road to Unification (translated and transcribed by Stephen W. Mosher in Chapter 2 of Bully of Asia).

During the 34th year of King Zhao of Qin (273 B.C.), General Bai Qi attacked the allied forces of the states of Zhao and Wei at the city of Huayang. Mang Mao, the Wei general, fled the field, while the three generals from Han, Zhao and Wei were captured. Some 130,000 soldiers lost their heads. This was followed by a battle with the forces of General Jia Yan of the state of Zhao, when some 20,000 Zhao soldiers were driven into the river and drowned. During the 43rd year of King Zhao (264 B.C.), General Bai Qi attacked the Han city of Jingcheng, annexing five cities and decapitating some 50,000 heads. During the 45th year of King Zhao (262 B.C.), the state of Qin attacked the state of Zhao at Changping. A ruse led to the surrender of the Zhao army, and the entire force of some 400,000 men was buried alive.

Does anyone still believe that China's penchant for mass murder is something that only the CCP dreamed up? And does anyone believe this side of them will change if the Party falls?

...I rest my case.

Arrogance and Ethnonarcissism

For most of the Han State's history, they have had no contact with other nations except sovereign/vassal relations with those neighboring nations whom they subjugated by means ranging from overt genocide to simply breeding like roaches and starving their neighbors out. The result of this has been a distinct sense that they are the literal center of the universe, a nation not bound by the same rules as all others. This belief is hardwired right into their very name. Look at the etymology of the English word "ethnocentrism" and compare it to the etymology of China's name for itself.

Ethnocentrism \ ETH-nō-SEN-tri-zəm (noun): the attitude that one's own group, ethnicity, or nationality is superior to others; etymology: from "ethnos," meaning "race" or "tribe," "center," meaning exactly what it says, with the suffix "ism" that denotes a philosophy or way of thinking.

中华 \ Zhōng-huá (noun): literally, "flower of the center;" Mandarin word for people of Chinese origin. construction: 中 (zhong) = "center" or "middle," and 华 (hua) meaning "flower" when it stands alone, with other connotations when used in conjunction with other characters. (5)

中国 \ Zhōng-guó (noun): literally, "central nation(6);" Mandarin word for China

It's clear from this that the jingoistic attitude China displays to the world today predates the Communist Party, as it is hardwired right into their name. But just how deep does it run? Well, the truth is Jingoism isn't a by-product of China's apparent success in the past few decades. It's actually the core trait upon which their entire society is based.

From the earliest proto-Chinese tribal attempt to create anything that could remotely be called "civilization," the Han State has derived its entire national identity from the belief that they are the center of the universe. Indeed, their language itself reinforces the mindset that all non-Chinese are mere animals.

"As agricultural society began to acquire a distinct cultural identity and to assume more definite political organization, it began to conceive of itself as distinct from pre-agricultural society. According to one estimate, the Chinese began to think of themselves as "Chinese" (Hua) from about the mid-second millennium [B.C.]... Those excluded, predominantly by cultural criteria, were regarded as 'barbarians.'"

-Smith, Tibetan Nation, p. 80

The biases in the Chinese accounts of foreign countries are obvious. It was assumed that Chinese culture was superior, and therefore all non-Chinese are referred to as “barbarians” who have to be transformed by Chinese civilization. Nomadic peoples are constantly described as having human faces but animal hearts, as being greedy and unrestrained in their behavior, incapable of understanding reason—as “monkeys wearing hats,” or “dwarf-slaves.”

-Pan (2), Son of Heaven and Heavenly Qaghan: Sui-Tang China and its Neighbors, p. 11

China had a very high opinion of its own achievements and had nothing but disdain for other countries. This became a habit and was considered quite natural.

-Sun Zhongshan, Xuanji, vol. 2.

Ancient China was not always in an open state and this self-centered concept was popular in Chinese history.

-Shi Zhongwen & Chen Qiaoshing. China's Culture P.12

Alas, the Chinese people's ethnic and biological cohesiveness has bred a streak of ugly chauvinism in the national character...

