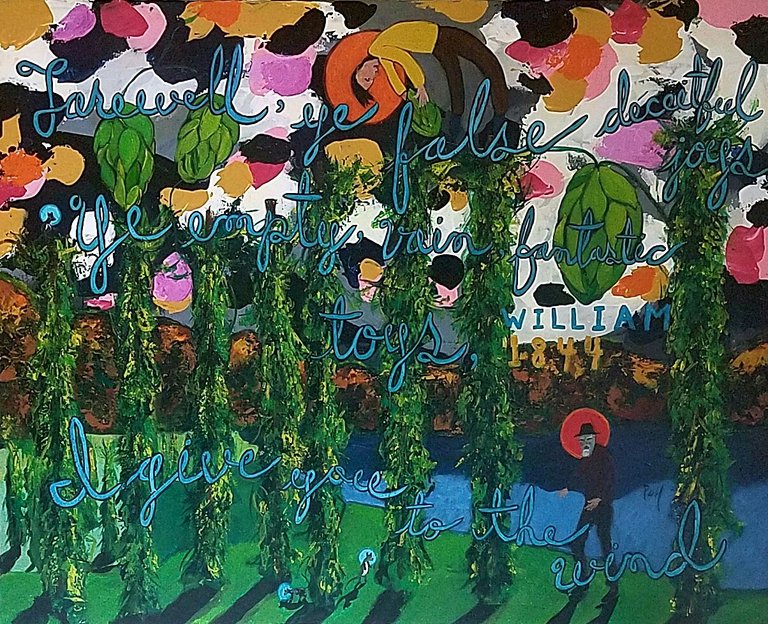

William the Hops Farmer 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 30 x 24"

Hops farmer William Huntington Throop (1807 - 1883), had great faith in science. Especially the developing social sciences. He attended several meetings on Fourierism in the mid-1840s. This was a French socialist movement to build off the philosophy of Charles Fourier (died 1837). Karl Marx would term Fourierism derogatively in his writing, calling it “utopian socialist” and unreachable. Still, Fourier had views about human equality that were way ahead of his time. He coined the term “feminism”, and advocated for sexual rights, believing people changed preferences and behaviors during a lifetime. Homosexuality and adrogyny were normal, and all sexual expression should be tolerated as long as no one gets abused. Furthermore, he believed that “affirming one’s difference” can actually be a benefit to communities.

His underlying hope was to obtain a great socialist society working in harmony to provide mutual aid to its members.

Wow. My Central New York farmer ancestor was a socialist. And he wasn’t alone!

That is something the history books for kids and college students never mention while fawning over Presidents with slaves in hero worshiping detail. Free market capitalism (regulated by and for the powder-wigged white men) is the American economic system lauded in high school history books. It was those unwashed hordes of southern and eastern European immigrants arriving in the late 18th century who spread dangerous socialist ideas about communal living.

Instead of popular social movements gathering converts in early America, the textbooks focus on religious revivalism, with traveling preachers and week-long retreats about God in heaven and angels of mercy. Mid-nineteenth century Central NY is known as the “Burned-over District”, which was actually a sarcastic term coined by a preacher of the Second Great Awakening, Charles Finney, to explain the inhabitant’s skepticism of established religion.

It was reported as having been a very extravagant excitement (early wave of Second Great Awakening); and resulted in a reaction so extensive and profound, as to leave the impression on many minds that religion was a mere delusion. A great many men seemed to be settled in that conviction. Taking what they had seen as a specimen of a revival of religion, they felt justified in opposing anything looking toward the promoting of a revival.

Before antibiotics, mortal fears were triggered with the onset of the common cold. Coping was always a religious exercise. Yet thinking people had to question why God would take the best and the brightest just because one might cut his toe on a sharp stone. Religion just wasn’t good enough anymore, not after steamboats and locomotives came into vogue. Even the Lord’s ministers and messengers suffered profoundly their sins. God was real, and God made man, but he didn’t make man to stand there waiting and stupid, like a beast of burden. Socialism was a viable political philosophy stemming from Christianity. New testament stories of Jesus promised heaven to believers, but believers didn’t want their babies to die on a savior’s whim. People, like crops, should not be left to chance. The quest for knowledge was insatiable. Science was praised because there was a lot of good news coming out of it. Discoveries in every field of human endeavor that would improve the quality of life in a generation. Good stuff for families that God was unable to deliver after several thousand years.

Eugene Throop, William and Calphurnia’s fourth child, died a toddler in 1843. The family was hungry for practical ideas. Fourierism would take care of those who suffer. Rugged individualism was fine for young men striking out on their own, but families needed help when crisis came. Socialist philosophy would certainly please God—it claimed to do what Jesus wanted them to do—that is, take good care of each other. Perhaps a collective concerned with the health and contentment of all its neighbors would make the Lord rethink his cruel abduction of their innocent children.

William wrote about Fourierism to his brother George a few months after his little boy Eugene died:

Preston, Chenango County, N.Y.