-Ben Chu (2), Chinese Whispers, p. 53

As the reader can see, Chinese writing from the Zhou (1050-221 B.C.), Sui (581-618 A.D.) and Tang (618-907) dynasties is riddled with the Nietzschian level of Han-Supremacist rhetoric that many Western China-watchers would like to blame the CCP for. This makes it rather obvious that this is not merely a by-product of the Communist Party or the Xi Regime formed therein, but is in fact a central tenet of China's entire national identity.

The Han thought they were a "Master Race" long before anything resembling Communism ever existed. It's not the Party that made them think this. It's deep-rooted in their culture.

Delusions of a Right to Global Hegemony

The role of the hegemon is firmly embedded in China's national dreamwork, intrinsic to its national identity, and profoundly implicated in its sense of national destiny.

Stephen W. Mosher, Bully of Asia, p. 7 (emphasis mine)

Based on the idea that the Chinese Son of Heaven was to rule All under-Heaven, all foreign states were treated as tributary to China. Their contacts with China were routinely recorded as journeys to pay homage and tribute to the Chinese Son of Heaven, using the rhetoric and vocabulary of the tribute system, and their envoys were made to conform to the rituals required by the tribute system.

-Pan Yihong, Son of Heaven and Heavenly Qaghan, p. 12

The hierarchical principle of the Mandate of Heaven was devised by the early Zhou rulers to justify their conquest of Shang at the end of the second millennium B.C.E. It called for the universal rule of the Son of Heaven over All-under-Heaven (tianxia). “The king leaves nothing and nobody outside his realm” (wangzhe wuwai)

-ibid., p. 19

If anyone thinks that China's belief in their "Heaven-mandated right" to subjugate the world is merely a by-product of the CCP, I have three words for you: Sinocentric Tributary System. China's own literature has insisted that China was the rightful ruler of the world for centuries. There has only been one regime in China's history that has ever abandoned this doctrine, and that was the R.O.C. government. The result?

The result was that the people felt "betrayed" and backed a peasant merchant's son named Mao Zedong, who promised to restore China to what the Han Supremacists called its "rightful place," and all the R.O.C. is left with is the island of Taiwan.

Indeed, the entire reason the Chinese population backed Mao Zedong was his nationalistic, "put China on top" rhetoric. The Communist Party didn't instill this belief in China, they used China's intrinsic egotism to fuel their own rise.

Final Verdict

In many respects, the Party wields its power in a way similar to Chinese emperors of the past... For example, like an emperor in dynastic China who regarded himself as the only legitimate ruler (an individual), the CCP has also perceived itself and is perceived by others as the only ruling party (as an organization) in the country.

-Zheng Yongnian, The Chinese Communist Party as Organizational Emperor, p. 22

Zheng Yongnian, a scholar of Chinese studies at the National University of Singapore, made it plain that there was no meaningful structural difference between the Chinese Imperial system and the Communist Party. And why should there be? The cold reality is that the Communist Party is nothing new. The only thing that has changed is that instead of a hereditary dynasty it is now an oligarchial cabal, so succession is political rather than genetic.

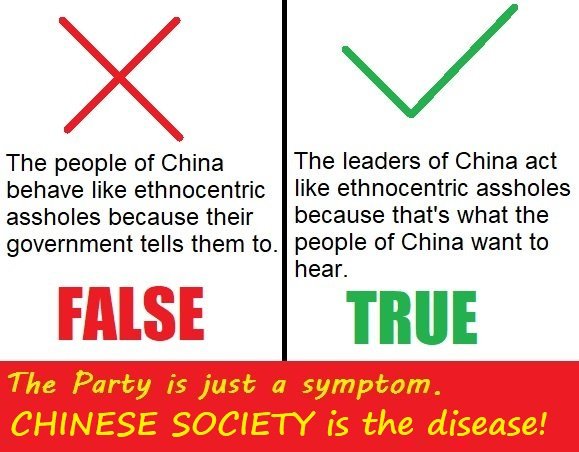

But the Communist Party was put into power by the Chinese specifically because it was exactly what they were used to. The reason why the Party preaches Chinese Exceptionalism is not because they are "using" the People. It's because that's what the People want to hear and the CCP knows they'll be easily disposed of if they don't appeal to that national mythos.

The Chinese did not get aggressive because the CCP wanted them to. The CCP spawned "Wolf Warriors" because that's what the Chinese wanted. They don't slaughter Uighurs and enslave Tibetans in spite of opposition by the People. They do it because that's what the Han People want!