East Hamilton (New York), Dec. 3, 1843

Brother George:

I sit down to inform you of a meeting of the directors of the Hamilton Fourier Association, which will take place on the 9th inst. at our place. We shall expect you to be there. Almira, too, wants to be under the doctor’s care one week more. As to her eyes, she cannot say. I can say, though, I think they are better. The doctor thinks there is no doubt but that he can cure them.

We had a Fourier meeting last Thursday evening, called the best we have had. I regret much that my friends could not all be there. A feeling of unbounded sympathy for human want and suffering seemed to pervade the whole audience, and when Mr. Cook impressed upon the meeting the importance of a Home Association and the misery and unhappiness attending the breaking up of households, children and parents, brothers and sisters scattered to the four corners of the earth, in many instances never expecting again to grasp the warm kindred hand of love or hear the soothing voice of friendship from those so near and dear to them, it touched a kindred chord that vibrated in every heart alike.

That the social feelings are not enough attended to I think is evident. Whether Association will cure the evil, we have yet to find out by trying it. That it will, I have my reasons to say yes. At all events, it is best to try it. If it succeeds, O, happy era; better, far better, to me than any heaven all the priests have ever told me about; a heaven of equality to all, the good, rich and poor, bond and free.

If there is anything that will purify human nature it will be such a state of society as that.

Are not the signs of the times ominous of good to the mass? Look to Ireland. What do we see? An O’Connel, who said years ago that English gold could not buy him as it had so many so-called great men before him. No; he stands the noble champion of human rights, especially to his oppressed countrymen, wearing out his life in raising up his degraded and downtrodden brethren. If you have read his last address to the people of Ireland, you will say with me: “Go forward, noble son of the Emerald Isle. Every freeman and philantropist under heaven will second your efforts.”

Did you read what the worthy John Q. Adams said to the abolitionists who asked him to address them? If you have, say with me: “Worthy, venerable patriot of almost a century, we hope your last days may be your best days, and if you do not live to see slavery abolished in America, we hope to.” Yes, and to have a hand in it too; not by force, but by the more powerful weapon of justice and the exercise of the law of kindness.

Why, the whole world is in commotion, and it seems all tending to one grand center, viz.: the upraising of the oppressed and the advancement of correct liberal principles. The people are determined to make a trial and a thorough one, to see if they can form an Association here. We had at our last meeting to speak to us the perservering, go-ahead Mr. Cook; the faithful, upright Mr. Stebbins; the eccentric, but humanity-loving Mr. Hatch; the blunt, honest Mr. Hart. They all seemed to feel right, and, of course, spoke to the point. I hope to hear something from yourself and DeWitt and others at our next, which will be on the evening of the 9th inst., the same day as the directors meet. No more.

William

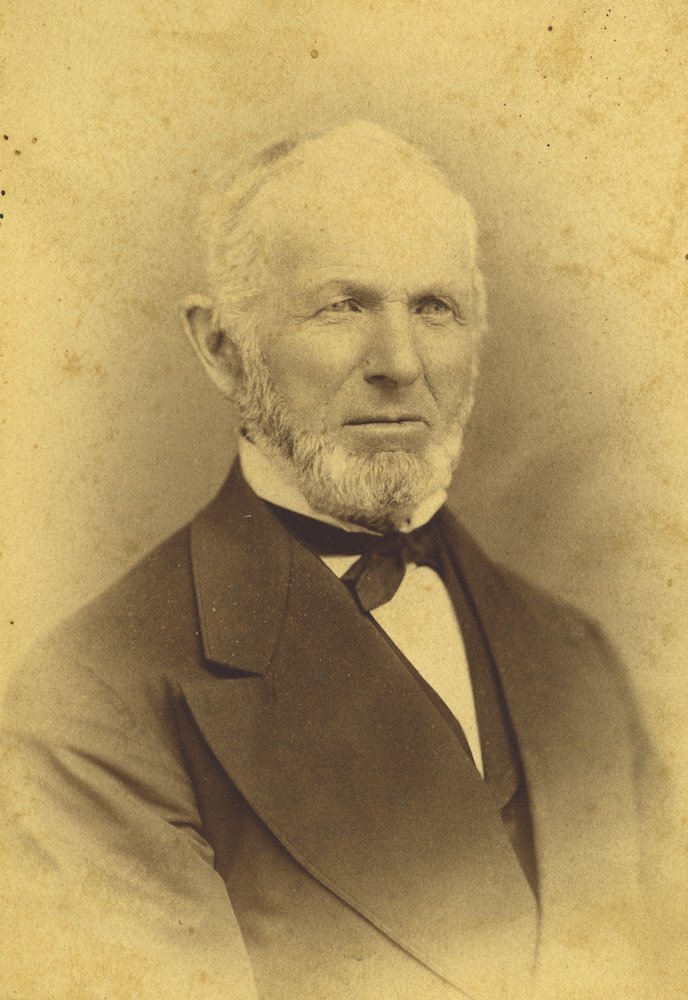

William Throop circa 1875