In short, it is not the Party that created China's tyranny and belligerence. It was China's tyranny and belligerence that created the Party. Ergo, westerners who are waiting for the Party to fall and wondering what the People will put in its place, are like someone binge-watching Days of Our Lives reruns waiting (completely in vain) for "the episode where it gets good." No matter what changes, nothing changes.

And make no mistake. If the CCP falls today, the Chinese People will erect a regime every bit as brutal, every bit as aggressive, and every bit as untrustworthy, before lunch tomorrow.

(1) It is a common habit for the Chinese and their apologists to say that any negative news regarding them is "foreign propaganda," and that any citation of their own literature that is used to support anything less-than-praiseworthy about China is "misinterpreted." To this end, I have quoted this call to genocide from the official Chinese translation (by a Chinese-owned, China-based, Chinese-government-founded publisher), of a Chinese history textbook, with its references to an earlier Chinese statesmen. I defy anyone to find any "Western propaganda" there.

(2) It is perhaps worthy of note that both Ben Chu and Pan Yihong are ethnically Chinese themselves, and even they admit this disease of the national character. Ergo, let us dispense with the predictable, trite, and pathetically Goebbels-worthy instinctive go-to response of wumaos and China shills who insist any and all negative coverage of their precious (and of course utterly flawless and Utopian) "Motherland" can have no possible basis other than the supposedly White Supremacist doctrine of what they insist is a jealous and declining West.

(3) The Yang & Yang translation of Records of the Historian, that is, the one from Foreign Languages Press, is BY FAR the more thorough, accurate and complete of the two cited here, while the Wang translation (from China Intercontinental Press) is more like an abridged (though well-translated) collection of highlights. I only cite the Wang translation because I have not finished reading the Yang translation (it's 3 volumes long and was left in a basement in Kharkiv when China's vassal-state, Russia, bombarded the civilians there so I no longer have access to it to finish it and won't until the war is over) and there are certain passages marked in my copy of the Wang translation for which I am unable to properly cite corresponding page numbers in the Yang translation.

(4) Tianxia (天下) is literally translated as "Under Heaven." The words "all" or "everything" are generally added in English translations as context due to Chinese grammar rules which imply that such pairings are universal in their meanings unless otherwise stated. It is interesting to note that this phrase is used in ancient Chinese writings to refer interchangeably to "the Chinese emperor's domain" and "the world." The chain of thought there leads inexorably to an axiomatic assumption that the ruler of China is the ruler of the world, an axiom which is not only instilled into the minds of each and every Chinese citizen past, present or future, but indeed can be proven here to be enshrined right into their language.

(5) In a previous entry I translated this as "Central Race." This is the official translation used by the Chinese government, but it is not the most literal. The origin of the character "华 (hua)" uses strokes designed to invoke flowers, with the implication that something is flourishing in beauty while everything around it is mere weeds. When combined with other characters it is taken as "magnificent" or "splendid (Yabla Chinese)." In the Mandarin language, the shorthand for any word that partially references the Han ethnic group contains this character (Han Trainer Pro), making plain the Chinese view of themselves as "the magnificent splendid flower" of Earth. Meanwhile, Mandarin words that refer to China as a political entity contain the character "中 (zhong)," meaning "central (Yabla Chinese) making China's belief in their own global centrality equally plain.

(6) This name has been used as a nickname for whatever nation held power in the East Asian Plains since long before anything recognizable as "China" ever existed, but it did not become the official name of the nation currently known as "China" until 1911, when it was used as shorthand for 中華民国(Zhonghua Ming Guo), or "Central Race's Republic." When the legitimate Chinese government fell to the Communist rebellion of 1949, the comically misnamed 中華人民共和国 (Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo), or "Central Race's People's Government for the Public Good (officially mistranslated as 'People's Republic of China')" kept the shorthand, since in both cases the first and last characters were "中" and "国."

Works Cited

Buckley, Chris. "Liu Xiaobo, Chinese Dissident Who Won Nobel While Jailed, Dies at 61." New York Times. 13 July, 2017. Web. 14 Feb, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/13/world/asia/liu-xiaobo-dead.html

Chu, Ben. Chinese Whispers. London, 2014. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

ISBN 978-1-7802-2474-9

Fong, Adam. "Ending an Era: The Huang Chao Rebellion of the Late Tang, 874-884." East-West Center. 1 Jan, 2006. Web. 15 Aug, 2023. https://www.eastwestcenter.org/publications/ending-era-huang-chao-rebellion-late-tang-874-884

Horwitz, Josh. "An initiative to “clean up” China’s internet will make it even harder to jump the Great Firewall."

Quartz. 25 Jan, 2017. Web. 14 Feb, 2022. https://qz.com/893238/china-is-cracking-down-on-vpns-making-it-harder-to-jump-the-great-firewall/

Leafe, David. "The Merciless Ming: The Chinese dynasty was unspeakably cruel and one of the most debauched in history - yet they produced the sublime art now on show at the British Museum." Daily Mail. 17 Sep, 2014. Web. 14 Feb, 2022. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2760019/The-Merciless-Ming-The-Chinese-dynasty-unspeakably-cruel-one-debauched-history-produced-sublime-art-British-Museum.html

Li Si, "Memorial on the burning of books," Shi Ji87:6b-7a, translated in Theodore de Bary, Wingstit Chan & Burton Watson, eds., Sources of the Chinese Tradition. New York, 1960. Columbia University Press.

ISBN 978-0-23108-602-8

Lum, Peter. The Growth of Civilization in East Asia: China, Japan and Korea to the 14th Century'. New York, 1969. S. G. Phillips.

SBN 87599-144-0 (No ISBN)

Midler, Paul. What's Wrong with China. Hoboken, 2018. Wiley

ISBN 978-1-119-21371-0

Mosher, Stephen W. Bully of Asia. Washington, 2017. Regnery.

ISBN 978-1-62157-696-9

Pan Yihong. Son of Heaven and Heavenly Qaghan: Sui-Tang China and Its Neighbors. Bellingham: Center for East Asian Studies, Western Washington University, 1997.

ISBN 978-0914-5842-09

Seeler, Jonathan. "The Dzungar Genocide." Sutori.com. Web. 15 Aug, 2023. https://www.sutori.com/en/story/the-dzungar-genocide--PtuVvoJbMPgy1K4t5k1KhcDe

Sevin Nguyen. "A Brief History of Vietnam: The 4 Periods of Chinese Domination." Medium.com. 15 Feb, 2018. Web. 11 Feb, 2022. https://medium.com/@sushisev/the-rich-history-of-vietnam-the-4-periods-of-chinese-domination-16acbf426071

Sima Qian. Trans. Wang Guozhen. Records of the Historian. Beijing, 2017. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-7-5085-3050-5

Sima Qian. Trans. Yang Xianyi & Yang, Gladys. Records of the Historian. Beijing, 2010. Foreign Languages Press.

ISBN 978-7-119-05090-4

Shi Zhongwen & Chen Qiaosheng. Trans. Wang Guozheng. China's Culture. Beijing, 2010. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-7-5085-1298-3

Smith, Warren W. Tibetan Nation - A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations. Boulder, 1996. Westview.

ISBN 978-0-813-332-802

.

Yan Jirong. Trans. Huang Fang. China's Governance. Beijing, 2017. China Renmin University Press.

ISBN 978-7-300-24625-3

Zheng Yongnian. The Chinese Communist Party as Organizational Emperor. New York, 2010. Routledge.

ISBN 978-0415559652

Zhongshan, Sun (孙中山). “Zhongguo wenti de zhen jiejue-Xiang Meiguo renmin de huyu” 中国问题的真解决—向美国人民的呼 (The true solution of Chinese question: An appeal to the people of the United States). In: Department of CCP History, Renmin University of China ed. Zhongguo jindai zhengzhi sixiangshi cankao ziliao 中国近代政治思想史参考资料 (Sources materials of modern Chinese political thought), 1980, Vol.2.

"华 - huá Definition." Yabla Chinese English Pinyin Dictionary. Web, 9 Nov, 2019. https://chinese.yabla.com/chinese-english-pinyin-dictionary.php?define=hua

"中- zhōng Definition." Yabla Chinese English Pinyin Dictionary. Web, 9 Nov, 2019. https://chinese.yabla.com/chinese-english-pinyin-dictionary.php?define=zhong